Mar 25, 2024

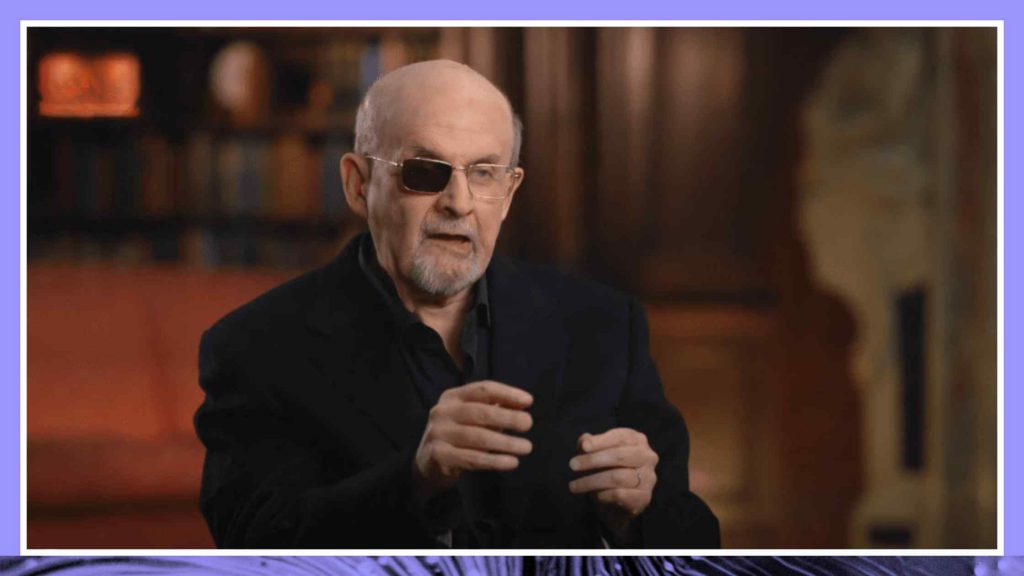

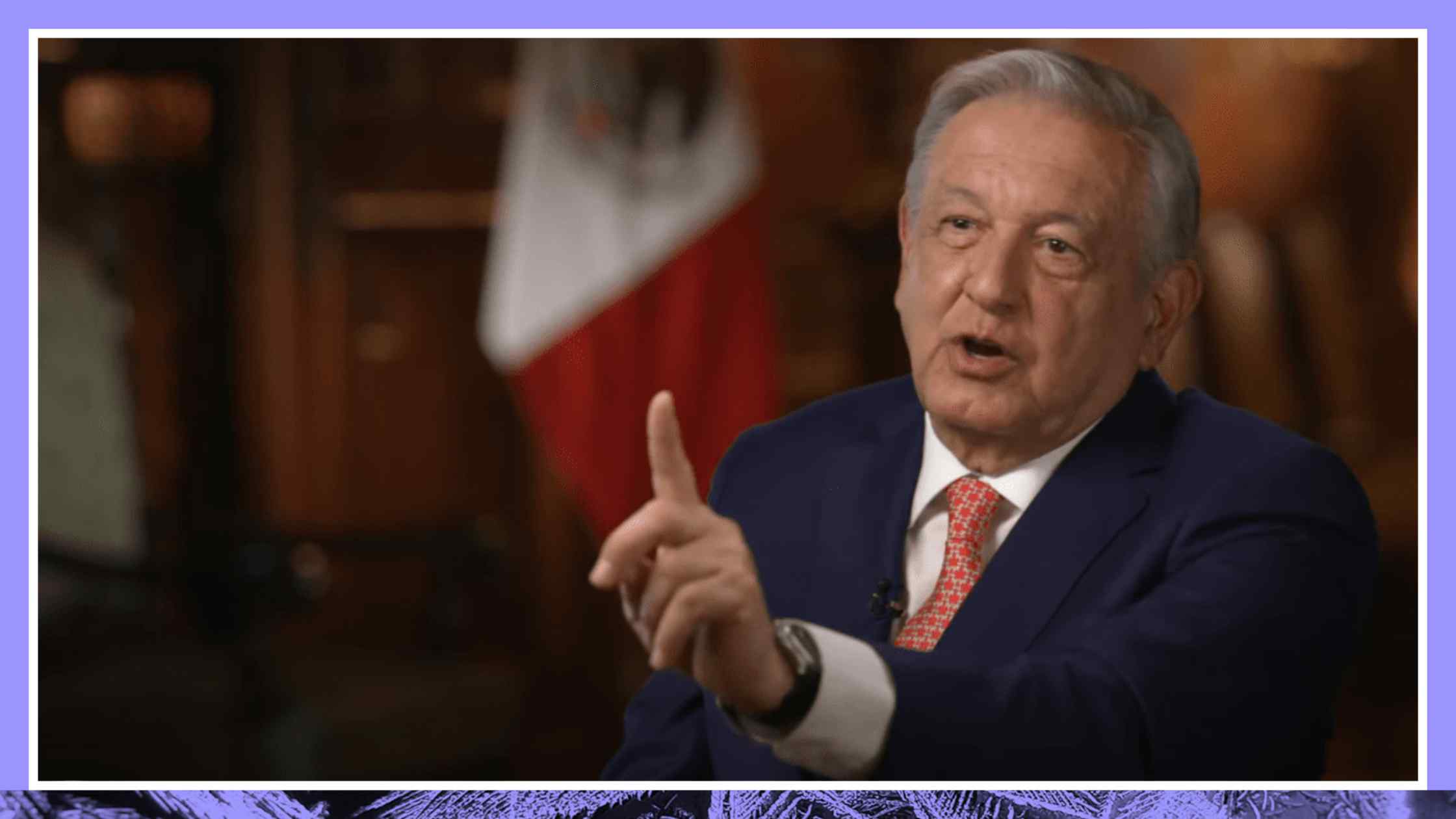

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador Interview

Mexican President talks about his handling of the border, Mexican drug cartels, fentanyl, and the Mexico-U.S. relationship. Read the transcript here.

Sharyn Alfonsi (00:01):

Immigration, the border and the economy have emerged as key issues in this year’s presidential election and may determine who wins the White House, but the person who could tip the scales for either candidate is another President, Mexico’s President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, widely known by his initials, AMLO. Charismatic, and often combative, AMLO won a landslide victory in 2018 on the promise to root out corruption, reduce poverty and violent crime. Now, 70 years old, and in the final stretch of his term, we met the president in Mexico City for a candid conversation about his handling of immigration, trade, the fentanyl crisis, and the cartels. He told us why he thinks when Donald Trump says he’s going to shut down the border or build a wall, he’s bluffing.

Speaker 2 (00:55):

The story will continue in a moment.

Sharyn Alfonsi (01:01):

President Trump is saying he wants to build a wall again.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (01:04):

On the campaign.

Sharyn Alfonsi (01:06):

But you don’t think he’d actually do it because-

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (01:08):

No.

Sharyn Alfonsi (01:08):

Because he needs Mexico.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (01:11):

Because we understood each other very well. We signed an economic, a commercial agreement that has been favorable for both nations. He knows it and President Biden the same.

Sharyn Alfonsi (01:23):

What about the people that’ll say, “Oh, but the wall works,”?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (01:26):

