Jerome Powell (00:01):

One, two.

Peter Robinson (00:03):

Those three undergraduates in the front row in the far corner want their picture taken with you.

Jerome Powell (00:08):

I can do that.

Peter Robinson (00:10):

And they've been at me for about a week.

(00:14)

Got it. Okay. Scott, ready to go? Well, we could just enjoy the silence for a moment.

(00:26)

I am Peter Robinson, the Murdoch fellow here at the Hoover Institution. Welcome to the second of three panel discussions in honor of the late Secretary of State and longtime fellow here at the Hoover Institution, George Schultz. The first panel concerned Mr. Schultz as a champion of human rights. The third and final panel will discuss his contributions to foreign policy. This panel is George Schultz as an economist.

(00:57)

With us, Mike Boskin, who has been a Hoover fellow for about a quarter of a century, whose public service includes chairing the President's Council of Economic Advisors, and the administration of President George H.W. Bush. And his private work involves many board memberships, including longtime board membership at Oracle. Condoleezza Rice. I'll go ahead with the introduction just to be… I think everybody knows who Condoleezza Rice is. Public service includes National Security advisor and Secretary of State in the administration of President George W. Bush. Private service includes provost of Stanford University and director of the Hoover Institution, which brings us to the man who wins the award for the most distance traveled to join us here this evening. Jerome Powell earned his undergraduate degree from Princeton and his law degree from Georgetown. I should mention that at Princeton, he was a member of the same eating club as George Schultz, and first became aware of the presence and career of George Schultz by having lunch under George Schultz's picture, correct?

Jerome Powell (02:08):

Something like that.

Peter Robinson (02:08):

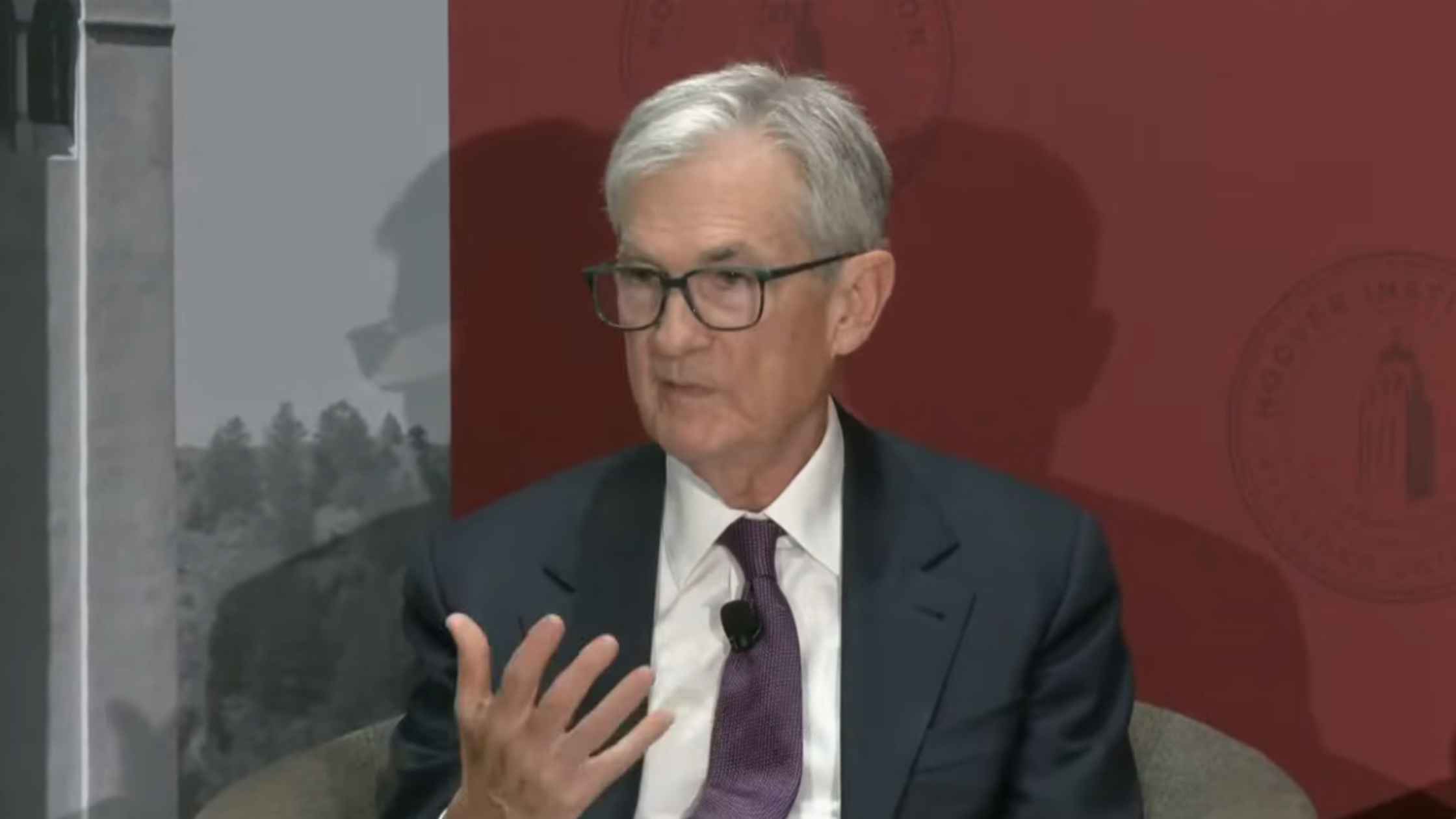

Something like that. All right. Jerome Powell's government service includes service at the Treasury Department during the presidency of George H.W. Bush, his work in the private sector as a partner at the Carlisle Group. Since 2018, Jay Powell has served as chairman of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. Chairman Powell will begin this evening with some brief opening remarks.

(02:34)

Jay?

Jerome Powell (02:35):

Thank you, Peter. Thank you, Condi. Thank you, Michael. And thanks everyone for being here. I'm deeply honored to have been asked to speak here today about the remarkable legacy of George Schultz. And just to be clear right at the start, I will not address current economic conditions or monetary policy.

(02:53)

So I've been an admirer of George Schultz since my college years. I saw him then and now as a great role model as I mentioned just a few months ago when delivering the baccalaureate address to Princeton's class of 2025 50 years after my own graduation. As I told the graduates, when I faced the world after college, I had no real plan, but I knew that I wanted to combine a private sector career with public service. And I had in mind a few well-known public figures of the era, especially George Shultz, who by then had left to go to Bechtel, whose picture, as I recall, was on the wall of the Princeton Eating Club, of which both of us were members of the Quadrangle Club.

