Rev’s Transcript Library

Explore our extensive collection of free transcripts from political figures and public events. Journalists, students, researchers, and the general public can explore transcripts of speeches, debates, congressional hearings, press conferences, interviews, podcasts, and more.

Crew-12 Mission Leaders Speak on Space Station Launch

NASA’s SpaceX Crew-12 mission leadership discusses final launch and mission preparations for the International Space Station. Read the transcript here.

Real ID Press Conference

Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem holds a press conference on Real ID. Read the transcript here.

DOJ Epstein Files Press Conference

Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche holds a press conference on the release of new Epstein files. Read the transcript here.

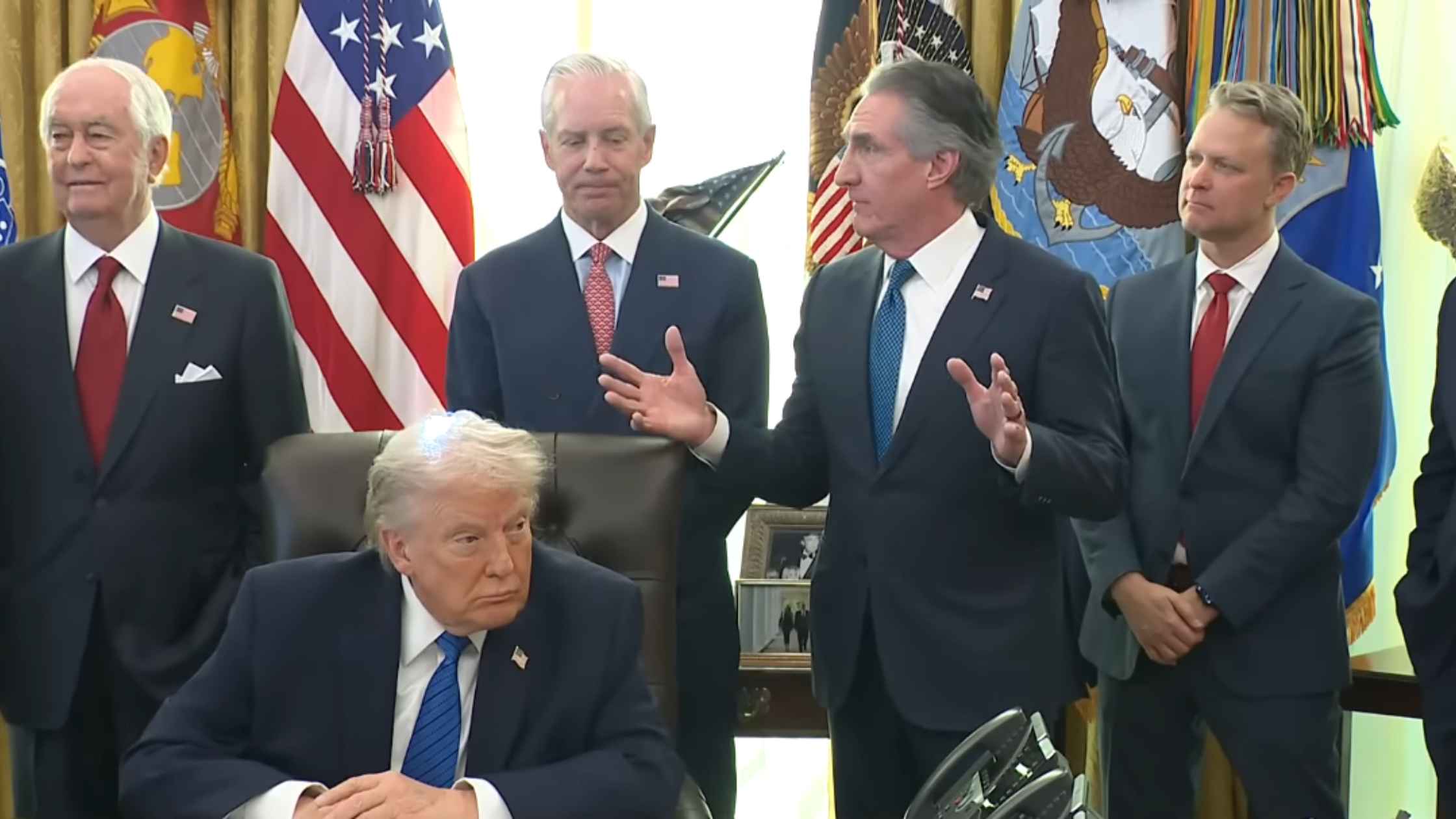

Cabinet Meeting 1/29/26

Donald Trump holds a cabinet meeting with several members from his administration on 1/29/26. Read the transcript here.

