Rev’s Transcript Library

Explore our extensive collection of free transcripts from political figures and public events. Journalists, students, researchers, and the general public can explore transcripts of speeches, debates, congressional hearings, press conferences, interviews, podcasts, and more.

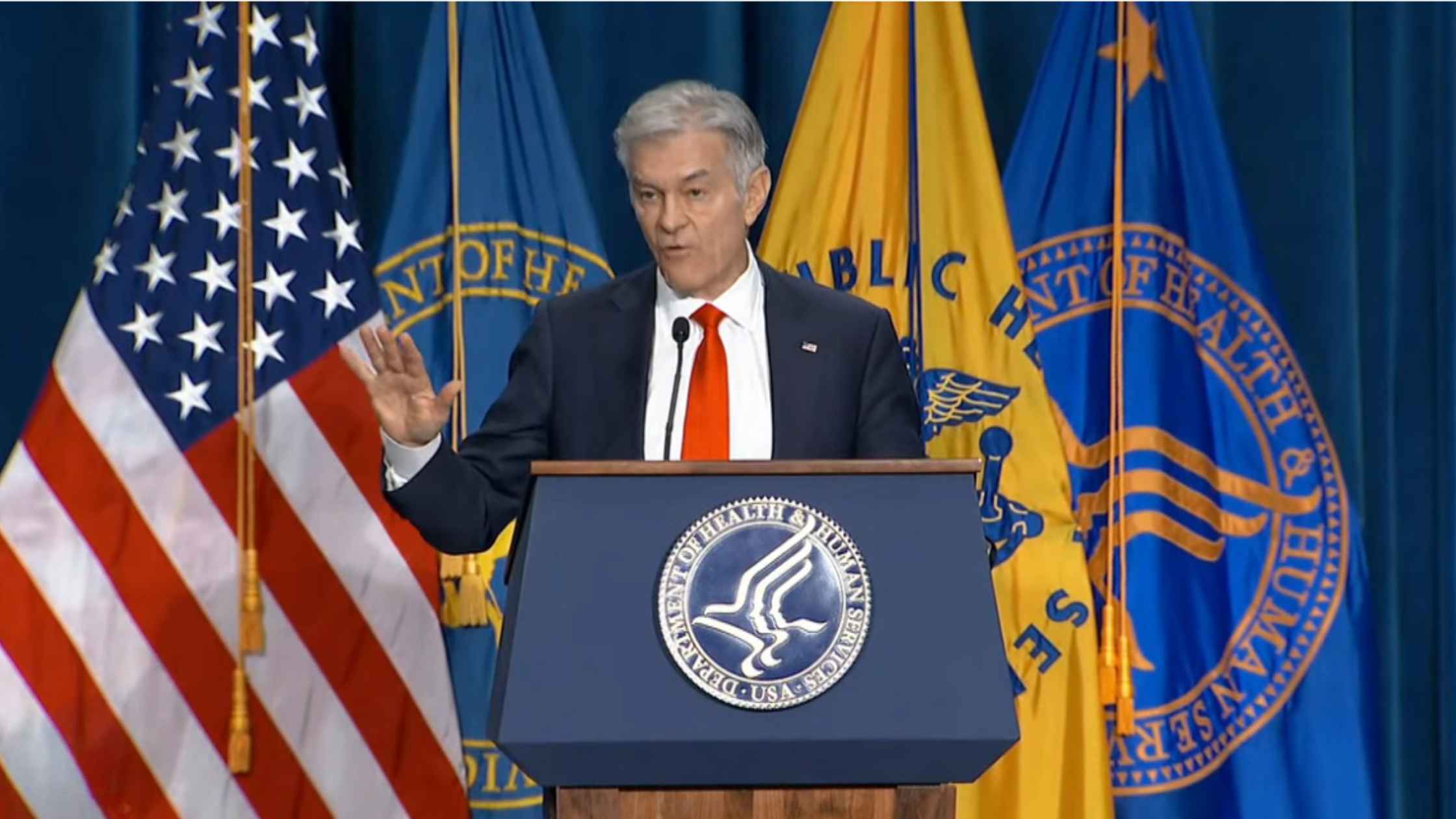

Restrictions On Gender-Affirming Care For Minors

Health Secretary RFK Jr. and Dr. Oz unveil new restrictions on gender identity care for minors. Read the transcript here.

