Rev’s Transcript Library

Explore our extensive collection of free transcripts from political figures and public events. Journalists, students, researchers, and the general public can explore transcripts of speeches, debates, congressional hearings, press conferences, interviews, podcasts, and more.

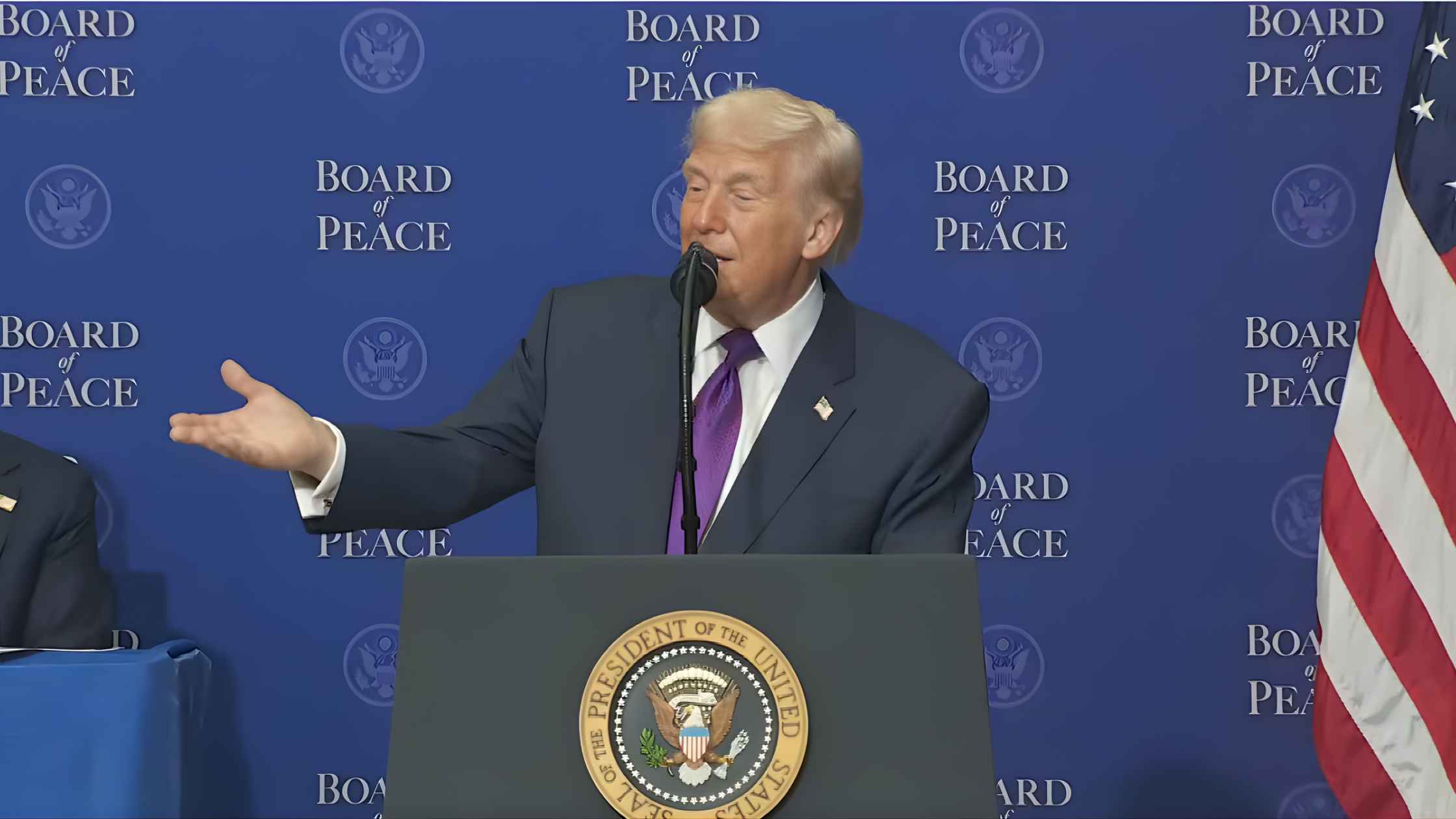

First Board of Peace Meeting

World leaders gather for Donald Trump’s inaugural Board of Peace meeting. Read the transcript here.

Avalanche Update Press Conference

Nevada County Sheriff's office holds a news briefing following the avalanche in California's Sierra Nevada mountains. Read the transcript here.

White House Black History Month Event

The White House holds an event to honor the 100th anniversary of Black History Month. Read the transcript here.