(03:35)

George may also have caught my attention because my dad was a labor lawyer who represented one of the major steel companies in collective bargaining. Like George, my father had both a belief in the collective bargaining process and a deep respect for workers.

(03:51)

So I followed George's career with interest through the years. It didn't occur to me that I would ever have the honor of meeting him. But I did meet him after I joined the Fed in 2012 as I visited Stanford from time to time. And I remember energetic economic discussions at group lunches in the conference room at Hoover. George was also kind enough to host John Taylor, Michael, and me for a chilly round of golf on a rainy March day.

(04:17)

So today our focus is on George Shultz's extraordinarily broad economic accomplishments, but I also want to celebrate the remarkable man and policymaker that he was, and several things stand out for me. He was a man who combined strong principles and unshakable integrity with common sense and practical problem-solving approach to policy. He had a deep belief in the wisdom of markets and a desire to let them work whenever possible without government direction. And that theme runs through many of the issues that we'll discuss today, including collective bargaining, wage and price controls, and exchange rates. But he was not an absolutist, and he saw that there are sometimes market failures that do require being addressed by public policy.

(05:04)

As one of the most successful policy makers of his era, George brought the intellectual rigor of an academic to the practical, constrained, messy work of policymaking. Through four cabinet appointments, he dealt with many of the great issues of his day with remarkable success, and he kept at it long after leaving public office, making important contributions here at Hoover on healthcare reform, climate change, nuclear disarmament, and other areas.

(05:32)

He may be less well known for this, but George Shultz was deeply concerned about racial discrimination in the workplace and in our society more broadly. He consistently and effectively used his positions of authority to increase opportunities for minorities, and he later noted that there was both a moral and an economic case for this.

(05:52)

He stuck to his principles while also treating people with honesty and respect, including those with whom he had policy disagreements. Labor leaders welcomed his appointment as Secretary of Labor. And as many of his contemporaries remarked, faced with divergent views and difficult issues, he was extraordinarily good at steering people toward agreement. A key part of that strategy was to let the parties reach the final agreement themselves. That way, they owned the agreement and were more likely to honor it. His friendships and collaborations were beyond number and knew no partisan bounds. He often said that trust is the coin of the realm and that good things were only possible where there was mutual trust. His integrity provided the basis for that trust. All of those who aspire to serve the public can learn from his example.

Peter Robinson (06:42):

Thank you. George Shultz's professional training, labor economics. Mr. Shultz earned his doctorate from MIT in 1949, taught at MIT for nine years, then moved to the University of Chicago where he served for 11 years, six years as Dean of the Business School. Jay, labor economics. The importance of labor in the last century. Help us reconstruct that intellectual world.

Jerome Powell (07:12):

So it was such a different world. Private sector unionization today in the United States is under 6%. In those days it was around 30%. And collective bargaining for the major manufacturing unions in steel and autos and things like that, that was front page news everywhere. The job of the secretary of Labor in any administration was to know the labor movement, know the leaders, and understand what they wanted. It was a very, very different time. And of course, George Shultz had studied collective bargaining. That was one of his main topics in his work as a labor economist. And he was extraordinarily well qualified to face the challenges of a labor secretary and indeed went to Los Angeles to talk to President-elect Nixon just to make sure that President-elect Nixon knew what George's views were on labor economics.

Peter Robinson (08:10):

And he's a labor economist. This is the middle of the last century when there's a great debate about labor taking place in the world. The communists had a certain view about labor. Workers of the world, unite. This is Mr. Shultz. I'm quoting an interview he gave when he was here at Hoover, looking back over his career, "The Chicago School stood for the fundamental value of freedom and free markets."

(08:39)

Mike, Condi, how did he integrate this belief in free markets into labor economics?

Condoleezza Rice (08:47):

Well, let me start by saying that when I was asked to be Secretary of State by President Bush, actually the only person I called to ask about the job was George Schultz. And I said, "So George, what do you think?"

(09:02)

He said, "Well, it's the best job in government."

(09:05)

And I said, "Well, George, you should know because you've held almost every other job in government." But the reason that he said that is perhaps part of the answer to your question, Peter. He said that he always fundamentally believed that the United States had the right foundational principles and that that was much of the reason for our success. One of those foundational principles was of course the free market. And of course, the Chicago school spread, particularly in Latin America and other places, had he thought the chance to bring other countries out of poverty to use their resources best and to gain prosperity.

(09:44)

But he also believed in the inextricable link between free markets and individual liberty. And that reflected in the way that he took on the challenge, of course, being the Secretary of State as the Soviet Union was beginning to go into its twilight. We forget that George's first year as secretary, the Soviet Union was a bit on the march. It was 1982, '83, '84, the sense that the Soviet Union was really the future. And from George's point of view, this was nonsense. And this is something that he shared of course with Ronald Reagan, that this experiment, as Reagan had called it, this experiment that was practiced on a hapless people would end up on the ash-heap of history.

(10:35)

Now, George, who was a great diplomat, would never have said it so boldly as Reagan did. But because they believed in the fundamental principles of the free market and individual liberty, the Soviet Union was on the wrong side of history. And they were together, perfectly willing to say that, perfectly willing to challenge the system. There's a story that Mike likes to tell of George meeting with Gorbachev and saying to Gorbachev, "You know that central planning thing that you've got going, maybe you'd better take off with planning because you all aren't doing it very well." And can you imagine Gorbachev at that point thinking, "Who is this guy and why is he telling me about my own economy?" But because he had been a great economist, because he'd been Secretary of the Treasury, I think George was able to bring this knowledge of how the free market worked, along with his belief in the free market and his belief in individual liberty to really challenge many of the assumptions about the strength of the Soviet Union at that particular point in time. And then to be there, of course, for the beginning of the end.

Peter Robinson (11:47):

Mike, a question for you on the longshoreman strike. Let me set it up. The Nixon years, just after George becomes Secretary of Labor under President Nixon in January '69, he finds himself confronted with the longshoreman strike. He's under intense pressure for the government to intervene, but he insists on keeping the federal government out of it, forcing the longshoreman and management to the bargaining table on their own. Instead of damaging the entire economy, the strike settles just a month after George Schultz takes office. Why was that such an important episode?