Hearing on Artificial Intelligence

House Homeland Security Committee hearing on artificial intelligence. Read the transcript here.

FCC Oversight Hearing

Senate FCC oversight hearing with FCC chair Brendan Carr. Read the transcript here.

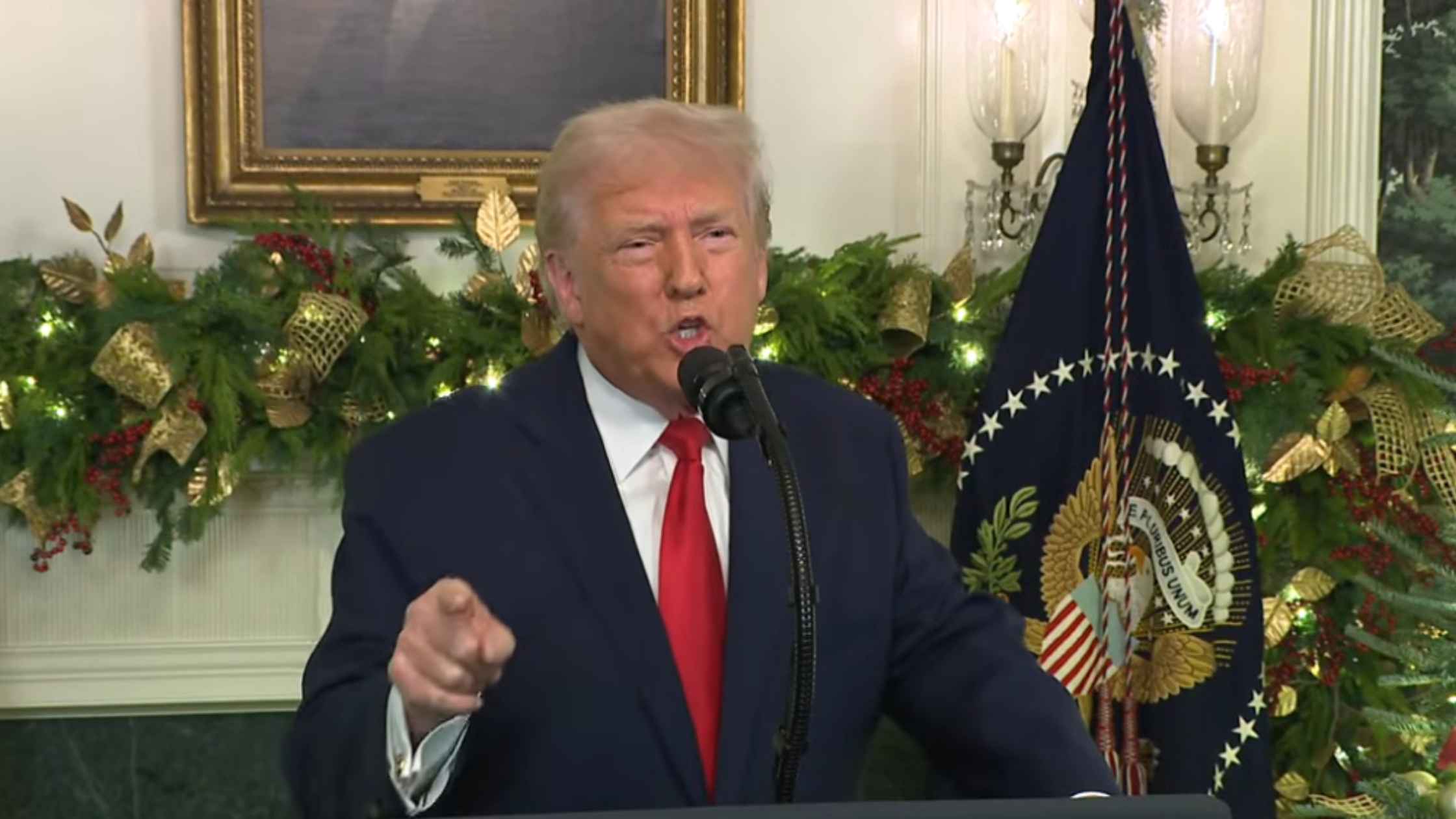

Presidential Address on 12/17/25

Donald Trump gives a Primetime address on 12/17/25. Read the transcript here.

