Rev’s Transcript Library

Explore our extensive collection of free transcripts from political figures and public events. Journalists, students, researchers, and the general public can explore transcripts of speeches, debates, congressional hearings, press conferences, interviews, podcasts, and more.

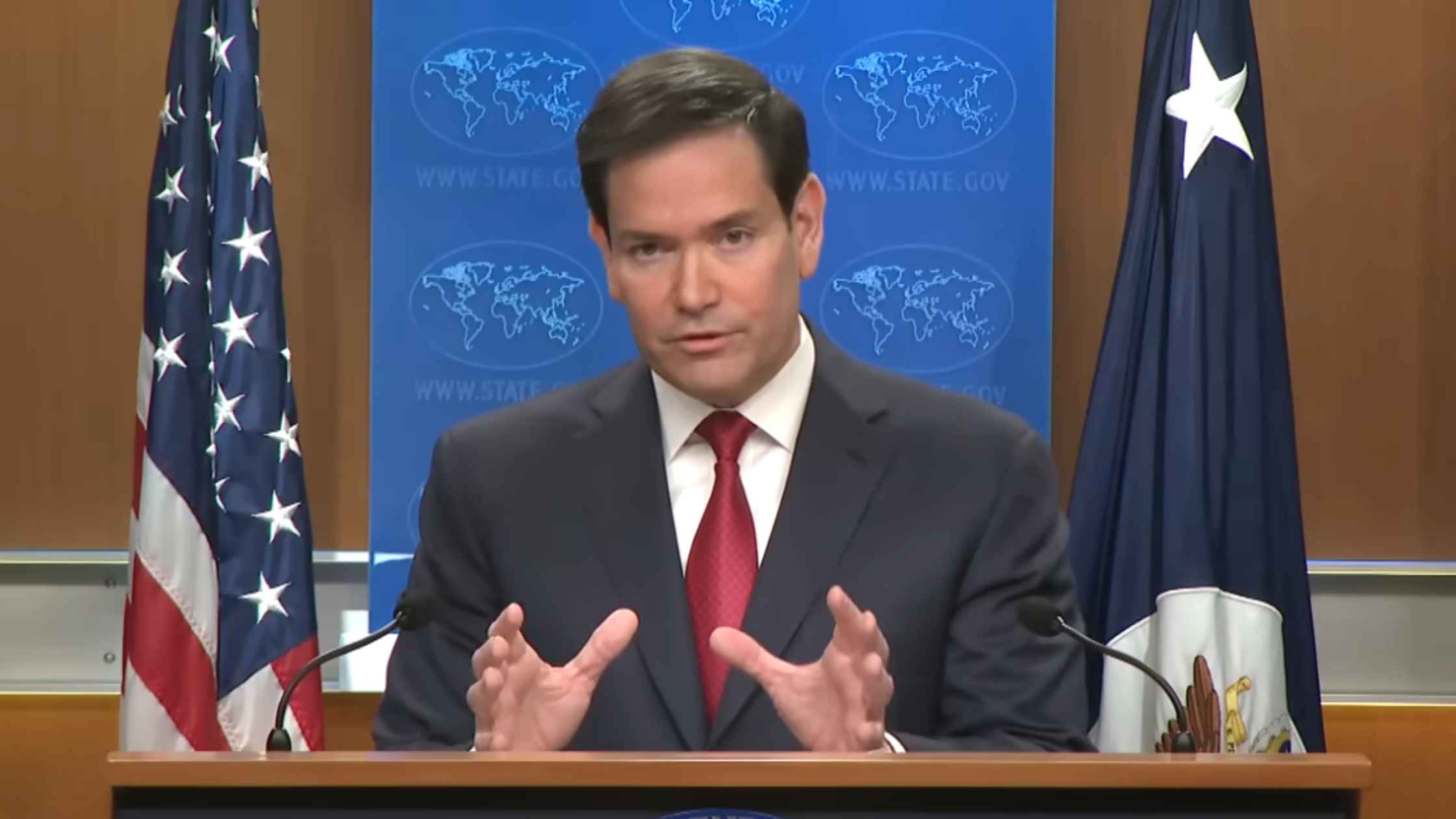

State Department Year End Press Conference

Marco Rubio holds a year-end news conference on Venezuela, the Ukraine War, and Gaza. Read the transcript here.