Mike Boskin (12:23):

Well, first of all, it set a really important example, number one, that government intervention sometimes can be an obstacle rather than a provider of successful outcomes. Number two, it's really important because it signaled that people could make their own decisions and would be forced to if they were confronting each other, rather than wait around for the government to come in. They wouldn't make their best offers, they wouldn't get serious.

(12:51)

This became very clear to me. I was a beneficiary of George's advice and friendship, and we did a lot of things together over the years. Maybe talk about that a bit later. But it becomes really apparent when you're dealing with a whole different context than people that aren't used to thinking about markets, people that aren't used to thinking about individual incentives, people being able to think that way. And that goes back to your and Jay's comments and Condi's about as being an economist.

(13:20)

He was used to this idea that people were trying to do the best they can themselves given their environment. And that if you let them do that, that would collectively lead to the best possible outcome. Kind of a basic theorem of basic economics, which some people forget. And there's always a pressure for the government to do something if all of us have been in [inaudible 00:13:42] still is, but in public office, and the first thing every morning in the briefing room is, what's the president going to do about X? And it could be anything. It could be anything the president shouldn't have any worry about, shouldn't even know about. So it's important to set that example and to let things play out until there really is something that you desperately need the government to intervene for, if that happens.

Peter Robinson (14:05):

Two incidents in the Nixon years that are less, strictly speaking, economic than social. The Philadelphia Plan. In the spring of 1969, George Schultz issues the Philadelphia Plan, which requires federal contractors to hire minority workers. And he famously makes the remark that he's not imposing quotas. He's ending a quota. And the quota that he was ending was on Black workers and it was zero.

(14:34)

As Secretary of Labor, he also ran the White House Cabinet Committee on Education, which was charged with developing a strategy for the peaceful integration of schools in the seven states of the deep South. He ended up running it because Vice President Spiro Agnew wanted nothing do with it. He was given the chairmanship and never turned up for any meetings.

(14:56)

There's a famous moment, I've heard Mr. Schultz himself tell this story, George Schultz has the chairs of the Mississippi Committee come in. It's a white man and a Black man, and he has them sit down together in the White House. And as they get close to an agreement, Secretary of State leaves the room. And I'm quoting George Schultz here, "I learned long ago…" You mentioned this in your remarks, Jay. "I learned long ago that when parties get this close to an agreement, it's best to let them complete their deal on their own. That way the agreement belongs to them."

(15:28)

By the end of the Nixon administration, this is a statistic I found staggering, I wasn't aware of it, more than 90% of Black children in the South were attending integrated schools.

(15:39)

All right. He's a labor economist, but in the Philadelphia Plan and the in integration of schools in the South, he's solving social problems. What's going on here? This has something to do with his own principles, with the respect in which everyone holds him.

(15:57)

Jay, would you like to address these episodes?

Jerome Powell (00:00):

Jerome Powell (16:00):

… I would. So this is something that people need to know more about George Schultz. This is an extraordinary accomplishment and it is consistent through his career. He started the first minority program to bring kids into the University of Chicago Business School and many other things along the way. But in this case, Brown v. Board is decided in 1954, this is 15 years later and there's seven Southern states that have just not desegregated their schools. Supreme Court makes it clear that the argument is over and we're going to do this. George Schultz, he takes over this commission and he picks a Black person and a white person from each of the seven states.

(16:40)

He gets them together and they figure out how to do this because they now know this is going to happen and he gets them to realize that. And the whole idea is this got to be done without violence. And he manages to get that done. It's an extraordinary accomplishment. How did he do it? This is sort of the full Schultz playbook of bringing people together, treating them with respect, empowering them, enabling them to take on this thing, this terrible, difficult issue. And it really worked. I mean, the schools did open without violence in these seven Southern states and it's quite a remarkable story and he really made it happen. So quite extraordinary.

Condoleezza Rice (17:17):

Well, actually I lived it because I was a kid in elementary school in Birmingham, Alabama in the early 1960s. And Brown versus Board of Education 54, essentially nothing happens in integration of the schools despite the striking down of separate but equal.

Peter Robinson (17:39):

They just ignored it.

Condoleezza Rice (17:40):

They just ignored it. Just ignored it. And then finally after the Supreme Court, so they came up with this plan just before Georgia's intervention called Choice. Now Choice is a good thing these days. In those days it wasn't particularly a good idea, because the idea was probably white parents would choose to keep their kids in white schools and Black parents would choose to send their kids to white schools. As it turns out, nobody chose to do anything. And this is actually kind of a funny story. A few poor teachers were sent to integrate the faculties of these schools. And my mother was one who was going to be sent to a white school.

Peter Robinson (18:27):

Really?

Condoleezza Rice (18:27):

Yes. My father was terrified because he was worried about the potential violence. As it turns out, my mother didn't go, but they sent this poor white woman to our school at Druid High School. And I felt so bad for her because everybody just treated her really, really badly. She was the only one. So this was going pretty imperfectly. I told this story to George, and I think one reason it was important to get people together and then get a plan for how to do this, which is what the Philadelphia plan really was, was because it was going nowhere and to the degree that it was going anywhere, it wasn't going in a very good direction. And so George and I would kind of laugh about my own personal experience in what was going on in the South before the Philadelphia plan.

Mike Boskin (19:15):

It's worth mentioning that affirmative action has gotten a bad name of late and California voters have rejected it twice and perhaps it went overboard a bit. But back then in the Philadelphia building trades, there was a quota of zero African Americans. And so economists hate quotas and a quota of zero is a bad quota, just like a quote of a large amount. So I think it reflects back on his thinking as an economist. And as Jay said, there was obviously a moral as well as a economic justification.

Condoleezza Rice (19:47):

Well, I think he felt the moral side very strongly because both in the Philadelphia plan and in the work with the school system, because again, it went back to Georgia's view that America was the hope of the world. America was the place that had gotten it mostly right, but there were times when America had not gotten it right. And on this, we had not.

Peter Robinson (20:09):

Back to economics and mixed administration. And here I'm going to ask the three of you just to give me a seminar. We've got the closing of the gold window and we've got wage and price controls. So I'll set up with what I know, which is very little. In 1970, Mr. Schultz becomes director of OMB. He's one of a circle of advisors, including Secretary of Treasury, John Connolly and under Secretary of the Treasury, Paul Volcker, who advised President Nixon to end the convertibility of the dollar into gold. President Nixon closes the gold window on August 15th, 1971. I'm going to quote Milton Friedman, his observation on this, quote, "The closing of the gold window opened the way to a free market for the dollar where there was none before," close quote. Again, we're dealing with something here so foreign to the way we do business and think about the currencies today that requires a little bit of effort simply to take us back to the moment when the dollar was pegged to gold and what the debate concerned, why it was important. Who would like to take on? Mike, start us.