Family of Jesse Jackson Press Conference

The family of the late civil rights leader Reverend Jesse Jackson holds a news conference in Chicago. Read the transcript here.

Karoline Leavitt White House Press Briefing on 2/18/26

Karoline Leavitt holds the White House Press Briefing for 2/18/26. Read the transcript here.

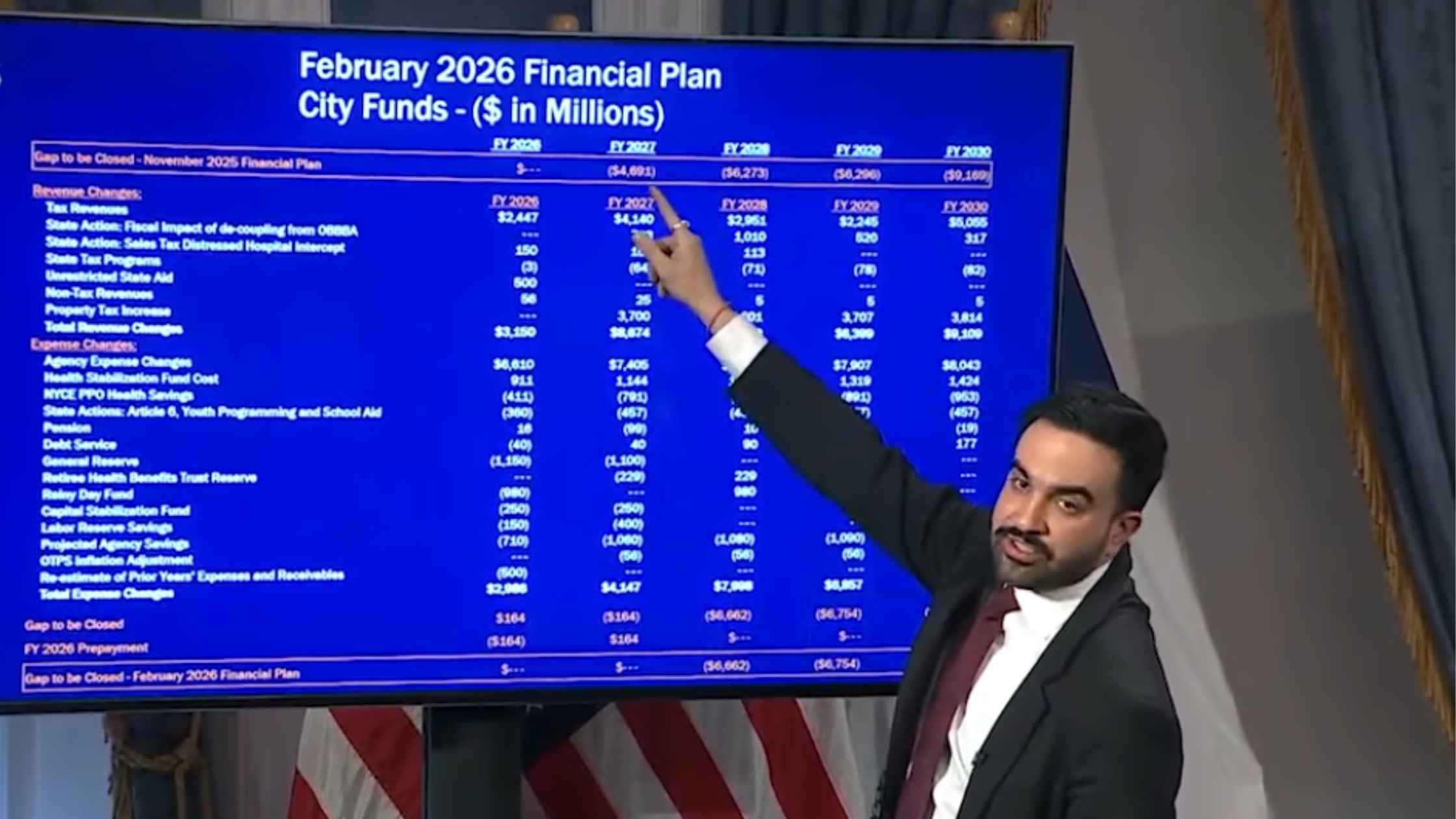

NYC Preliminary Fiscal Year 2027 Budget

New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani holds a press briefing to unveil the preliminary fiscal year 2027 budget for the city. Read the transcript here.