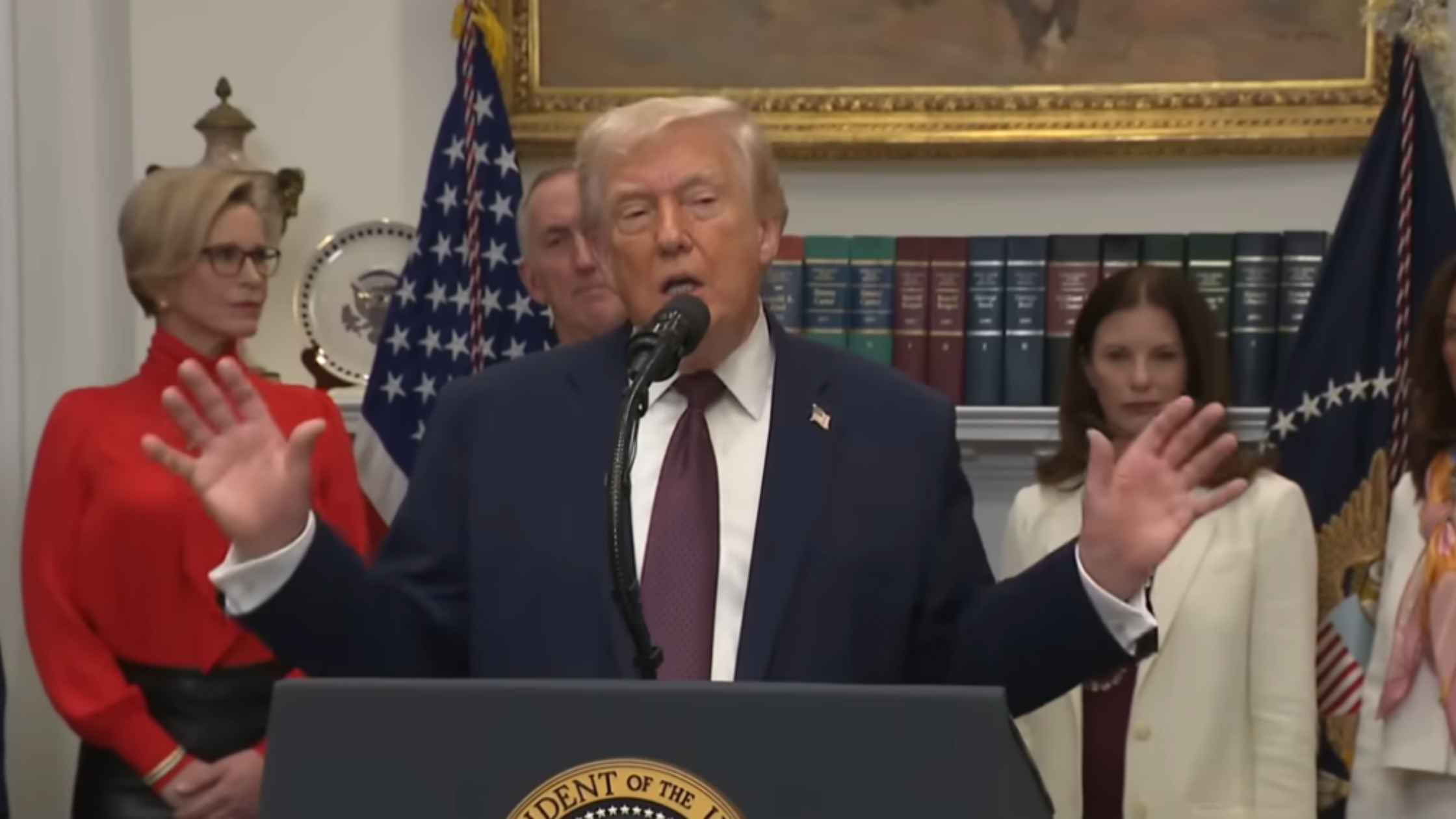

White House Announces Lower Drug Prices

Donald Trump announces "most favored nation" pricing on prescription drugs with major pharmaceutical companies. Read the transcript here.