Mike Boskin (21:25):

I'll start. So if we go back to the end of World War II and what George and Condi like to call the global economic and security commons was established, the International Monetary Fund, the general agreement on tariffs and trade and the World Bank were established. And we established that the dollar as the centerpiece of the exchange rate system. Most countries would have fixed exchange rates and the US would peg the exchange dollars for $35 per ounce of gold and a pledged to do that for the foreign reserves, dollar reserves of foreign countries. So this again was George in the international arena as well because it affected other countries.

Peter Robinson (22:08):

That enabled us to backstop economic growth across much of the world. Is that the idea?

Mike Boskin (22:13):

It's a little more complicated than that. And I don't want to bore people in the audience with this, but what it meant was you could not have other countries and could not have an independent monetary policy along with the fixed exchange rates and free capital flows. Because if their interest rates were lower than ours, capital would flow out, they'd be pressured to devalue their currencies and the opposite if their interest rates were higher than ours. So it created quite a conundrum and we've seen that in more recent years when countries have pegged their currency to the dollar ended that and we've seen what happens. It was a little chaotic. So this I think was a major move.

(22:53)

There had been a big intellectual debate for decades in economics about whether fixed or flexible exchange rates were better. And I think the flexible market oriented approach wound up winning, I think, to the world's advantage. So that was part one. Part two was because of this sudden change and we weren't going to exchange $35 for an ounce of gold anymore, foreigners were foreign holders of US dollar reserves were going to be in a pickle. And so we couldn't revalue the dollar. They had to revalue against us. And so what happened was President Nixon imposed a 10% import charge that was going to be removed if and when they revalued their currencies appropriately, which is what happened. And within 18 months, the world kind of came to a bit of a equilibrium and things were going okay. And then a year later we had the oil shock Jay referred to earlier.

Peter Robinson (23:56):

And so I can't resist asking the chairman of the Fed if it worked. If we hadn't had the oil shock, it was a good idea.

Jerome Powell (24:07):

We were going to switch to a floating rate system eventually. Milton Friedman was right about this and it was a good thing that we did.

Peter Robinson (24:13):

Okay. So this brings us, Condi, would you hop in on the gold window?

Condoleezza Rice (24:18):

Which person here is not like the others? I'll leave that to the economist.

Peter Robinson (24:24):

All right. Then the wage and price controls, again, I'll set it up. President Nixon imposes wage and price controls. Director, as he was then, director of the Office of Management and Budget, George Schultz opposes the measure, but finds himself overruled by John Connolly, a secretary of the Treasury and Richard Nixon. In 1972, George Schultz himself become Secretary of the Treasury and by January 1973, he had abolished most of the mandatory controls. He abolished the controls entirely in April 1974, just before stepping down as Secretary of the Treasury in May. So again, it is inconceivable. The notion that a President of the United States would impose wage and price control strikes me as inconceivable now. So we need this sort of reconstruction of what were they thinking. And then also, is it fair to see this as this episode is a kind of the old statist view represented by John Connelly versus the new Chicago school thinking in terms of free markets represented by George Schultz? Is it as simple and straightforward as that? Mike, do you want to take a shot at this?

Mike Boskin (25:35):

Yeah. For many, many decades, economists have debated and we thought we had won this battle, but it's come back several times since. The propriety of using what's called incomes policies, which were basically the government jaw-boning business and labor, which may have made sense in the economy where a large fraction of the labor force was unionized, unions were very powerful. If it made sense at all, that's when it made sense. But any event, we wound up in this situation where we had just a remarkable series of key intellectuals coming to the conclusion that we weren't really sure what we could do about inflation and unemployment occurring at the same time. We had to do something. We didn't want to inflict any pain about disinflating the economy and causing a recession. We couldn't use monetary and fiscal policy very well.

(26:29)

And this became a big debate and we thought it had ended successfully with the end of wage and price controls, but it came back. In fact, when I was advising candidate Reagan in 1980, the campaign asked me to debate Walter Heller, who'd been President Kennedy's chair of the Council of Economic Advisor and a key architect of the Kennedy tax cuts on this precise point. And you had like the head of the AFL CIO, key industrial business leaders, like the heads of DuPont, Lane Kirkland and Shapiro, they would decide what to do with the government in the room, kind of getting back to the point Jay made earlier. And fortunately that didn't happen. We had a successful, if painful disinflation, but I'll turn it back to Jay because I know he has some views on this as well.

Peter Robinson (27:18):

Yes, Jay.

Jerome Powell (27:19):

So, I mean, the interesting thing to me is that as Michael pointed out, there was almost a consensus that we needed income policy. And in other words, that the government needed to jawbone companies informally at least, let alone, and then maybe would eventually need to do wage and price control. So if you go back to 1966, George Schultz had held a famous conference with another University of Chicago person and it was on guidelines and the big names of the heir debated. Milton Freeman famously debated Bob Solo over this, but people really thought that there was a problem to solve. There was a general agreement that the problem of high inflation and high unemployment, that fiscal policy wasn't going to be able to handle that. Monetary policy wasn't. So you needed the government to somehow do this. This was a bad idea. It was a really bad idea and somehow it had become approximately conventional wisdom in these days. Milton Friedman, of course, was a big exception. George Schultz was on the right side of that.

(28:20)

Paul Volcker was on the right side of that. But to me, there's a takeaway there, which is that our understanding of the economy is ever evolving. The economy itself is ever evolving. So I think we always, those of us who are doing economic policy have always got to remember that the structure of the economy is always changing and that our understanding of it is always highly uncertain. So certain things that are sometimes accepted as conventional wisdom, people will look back in 50 years and think like we're doing with wage price controls, they're going to say, "What were they thinking at the time?" Well, that's what they were thinking. They were thinking it was really the beginnings of stagflation, high unemployment and high inflation. What do we do? Very difficult problem. And Paul Volcker kind of had the answer and eventually did it. George Schultz deserves credit for supporting him and Reagan deserves credit for supporting him as well.

Peter Robinson (29:14):

Condi first.