Kid Rock Testifies Before The Senate Commerce Committee

Kid Rock gives testimony in the Senate Ticketmaster hearing calling to end concert ticket price gouging. Read the transcript here.

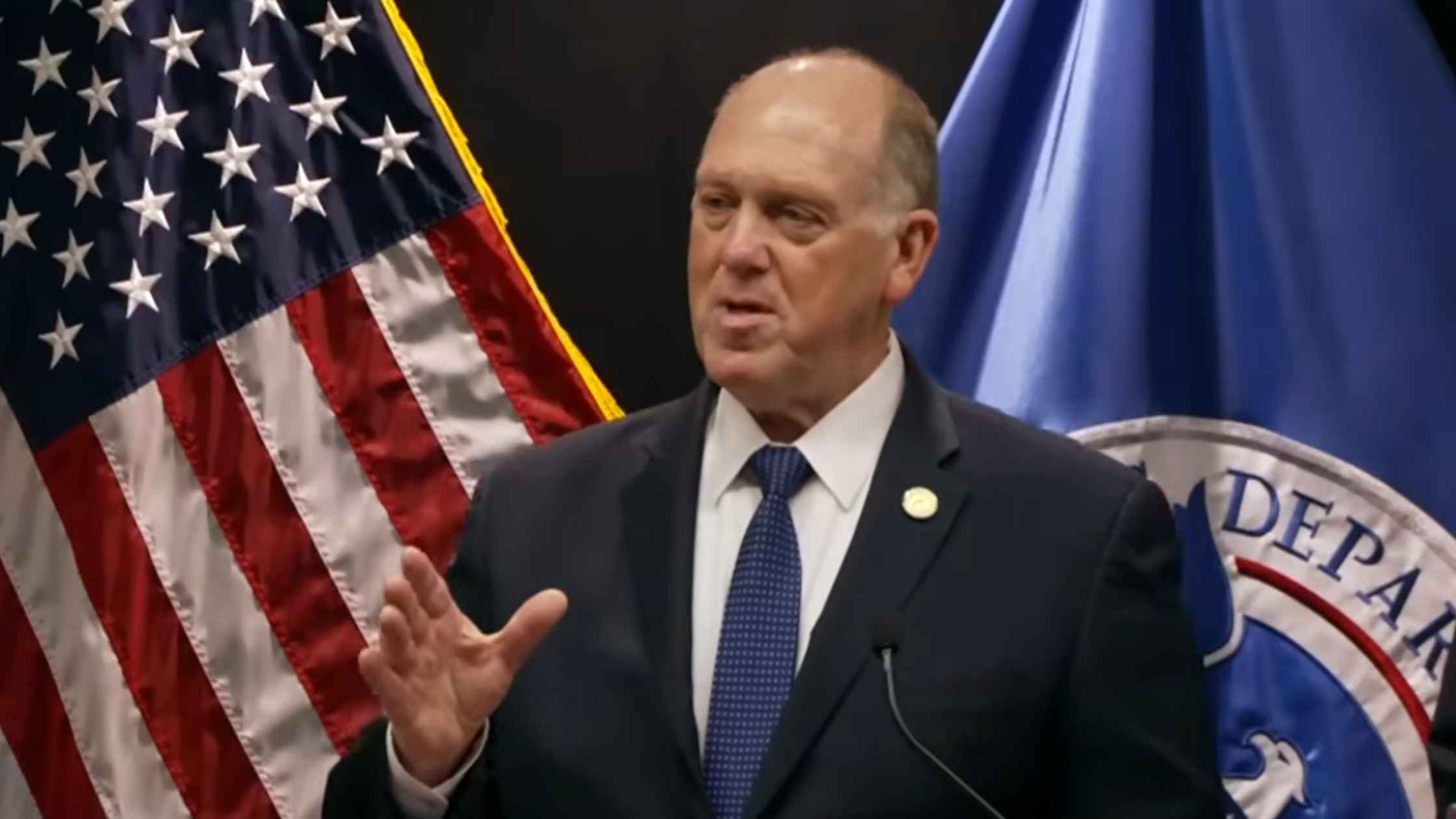

Tom Homan Press Conference

Border czar Tom Homan holds a news conference in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Read the transcript here.