Joshua vs Paul Post Fight Press Conference

Anthony Joshua vs Jake Paul post-fight press conference. Read the transcript here.

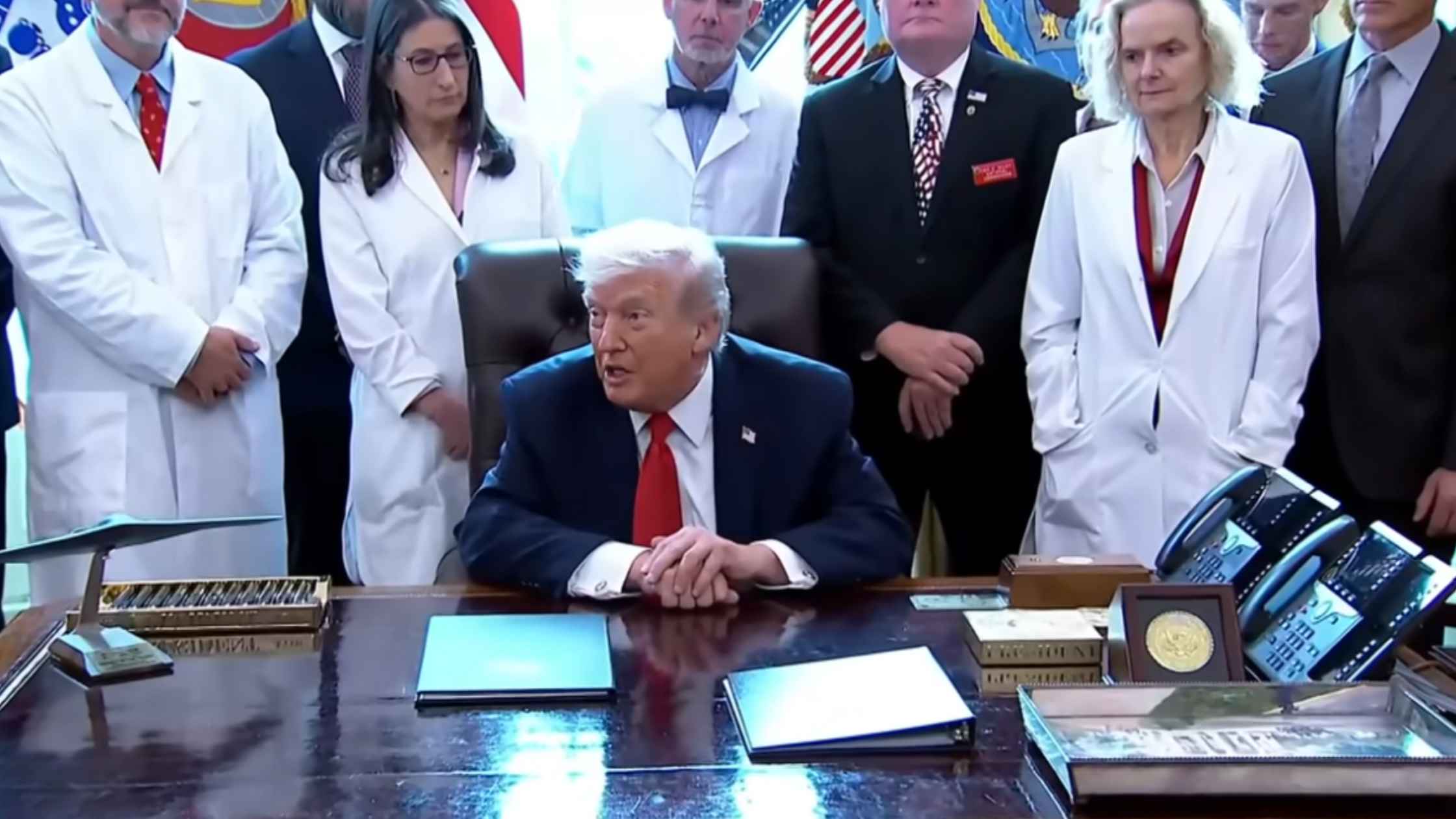

Marijuanna Reclassification

Donald Trump orders the reclassification of marijuana, downgrading it to a Schedule III drug. Read the transcript here.