Condoleezza Rice (29:16):

Yeah. I was just going to say that this is also quintessentially George Schultz. So he lost the argument, but he understood who was elected and he was able to bide his time and then we had the opportunity. He worked to move things in the other direction. But George was, in that way, quintessentially a pragmatist always also.

Peter Robinson (29:41):

He played a long game.

Condoleezza Rice (29:42):

He played a long game. And I think it isn't as well understood that when you're in government sometimes, you're going to win some and you're going to lose some, but if you never lose sight of what you think is right, you might have a chance to correct it. And I know that the wage and price controls for George, this was really an anathema. And he thought one of the arguments that he was most unhappy that he lost because he thought it did great damage, but when he had the opportunity, he reversed it.

Mike Boskin (30:10):

Just my quick comment with respect to Condi's comment about winning some losing, we always thought we were doing well if we were above Shaq's free throw percentage, but it's important to remember what was going on in the economy, as Jay has mentioned. Nixon imposed wage and price controls when inflation got up to 4%. It's important to have that historical reference in the back of your mind.

Peter Robinson (30:34):

So thank you for the seminar. What I hadn't realized is the extent to which there was a debate going on within the discipline of economics when the shock hits, which means you don't have… I don't know how to put it… I don't want to use the word establishment, but you don't have consensus on how to respond when the oil shock hits. In the '70s, the economy is taking one blow after another and the economists, there's a debate about what should be done. There's a kind of uncertainty. Is that fair? A fair description?

Mike Boskin (31:09):

Absolutely. Absolutely

Peter Robinson (31:09):

All right. So then we get to Ronald Reagan and I hadn't thought of it this way before, but this is a moment when one side wins the debate is one way of thinking about it. George Schultz, before becoming Secretary of State, which he did about a year into the administration, he chaired President Reagan's economic policy advisory group, a group that included figures such as Milton Friedman. This is Mr. Schultz in a 2000 interview talking about those times. The advisory group said the essence of the inflation problem is monetary policy and to deal with it effectively, you've got to discipline the money supply. People warn President Reagan that if he did this, there's likely to be a recession. By the way, I was there for that bit and people did warn him of just that. Back to George Schultz, but he did the right thing

Peter Robinson (32:00):

"And we did have a recession, but inflation dropped like a stone, and that has been one of the primary reasons why our economy has been as strong as it has been." So from Richard Nixon's wage on price controls to the moment when Ronald Reagan backs Paul Volcker in disciplining the dollar represents an intellectual, it's not just a pol…, it's an intellectual victory. Is that right? Am I understanding that correctly?

Mike Boskin (32:29):

In that ten-year period, we also had President Carter in 1979, go on national television, complain about high inflation and malaise said the Fed should lower interest rates to reduce inflation. So there's a lot of misunderstanding in the polity as well. But it's a remarkable transformation, in 1979, this goes back to Condi's discussion of George liked to garden, but he also did that in economic policy, not only bided his time and changed things when he had the opportunity, but he prepared.

(33:02)

And so in 1979, he had a dinner with candidate Reagan, and he invited myself and Milton Friedman and a couple of other economists to kick the tires about supply side economics and about inflation. And I was very, very much impressed because Reagan's knowledge and subtlety of understanding these things, the depth of understanding, was quite a bit different from the caricature of his portrayal at the time. And so I think that George was preparing for this moment and letting Reagan talk to some people that he came to respect that worked with him and for him, and developed an understanding. And Reagan also had very strong principles, and he understood how serious high inflation was.

(33:48)

Keynes in a remarkable book, in 1919, saying, what will happen from the Treaty of Versailles, hyperinflation, et cetera, in Germany that'll destroy the society quoted Lenin's injunction that "Debauching the currency is the surest way to destroy capitalism." And so it's a very, very strong sense in Reagan that we have at the time, inflation is double digits and had been rising at the same point of every business cycle since the 1960s. You measure the trough, the midpoint or the peak, it's going up and up and up, and it peaked at around 13%. And so there was a desperate need to disinflate the economy. It was painful, but it was the right thing to do.

Peter Robinson (34:33):

Condi, you remember those, well, you were still at Denver, weren't you?

Condoleezza Rice (34:38):

No, I just become a faculty member at Stanford and was trying to buy a house. And I do remember [inaudible 00:34:45].

Peter Robinson (34:43):

So you do remember inflation?

Condoleezza Rice (34:44):

I remember it very, very well.

Peter Robinson (34:45):

You remember interest rates.

Condoleezza Rice (34:46):

But I was going to make a point about George in this regard because we all know that George Schultz was a very fine public servant and it was mentioned he was also an academic and he cared about these intellectual debates. He cared about winning the debate with ideas. It wasn't name-calling, it wasn't, you're just evil. He actually liked to get ideas on the table and debate them, and he liked to debate them with people who disagreed.

(35:16)

And when he had an opportunity with Reagan, he brought people together for Reagan to listen and to hear the ideas. Mike mentioned this because you were there, I would see it later with George W. Bush in that George would bring together these groups of people for these politicians and he would count on the ability to convince and persuade through good ideas, to really challenge people who wanted to be the elected officials who were going to carry out policy to really understand what they were listening to.

(35:50)

I have to say, the Hoover Institution played quite an important role in this. People like Milton Friedman and others, Mike Boskin, but it was George who would convene these people with people who were going to actually be in government, who were actually going to run for office. We sometimes, as people in the academy or people who, like Mike and I or Jay, have served in government, people say, well, I like policy but not politics. Well, unfortunately, policy has to go through politics to actually become policy. And George understood that. And so he often spent a lot of time with the people who were actually making decisions, trying to convince them. And with Ronald Reagan, he found somebody who had everything that needed to change many of our assumptions about the way the world worked.

Mike Boskin (36:43):

It wasn't just in Washington, the second time, George dragooned me into doing so, and the first time when his Treasury secretary, he called me, I'd never met him, and he got me involved, Marty Feldstein, as the advisor to a commission to talk about the benefits of philanthropy and the benefits of the tax deduction for raising lots of money for charities, probably more than the government was losing in revenue by allowing the deduction.

(37:04)

Then a few years later, it was to go up to Sacramento, talk to then Governor Brown in his first of his two, two-term stints as governor, and the Californians were running a large surplus. We had a very high inflation. The tax brackets weren't indexed, so revenue was rolling into the state and property taxes were going up because they were being revalued. And the governor wanted to convince us to back him running a bigger and bigger surplus, which I think he wanted to do to later on have an even larger tax cut and run for president. But in any event, so we went up there. An acute anecdotist, at the time he was dating Linda Ronstadt, and so…

Condoleezza Rice (37:44):

He? Governor Brown?