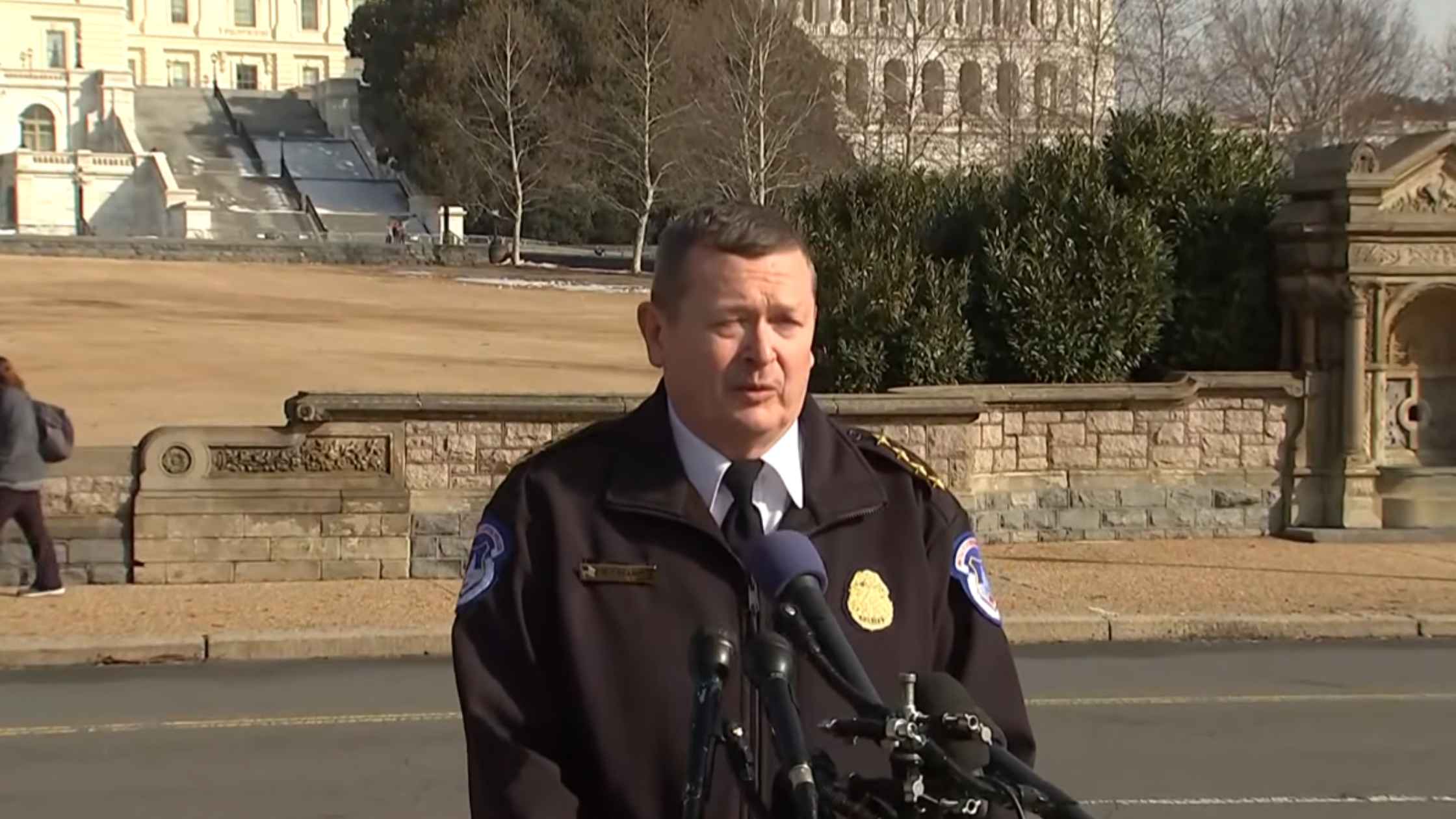

Armed Suspect Arrested at Capitol

USCP Chief Michael Sullivan briefs the press after officers arrest an 18-year-old suspect with a loaded shotgun near the Capitol. Read the transcript here.

DeSantis Holds Workforce Education Briefing

Ron DeSantis holds a press briefing to celebrate Florida ranking #1 in workforce education. Read the transcript here.

Al Sharpton Eulogizes Jesse Jackson

The Reverend Al Sharpton holds a press conference after the announcement of Reverend Jesse Jackson's death. Read the transcript here.

Subscribe to The Rev Blog

Sign up to get Rev content delivered straight to your inbox.