It doesn’t work.

Sharyn Alfonsi (01:28):

President López Obrador says he told that to then President Trump during a phone call, they were supposed to be discussing the pandemic.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (01:36):

It was an agreement not to speak about the wall because we were not going to agree.

Sharyn Alfonsi (01:42):

Then you talked about it.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (01:43):

That was the only time, and I told him, “I’m going to send you, Mr. President, some videos of tunnels from Tijuana up to San Diego that pass right under US Customs. He stayed quiet and then he started laughing and told me, “I can’t win with you.”

Sharyn Alfonsi (02:03):

We met President Andrés Manuel López Obrador at Mexico’s National Palace earlier this month with six months left on his six-year term López Obrador’s power in Mexico and influence in the United States has never been greater. The White House witnessed it here last December, when a record 250,000 migrants overwhelmed the US southern border with Mexico. President Biden called you. He sent his Secretary of State. What did they say to you and what did they ask for from you?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (02:36):

For us to try and contain the flow of migration.

Sharyn Alfonsi (02:40):

A month later, US Customs and Border Patrol reported the number of migrant crossings dropped by 50%. What did you do between December and January that changed that number so dramatically?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (02:55):

We were more careful about our southern border. We spoke with the presidents of Central America, with the president of Venezuela and with the president of Cuba. We asked them for help in curbing the flow of migrants. However, that is a short-term solution, not a long-term one.