Mike Boskin (37:47):

Governor Brown, not George.

Condoleezza Rice (37:48):

Not George.

Mike Boskin (37:50):

Absolutely, Obie wouldn't have gone for that. And lunch was kind of dietetic, he was in training. In any event, we thought this was a bad idea, and that's one of the untold stories of how Prop 13, California's property tax revolt and initiative that limited property tax increases, happened because this was going on while the state had a gigantic surplus.

Peter Robinson (38:16):

Jay, can you work Linda Ronstadt into…?

Jerome Powell (38:19):

I don't think I can.

Peter Robinson (38:20):

All right, then. So when you look back on this episode with Nixon, which I now see actually it's important to understand it as part of a continuum from Nixon wage and price controls to what takes place in '81 backing Volcker to shrink the money supply. I'm struck that again and again, George Shultz is there. Furthermore that he would think of him, so often people emphasize character, which is totally fair and true, of course, but he took the life of the mind, this is the point Condi made, he took his intellectual life extremely seriously.

(39:07)

And we've got this intellectual project taking place at the University of Chicago. They believe they reach conclusions, Milton Friedman and George Stigler and George Shultz, and then it's George Shultz who has this kind of genius to take the intellectual findings and work this strange territory between intellectuals and office holders to get the right thing done. So what does that…? Now, I know you knew George Shultz the least, but I actually find that a striking datum that you took the time to fly out here because he means so much to you as an example. So what does that tell us about the way an intellectual, an academic, goes about public service at its best?

Jerome Powell (39:59):

So, obviously, the big things he got right. So collective bargaining he got right, exchange rates he got right, wage and price controls, he was right on those issues, and history has very much vindicated that. And of course, he was a great Secretary of State and helped end the Cold War. Maybe we could be here just listing his, let alone discussing his many accomplishments.

(40:23)

But I would say as important as his extraordinary achievements is the way he approached public policy. It resonates very much with me the way he brought people together with respect and integrity and wound up being able to foster agreements on super difficult issues like this desegregation of schools in the deep South and many other areas. He was an extraordinary public servant, even if you didn't agree with those policy conclusions, which I did. So that's another aspect.

Mike Boskin (41:00):

He continued to do that until very late in life. He was convening things at [inaudible 00:41:04] Hoover. He was a huge presence here. He often convened groups on various issues. I was privileged to do many, sometimes with colleagues here, especially John Cogan and John Taylor on economic stuff. But he always tried to get alternative points of view.

(41:21)

He tried to get people debating and discussing, and he tried to get people in a conference room in, we called the Annenberg here, and we would sit there and we'd understand facts and theories and data and history and debate about what the best path forward was on a variety of pretty complicated issues that often don't have just singularly clear conclusions, but have trade-offs involve something else, that being an economist teaches you to pay a lot of attention to.

Peter Robinson (41:50):

George Shultz as teacher. George Shultz becomes Secretary of State in 1982, and he serves until the end of the Reagan administration. Most of his work as Secretary of State will belong to the third of these conversations about him. But there's an episode or an aspect of his time as Secretary of State that shows George Shultz right back where he started, teaching economics. I'm quoting now from The Cold War by John Lewis Gaddis.

(42:19)

Gaddis notes that "As early as 1985, Secretary of State, George Shultz began telling General Secretary Gorbachev that the Soviet Union would continue falling behind as long as it had a command economy." Now, I'm quoting Gaddis, "You should take over the planning office here in Moscow, Gorbachev joked, because you have more ideas than they have. In a way, that is what Shultz did. Over the next several years, he used his trips to Moscow to run tutorials for Gorbachev and his advisors, even bringing pie charts to the Kremlin. Gorbachev proved surprisingly receptive." Condi, what this is, I mean, it sounds almost like a Monty Python sketch, but it happened.

Condoleezza Rice (43:11):

Right. And look, I think this is one where George had mixed results, and I would say they were mixed results because it was very hard to penetrate the Gorbachev, or any of them, the idea that this thing called capitalism and markets could actually make everybody richer. And I remember Gorbachev saying at one point, actually, George H.W. Bush, he was trying to explain how in capitalism somebody will found a company, and yes, they'll get rich from that, but there'll be all these jobs and the economy will grow and so forth and so on. And at one point, George H.W. Bush turned to me and said, "Are they translating this?" And I said, "Mr. president, I'm afraid this just doesn't translate."

(43:59)

But George was indefatigable. He would go and he would take his pie charts and he would explain why central planning didn't work. And maybe underneath it eventually had an effect, because one of the things that Gorbachev tried to do, and George was very proud of this, was he actually tried to have these little private enterprise shoots. They wouldn't privatize the economy as a whole, but they had little entrepreneurial businesses that they started to build called collectives so that somebody would be able to have a restaurant that was private.

(44:34)

And this is sort of 1987, 1988, and George actually would go once in a while to these little collectives where a man and his wife, you could only have eight tables, by the way, you couldn't have more than eight tables, and so he would go because, and by the way, much to the chagrin of the diplomatic security and the like, he would go down into some town and go to one of these collectives because he actually did believe that that could be the beginning of capitalism. So he understood that it was too much to try to explain to them that you could have this thing called the market and it would all work out. But these little experiments, he was always very proud of and thought maybe you'd had a part in getting them to do it.

Mike Boskin (45:20):

I can pick up on that, because I got to deal with it subsequently when the Berlin Wall fell, et cetera. And so first of all, Gorbachev may have been receptive, but he didn't understand it. He had grown up in the agriculture, he was Secretary of Agriculture, and they were making sure he knew exactly where everything was all the time. So when Senior Bush sent me to help them with economic reform, because they announced they were going to become a capitalist economy in 500 days, not the five centuries it took to develop capitalism, but that's a whole other story. So I met with Gorbachev and Shevardnadze, and it's pretty clear I'm Bush's chief economic advisor, so I actually know how all this works. So he sends me to see the head of Gosplan, the state planning agency. Through his interpreter, he asked me, "Who sets the prices in your economy?" And I tried to explain, we have a few regulated industries and there's… Et cetera. And I've won teaching awards in my day, but he wasn't having it. He just didn't understand that lots of consumers, lots of producers can interact and that would determine prices, et cetera. And so he finally gets very frustrated, motions me to wait. He goes back into his office, we're in an ante room, comes back with one of these 1970s we would think of here, but then it's 1990 flip charts, and it's these Fortran flip charts, it's the price list for the Soviet Union.