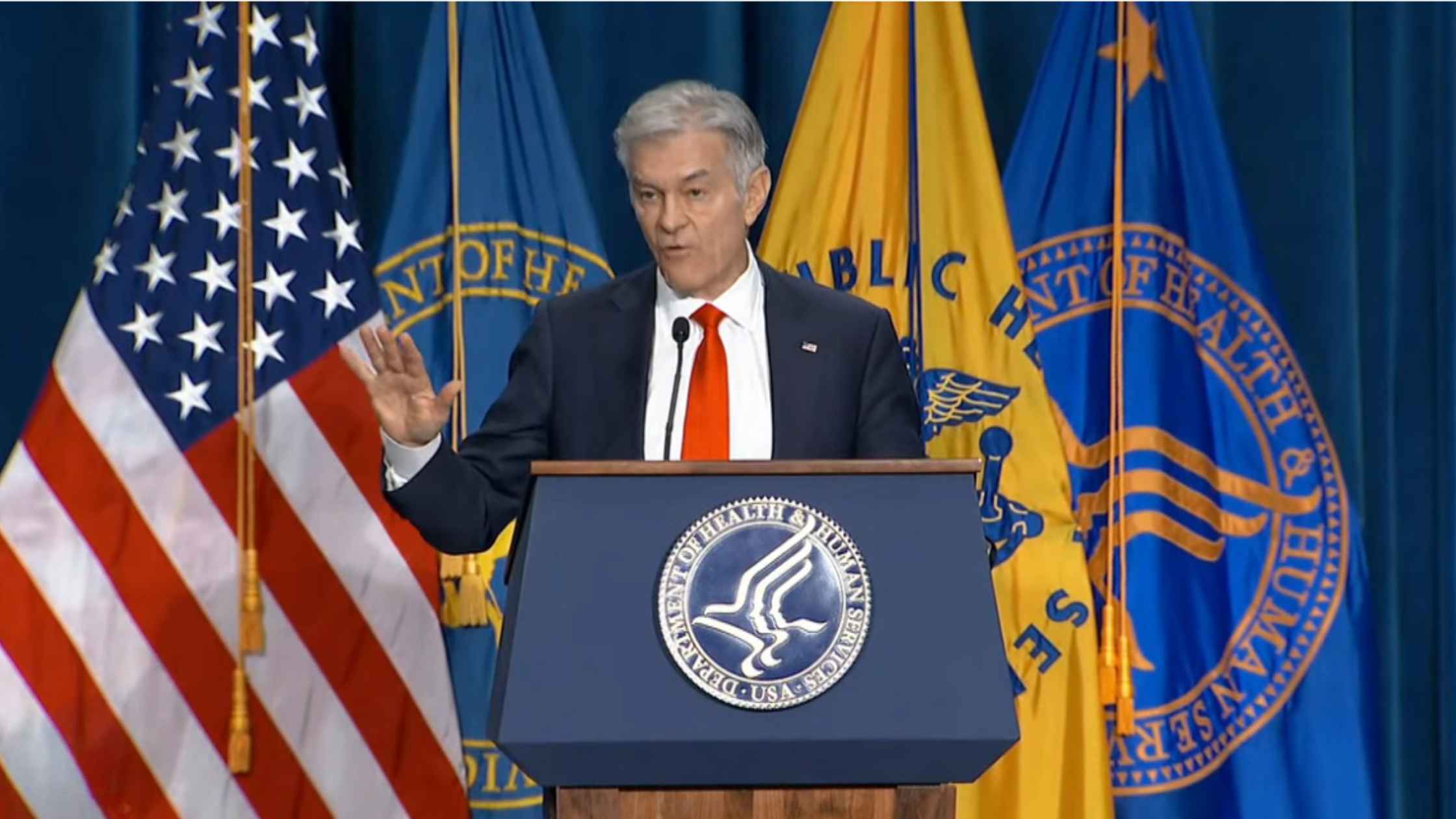

Restrictions On Gender-Affirming Care For Minors

Health Secretary RFK Jr. and Dr. Oz unveil new restrictions on gender identity care for minors. Read the transcript here.

Hearing on Artificial Intelligence

House Homeland Security Committee hearing on artificial intelligence. Read the transcript here.