Sharyn Alfonsi (03:12):

Mexico also increased patrols at the border flying some migrants to the southern part of Mexico and deporting others. But by February, the number of migrants crossing into the US began to rise again, and the Border Patrol expects a sharp increase in that number this spring. Everybody thinks you have the power in this moment to slow down migration. Do you plan to?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (03:37):

We do, and want to continue doing it, but we do want for the root causes to be attended to, for them to be seriously looked at.

Sharyn Alfonsi (03:47):

With the ear of the White House, President Lopez Obrador proposed his fix, that the United States commit $20 billion a year to poor countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, lift sanctions on Venezuela, and the Cuban embargo and legalize millions of law-abiding Mexicans living in the U.S. If they don’t do the things that you’ve said need to be done, then what?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (04:12):

The flow of migrants will continue.

Sharyn Alfonsi (04:17):

Your critics have said what you are doing or what you are asking for to help secure the border is diplomatic blackmail. What do you say?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (04:25):

I’m speaking frankly, we have to say things as they are, and I always say what I feel. I always say what I think.

Sharyn Alfonsi (04:34):

If they don’t do those things, will you continue to help to secure the border?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (04:39):

Yes, because our relationship is very important. It is fundamental.

Sharyn Alfonsi (04:49):

For much of the last six years, President Lopez Obrador has held a televised seven A.M. press conference five days a week. During our visit, he was dissecting fake news. The briefing lasted more than two hours. Is it a pulpit or is it a press conference?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (05:06):

It is a circular dialogue, even though my opponents say that I’m on a pulpit.

Sharyn Alfonsi (05:13):

Time is the only luxury AMLO seems comfortable spending. When he took office, he sold the presidential jet and his predecessor’s fleet of bulletproof cars in favor of his Volkswagen. He uses his daily briefings to rail against the elite and enemies, real and perceived. At times it can feel like a political telenovela. At a briefing last month, the President stunned the audience when he read the cell phone number of a New York Times reporter who was pursuing what he viewed as a critical story of him. It looks like you were threatening that reporter.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (05:49):

I didn’t do it with the intention of harming her. She, like yourself, are public figures and I am as well.

Sharyn Alfonsi (05:57):

But this is a dangerous place for reporters and you know that threats often come in texts and phones when you put her phone number up behind you, you realize what you were doing.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (06:08):

No, no, no, no.

Sharyn Alfonsi (06:09):

But what did you think you were doing?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (06:12):

It’s a form of responding to a libel. Imagine what it means for this reporter to write that the president of Mexico has connections with drug traffickers and without having any proof, that’s a vile slander.

Sharyn Alfonsi (06:27):

Then why not just say it’s not true?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (06:29):

Because libel, when it doesn’t stain, it smears.

Sharyn Alfonsi (06:33):

López Obrador’s bare-knuckle brawls with the press are in sharp contrast to the softer approach he’s taken with drug cartels. He dissolved the federal police and created a national guard to take over public security, and he invested millions to create jobs for young people to escape the grip of the cartels. According to the Mexican government homicides have dropped almost 20% since he took office. The President calls his approach hugs, not bullets. How is that working out for Mexico?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (07:05):

Very well.

Sharyn Alfonsi (07:06):

There are still 30,000 homicides in Mexico and very few of those are prosecuted. There’s an idea that there’s still lawlessness in Mexico. Is that fair?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (07:18):

Of course, we prosecute them. There’s no impunity in Mexico. They all get prosecuted.

Sharyn Alfonsi (07:23):

It’s a small percent.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (07:26):

More than before.

Sharyn Alfonsi (07:27):

According to Mexico Evalua, a Mexican think tank, about 5% of the country’s homicides are prosecuted and a study last year reported cartels have expanded their reach, employing an estimated 175,000 people to extort businesses and traffic migrants and drugs into the U.S. Can you reach the cartel and say, “Knock it off,”?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (07:50):

No, no, no, no. What you have to do with the criminals is apply the law, but I’m not going to establish contact, communication with a criminal, the president of Mexico.

Sharyn Alfonsi (08:01):

Are you saying you don’t have to reach out to them or communicate with them?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (08:04):

No, no, no, no. It because you cannot negotiate with criminals.