(46:40)

He hands me a pen, he wants me to cross out the old prices and write the new ones. He can't believe… Since Gorbachev has told him, I'm Bush's chief economic advisor, I know what the price should be. So he's convinced that I should just write in new prices and that would solve his problem because he's been told he has to get to a price system in 500 days and he hasn't the slightest idea what he's doing. Both in China and in Russia I've had the experience of people who were more reformers, who spoke some English, but also generally relied on translation to be precise, tell me that you can't get this across because all these people have been trained as Marxists.

(47:19)

When we ask them, how do you know what's actually going on in the economy? They've never thought about how to measure something like GDP because the outputs are weighted by market prices. They don't have market prices. They're just used to everything being quantities. These many shoes of this size for this style of lady's shoe will get shipped to Leningrad or to Vostok, et cetera. That's all they knew. So in any event, it became interesting. And later on, George was a big help to me and Condi, who was a rising superstar on the NSC staff at the time, when I was asked to negotiate a potential bailout with Gorbachev. And he told me, "Push them hard. They have to threaten to walk out twice so they don't get serious.

Mike Boskin (48:00):

… and then be careful because you can do more harm than good. That's why we decided to do… Even though Bush was being pressured by John Major and François Mitterrand on Helmut Kohl to bail out Gorbachev, we decided to do very little.

Peter Robinson (48:14):

Jay, I'm wondering if you'll buy this idea that this represents another aspect of the way George Shultz did public service. He was always teaching. Gorbachev in this case, but I think… Condi, I think back to his, there would be some big meeting, some big summit, and he would go to the press.

Condoleezza Rice (48:36):

Yeah.

Peter Robinson (48:37):

It would be very methodical.

Condoleezza Rice (48:39):

Yes.

Peter Robinson (48:39):

He would want everyone to understand what had happened, what were the central issues, who took what position, and where matters stood now.

Condoleezza Rice (48:48):

George never talked in sound bites.

Peter Robinson (48:51):

No.

Condoleezza Rice (48:51):

He simply didn't. There was always depth to it. I think sometimes it was a little frustrating for the press because they wanted him to talk in sound bites. Having been in that job, I know they'd like you to talk in sound bites, but he was determined that people were going to have a real understanding of it.

Peter Robinson (49:08):

Jay is not known for soundbites either [inaudible 00:49:10]-

Condoleezza Rice (49:09):

No. No.

Mike Boskin (49:11):

Yeah. No. I would say also George in a sense was AI before AI because having been in boardrooms and academic seminars, he always would listen carefully and he would summarize things in a way that really got to the essence of the issue and what the issues were and what the path forward or the potential paths forward were. It was quite an amazing thing. It's in the boardroom and people would be arguing about this, that and the other thing. He'd just sit there quietly, and at the end he'd give a succinct, maybe not always a succinct summary, and wrap things up.

Peter Robinson (49:44):

Jay?

Jerome Powell (49:46):

I think I didn't know him anything like both of these folks knew him, but it seems to me people who met him and worked with him trusted him. It was based on his integrity and his knowledge and his work product and just the way he dealt with people. He holds three cabinet… In ascending importance, labor, OMB, and then treasury in three years really.

Peter Robinson (50:09):

That's right.

Jerome Powell (50:09):

He's getting promoted really quickly and being given the job of desegregating the schools, which wasn't obviously connected to any of those jobs. Then as Secretary of State, Gorbachev and Shevardnadze just take tremendous liking to him and they want to work with him. Some of the people who study this stuff give him a lot of credit for… He didn't compromise on his principles, but they trusted him and they felt that this was someone they could work with and that President Reagan was really aligned with, critically Reagan was aligned with these goals. He was just very effective in that way. Again, I think it was liking him, trusting him, having strong principles that he didn't compromise, just made him very effective, remarkably effective across so many issues.

Peter Robinson (50:56):

Back at Stanford, after the Reagan administration, Mr. Shultz returns to Stanford, he composes his memoirs, Triumph and Turmoil, he convenes study groups, he continues coming into his Hoover office well into his… I think he was still showing up in his-

Condoleezza Rice (51:11):

[inaudible 00:51:12] late-

Peter Robinson (51:12):

… 99th year as I recall.

Condoleezza Rice (51:13):

… very late 90s. Yes.

Peter Robinson (51:14):

Two or three days a week in his…

Condoleezza Rice (51:15):

Yes.

Peter Robinson (51:16):

Which is by the way, is about as often as kids show up for in the office these days, two or three days a week. I am just struck that the same things he was doing at the University of Chicago in all of these… Secretary of Labor, director of OMB, Secretary of the Treasury, Secretary of State, he continues to do here at the Hoover Institution, convene, talk. That says something about him, of course. Let me know what you think it says about him that he keeps at it so long, but it also says something about the Hoover Institution, that this remarkable man thought that it was worth making this institution the central activity of his life for the final decades of his time on this planet. Condi?

Condoleezza Rice (52:08):

Well, we called him the great convener because George would… Really, he would decide that there was a subject that was of importance and we ought to get the smartest people in the room to talk about it. It was that simple. Then he would call them up and of course they would all show up. Everything from… It was not just economics. Mike mentioned he had a very deep interest in California and in trying to make this state better. You might know that Charlotte, the great Charlotte, was chief of protocol to several mayors and governors of the state. He was very involved in California and in California policy. Not so much politics, but policy. George took a tremendous interest in energy policy, and together with Tom Stevenson, convened a task force on energy in which they were concerned, not just about energy, but about the issues that related to a clean environment, the climate change, and so worked very hard on those issues.

(53:14)

Obviously, anything to do with national security. Another area that people perhaps don't realize how important he thought it was, North America. He cared about North America because he believed it could be an economic engine. If you thought about the assets of Canada, the United States and Mexico together, that this could be a tremendous economic engine. I always thought of Georgia's life as an economist, his understanding of the economy, and the way that he engaged these incredibly important public policy issues as being inherently linked. It goes back to that belief in markets, to that belief in free enterprise, to that belief in individual liberty. It would all show up in these convenings that George would do, but his reach across so many public policy issues, very often starting from the economic side and branching out is really quite extraordinary. I think it made him a far better Secretary of State because he really understood what a lot of these countries were trying to do in providing for their people.