FCC Oversight Hearing

Senate FCC oversight hearing with FCC chair Brendan Carr. Read the transcript here.

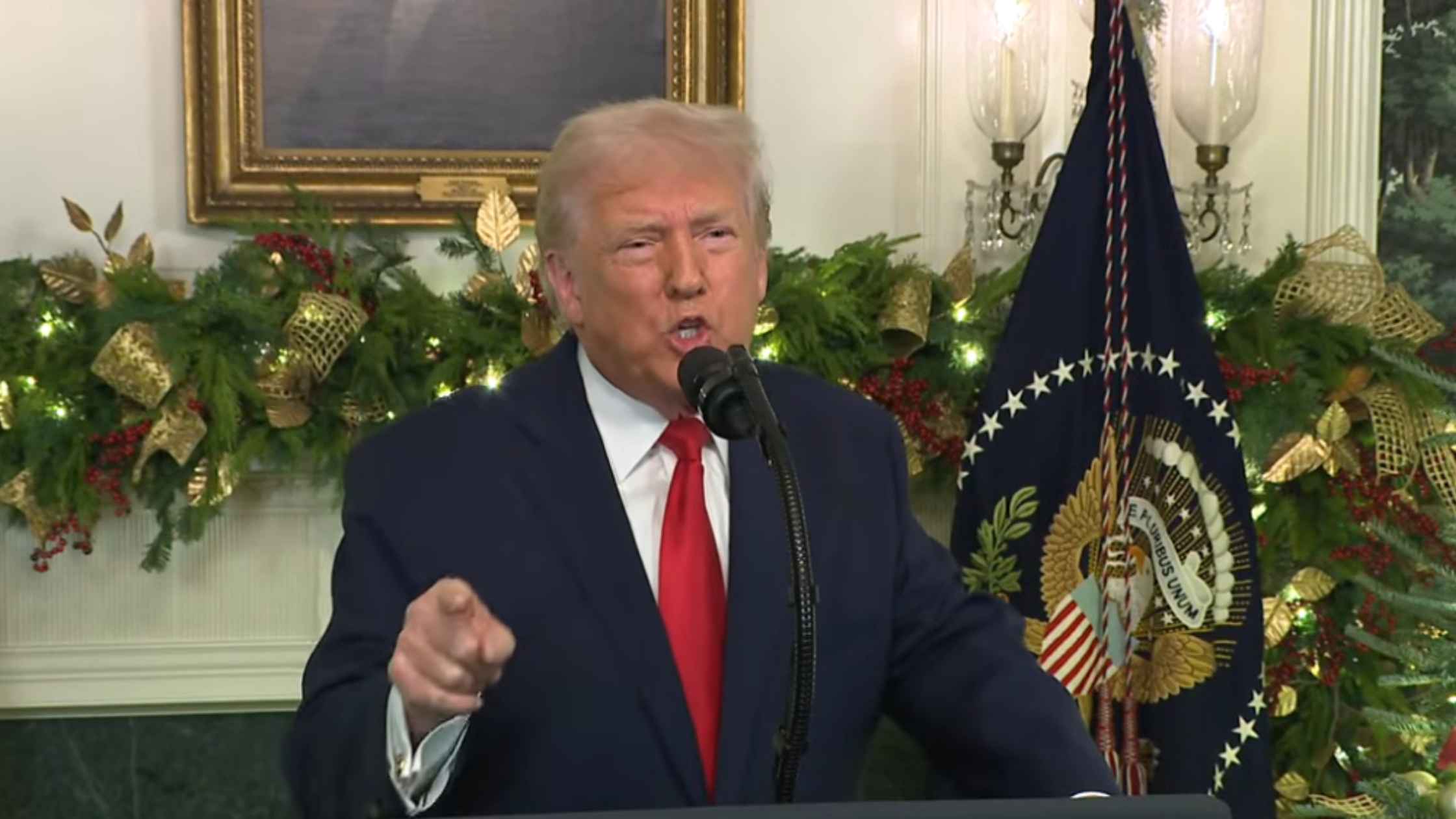

Presidential Address on 12/17/25

Donald Trump gives a Primetime address on 12/17/25. Read the transcript here.

Subscribe to The Rev Blog

Sign up to get Rev content delivered straight to your inbox.