Sharyn Alfonsi (08:09):

The head of the DEA says cartels are mass-producing fentanyl, and the US State Department has said that most of it is coming out of Mexico. Are they wrong?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (08:20):

Yes. No, or rather they don’t have all the information because fentanyl is also produced in the United States.

Sharyn Alfonsi (08:29):

The State Department says most of it’s coming from Mexico.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (08:32):

Fentanyl is produced in the United States, in Canada and in Mexico, and the chemical precursors come from Asia. You know why we don’t have the drug consumption that you have in the United States? Because we have customs traditions and we don’t have the problem of the disintegration of the family.

Sharyn Alfonsi (08:53):

But there is drug consumption in Mexico.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (08:56):

But very little.

Sharyn Alfonsi (08:57):

Why the violence then, in Mexico?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (09:00):

Because drug trafficking exists, but not the consumption.

Sharyn Alfonsi (09:06):

López Obrador says threats by US lawmakers to shut down the border to curb drug trafficking is little more than saber-rattling. That’s because last year Mexico became America’s top trading partner.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (09:20):

They could say, “We are going to close the border,” but we mutually need each other.

Sharyn Alfonsi (09:25):

What would happen to the US if they closed the border?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (09:27):

You would not be able to buy inexpensive cars if the border is closed. That is, you would have to pay 10,000, $15,000 more for a car. There are factories in Mexico and there are factories in the United States that are fundamental for all the consumers in the United States and all the consumers in Mexico.

Sharyn Alfonsi (09:51):

Last year, the Mexican economy grew 3% and unemployment hit a record low. But critics say Mexico’s economic growth isn’t because of the president, rather, in spite of him. López Obrador directed billions to signature mega projects like an oil refinery in his home state and a railroad through the Yucatan jungle costing an estimated $28 billion. What about infrastructure? Aren’t there more dire concerns like clean water, roads, reliable energy when you’re trying to attract business to Mexico?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (10:26):

We’re doing both fixing the roads and building this train. It will link all the ancient Mayan cities and is going to allow Mexicans and tourists to enjoy a paradise region that is the southeast of Mexico.

Sharyn Alfonsi (10:43):

López Obrador has spent unapologetically on social programs, doubling the minimum wage, increasing pensions and scholarships. His approval rating has remained high, upwards of 60% for most of his presidency. Your critics say that you’re popular because you give people money. What do you say?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (11:04):

I would say they’re partly right. Our formula is simple. It is not to allow corruption, not to make for an ostentatious government for luxuries and everything we save, we allocate to the people.

Sharyn Alfonsi (11:19):

Do you think that you’ve been able to get rid of the corruption in Mexico?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (11:24):

Yes.

Sharyn Alfonsi (11:24):

Completely?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (11:27):

Yes. Basically, because corruption in Mexico started from the top down.

Sharyn Alfonsi (11:33):

The Transparency International reports no improvement in the corruption problems that have plagued Mexico for decades. Huge crowds gathered last month, accusing the president of trying to eliminate the country’s democratic checks and balances. In June, Mexico will have one of the largest elections in its history. In addition to the presidency, 20,000 local positions are up for grabs. The cartels have funded and preyed on local candidates. Last month, two mayoral hopefuls were killed within hours of each other, raising fears of a bloody election.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (12:09):

I can travel throughout the entire country without a problem. There is no region that I cannot go and visit.

Sharyn Alfonsi (12:15):

The number of government officials and candidates murdered rose from 94 in 2018 to 355 last year. You don’t view that as a threat to you, obviously, but do you view it as a threat to democracy?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (12:29):

No. There are some specific instances. There is no state repression.

Sharyn Alfonsi (12:35):

But if a candidate’s afraid to run because they may be assassinated, isn’t that a threat to democracy?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (12:43):

Generally, they all participate. There are many candidates from all the parties.

Sharyn Alfonsi (12:48):

His hand-picked successor, Claudia Scheinbaum, has a commanding lead in the polls and could become Mexico’s first female president. Lopez Obrador told us when he leaves office, he will retire from politics and write books. But what he does next at the border or doesn’t do could shape the next chapter of the United States.

Transcribe Your Own Content

Try Rev and save time transcribing, captioning, and subtitling.