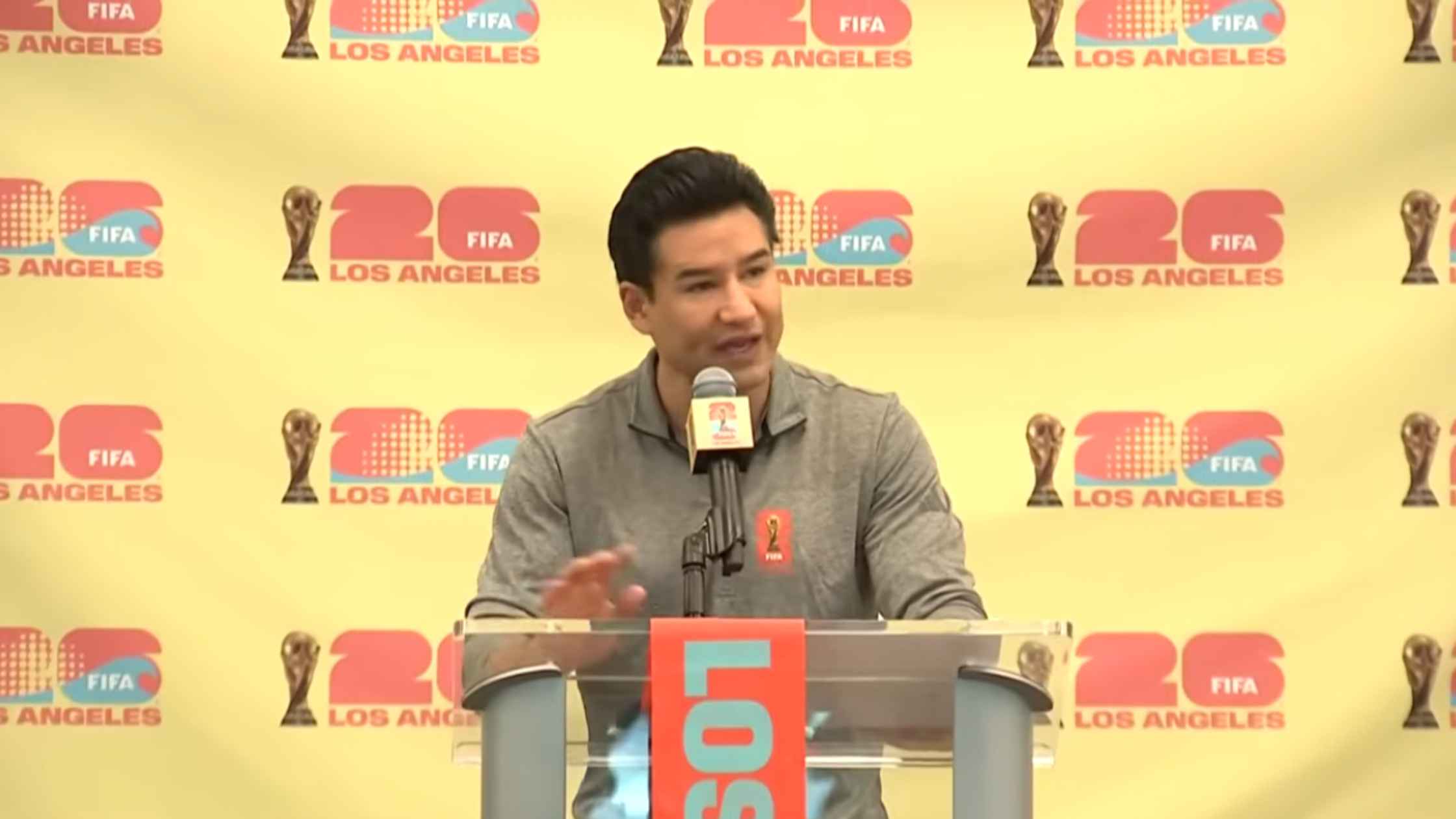

World Cup Update

The World Cup Committee unveils community and fan engagement plans for the tournament. Read the transcript here.