Mike Boskin (54:23):

Yeah. It made Hoover and George a perfect compliment to each other because of the wide breadth of interests of the Hoover Scholars. We have experts in economics and national security and foreign affairs and education and political science. You go on and on energy, et cetera. We have area studies of particular interest, and George was really, in a sense, interested in everything or as much as he could with his immense capacity [inaudible 00:54:53].

Peter Robinson (54:53):

Couple last questions for all three of you. If possible, we'll go right down. I'm struck by this notion that he participates, he's right in the middle of a great debate that takes place for a couple of decades in this country. By the 1980s, when we get economic revival and a victory in the Cold War, it feels as though we've gotten someplace. It feels as though one side of the debate has won, which brings us to today. The former Soviet Union, now Russia, still has not embraced free markets. China has embraced markets, but has not embraced democracy.

(55:37)

The economy that we inhabit, which AI, every person I know who… Even people who are making money on AI already are nervous about what it's going to do to the labor force, restructuring jobs. We've got new forms of currency. This is always a question that you really can't get… It's not a rigorous question, but at the same time it gets at something. What would George Shultz tell us today? What are the permanent lessons that we should grasp as we face this changed world in which we live? Mike, would you like to go [inaudible 00:56:15]-

Mike Boskin (56:15):

Yeah. I would say that at the core of the way George thought about things was combining facts, ideas, and experience. He firmly believed you didn't really understand something deeply unless you understood it intellectually and had experienced it in your gut. I've come to that point of view over a long time, partly under George's influence, but just my own experiences. I think he would try to make sure that you merge those things in your thinking about issues. Number two, he would say, stay engaged. Stay engaged. Try to be constructive in any way you can. To me, that's a great lesson from his life. Stay engaged whether that's in the cabinet at the federal government level, whether it's your local school board or whatever you happen to do. Stay engaged and try to make things better. He loved the phrase, "Democracy's not a spectator sport," and so Stay engaged.

Peter Robinson (57:10):

Jay, what are the permanent lessons?

Jerome Powell (57:13):

I agree with all of that. History doesn't end, so now we're into a whole different set of challenges looking forward. We need to remain engaged, to Michael's point, with our main allies and rivals. We just need to keep working on all the things that we confront now, which to some extent some of the issues are settled, like the issue of price controls is no longer… We understand now that the central bank is responsible for price stability. That issue is settled. It doesn't mean it's easy to do, but the issue is settled. It's just new issues.

Peter Robinson (57:53):

You make so easy. You make it look so easy, Jay.

Jerome Powell (57:54):

Yeah. That's the trick.

Condoleezza Rice (57:56):

Yeah.

Jerome Powell (57:58):

No, but so things like nuclear disarmament, we were talking more… We were probably closer to that 20 years ago than we are now. These issues don't go away and new issues arise. I call for very much, I think that the way George Shultz approached public policy and engagement are exactly what we need now.

Condoleezza Rice (58:16):

Yeah.

Peter Robinson (58:17):

Condi?

Condoleezza Rice (58:17):

I think George would be excited by this moment, understanding that it was a challenging moment, but he always saw opportunity. Ultimately, he was an optimist. He believed things could be solved. If you kept at the core, the principles on which the United States was founded. There's a story that when George would swear in as Secretary of State ambassadors, he would go to a big globe. He would say to the about to be ambassador, "Show me your country." That person would point to Brazil or to Paraguay or to Kenya. George would say, "No, no. This is your country," and he would point to the United States of America, because the one lesson that I think he would want us all to remember is that since the war, and remember George was a young Marine in that war.

(59:16)

He was part of the greatest generation that fought and won first the war against Naziism and later on the war against communism. George would want, I think, us to remember that central to essentially eight plus decades of relative peace and relative prosperity, if we think about what had come before, the United States was central to that. The United States was central to it because it was founded on the right principles. It worked through its problems like segregation. It worked through issues and came to the right answers on how to stimulate the private sector without wage and price controls. He just had an unfailing belief in this country. I think he would say, "Garden with your allies. They're important, but never think that anything good is going to happen if the United States of America withdraws."

Peter Robinson (01:00:15):

Last question. I see some Stanford students here. They didn't know George. They were born after the Soviet Union became defunct. As a matter of fact, we might as well have been talking about the Grover Cleveland Administration as far as they're concerned. Can you sum up just in one, give me one sentence that they need to understand about George Shultz? Mike?

Mike Boskin (01:00:41):

That you can serve with integrity in anything you do, whether that's in public life, in the business world, in a think tank, in academe, you can serve with integrity, try to do the best you can and try to make sure that you take your God-given skills and make the most of them. You only have one shot at it.

Peter Robinson (01:01:00):

Jay?

Jerome Powell (01:01:01):

Yeah. I think the things that he accomplished were hugely beneficial to this country. We can all be grateful for that. Those of you who are students and looking ahead, you should… I would hope people would look at him as an example and think, "I'd like to do public service. I'd like to serve this great country and make my own contribution."

Peter Robinson (01:01:21):

Condi?

Condoleezza Rice (01:01:22):

I would say to my students, you want to participate in this democracy, you want to participate in the solution of its problems. It's an obligation. It's a privilege to do so, but George Shultz would have probably said, "First know something about the problems you're trying to solve."

Mike Boskin (01:01:41):

For sure. [inaudible 01:01:42]-

Peter Robinson (01:01:42):

Michael Boskin, Condoleezza Rice-

Mike Boskin (01:01:44):

That's perfect.

Peter Robinson (01:01:44):

… and Jay Powell. Thank you.

Jerome Powell (01:01:44):

Thank you.

Mike Boskin (01:01:45):

Thank you.

Jerome Powell (01:01:46):

Thanks [inaudible 01:01:47]. Thanks, Peter.

Peter Robinson (01:01:55):

Jay.

Jerome Powell (01:01:56):

Pleasure. A real pleasure.

Peter Robinson (01:01:57):

Thank you so much.

Mike Boskin (01:01:58):

That was terrific.

Peter Robinson (01:01:59):

[inaudible 01:01:59]-

Mike Boskin (01:01:59):

Thank you.

Peter Robinson (01:02:00):

Great. We'll see [inaudible 01:02:01]-

Peter Robinson (01:02:00):

Kevin. Jay, these are the men who'd like to have their picture with you-

Jerome Powell (01:02:05):

Okay.

Peter Robinson (01:02:06):

… if you don't mind.