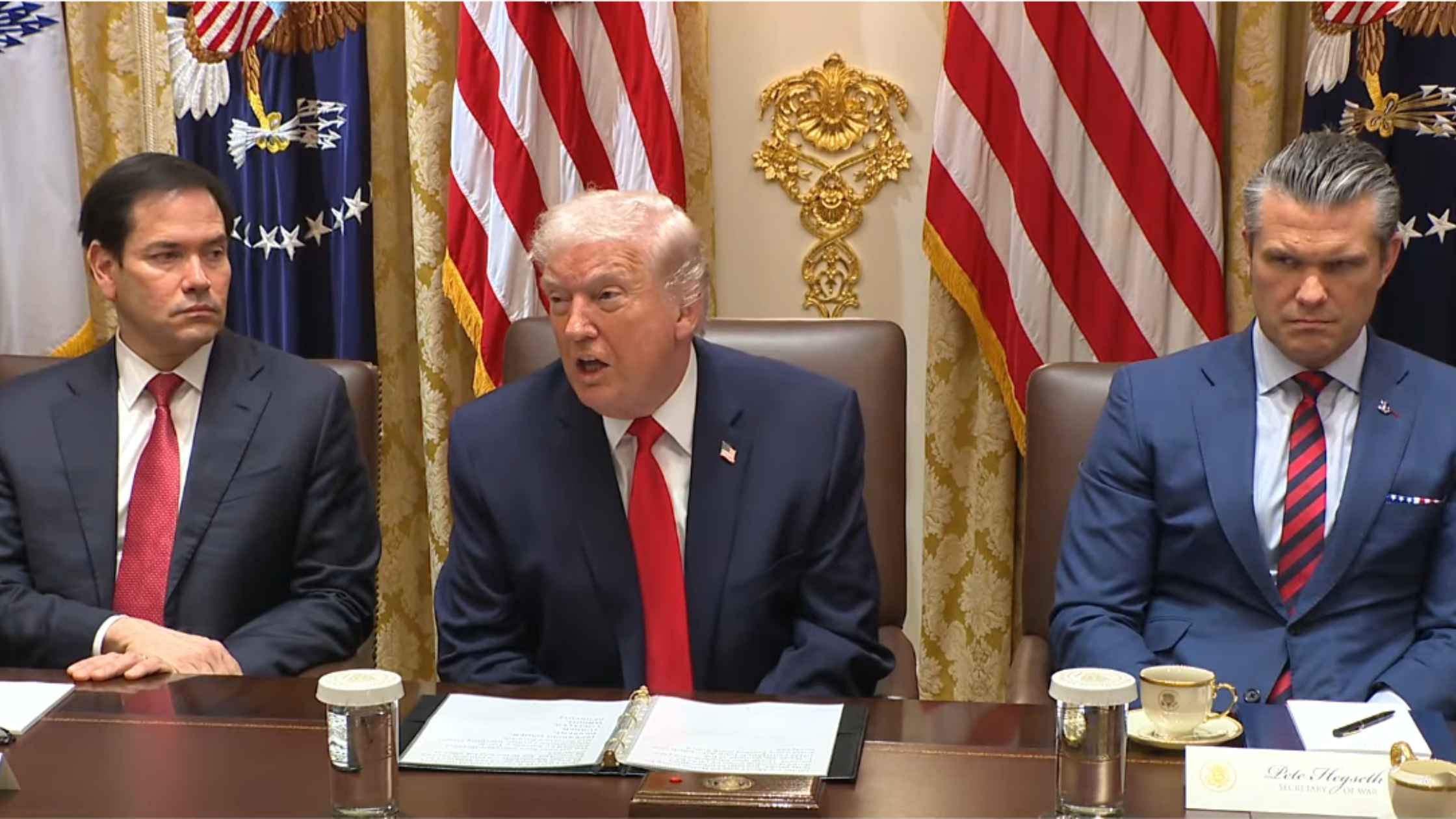

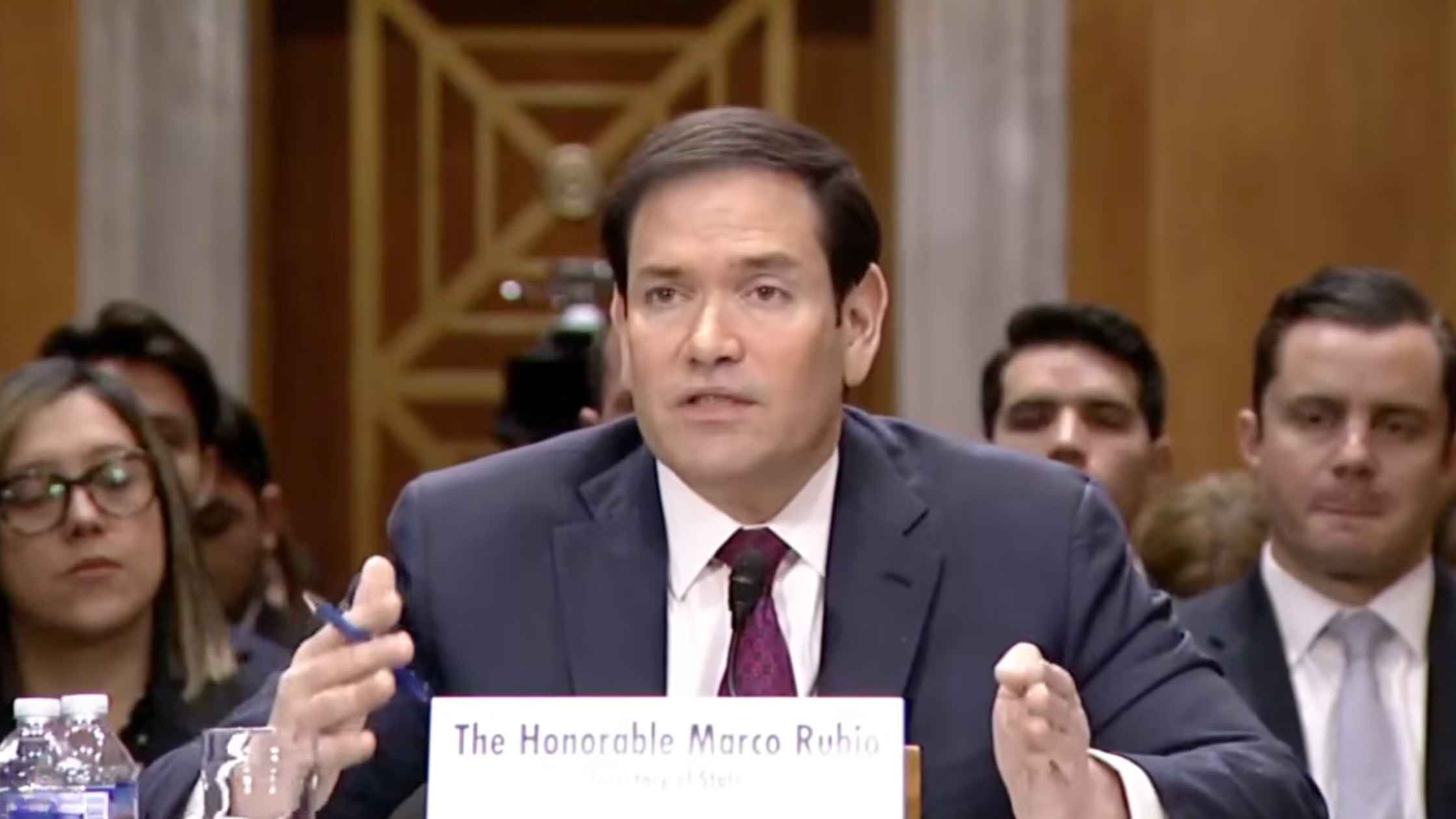

Venezuela Policy Congressional Hearing

Marco Rubio testifies at a Senate hearing on U.S. policy toward Venezuela. Read the transcript here.

Subscribe to The Rev Blog

Sign up to get Rev content delivered straight to your inbox.