White House Hanukkah Celebration

Donald Trump hosts a Hanukkah celebration at White House. Read the transcript here.

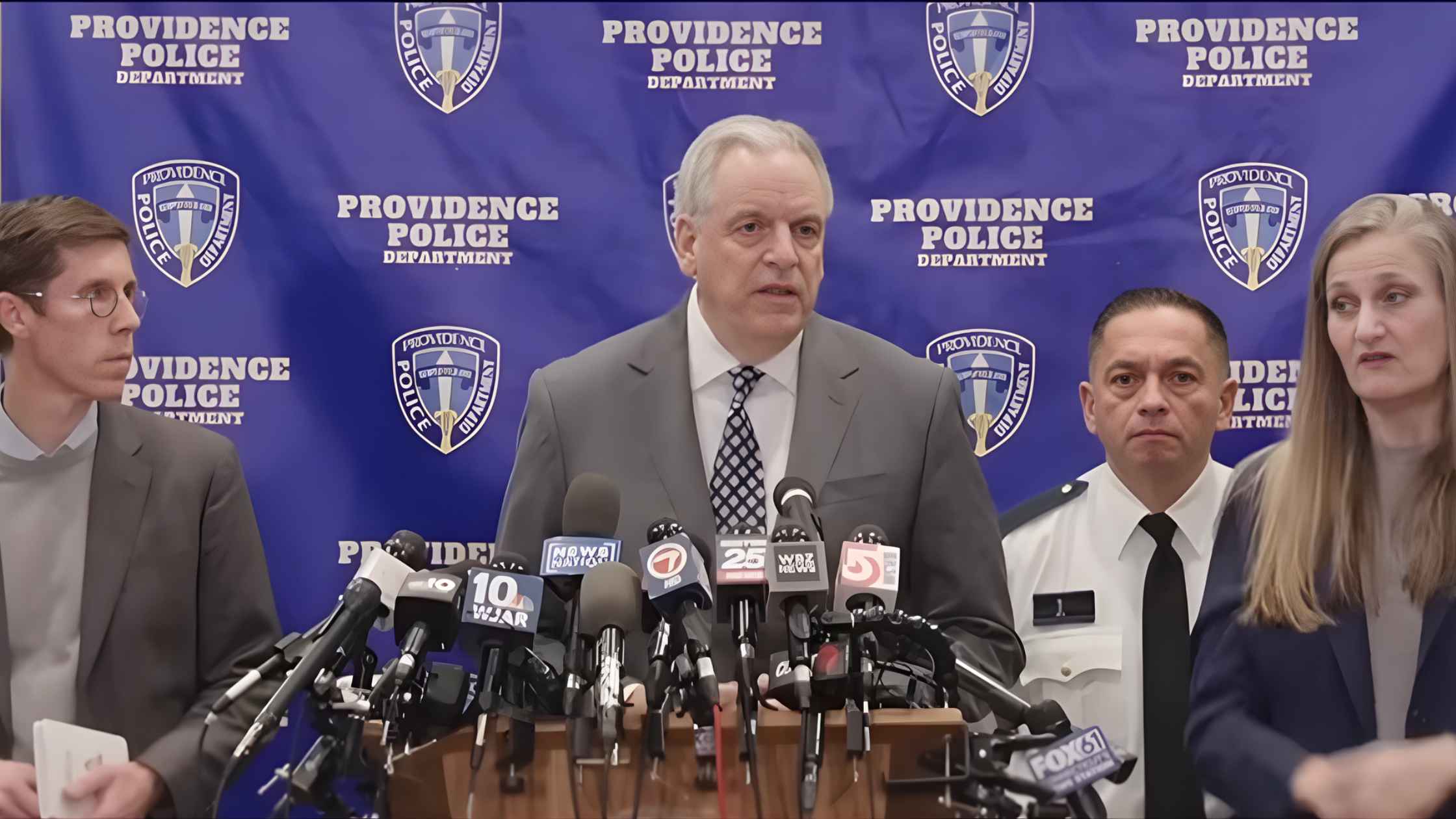

Brown Shooting Update 12/16/25

Officials hold a press briefing on the shooting at Brown University on 12/16/25. Read the transcript here.

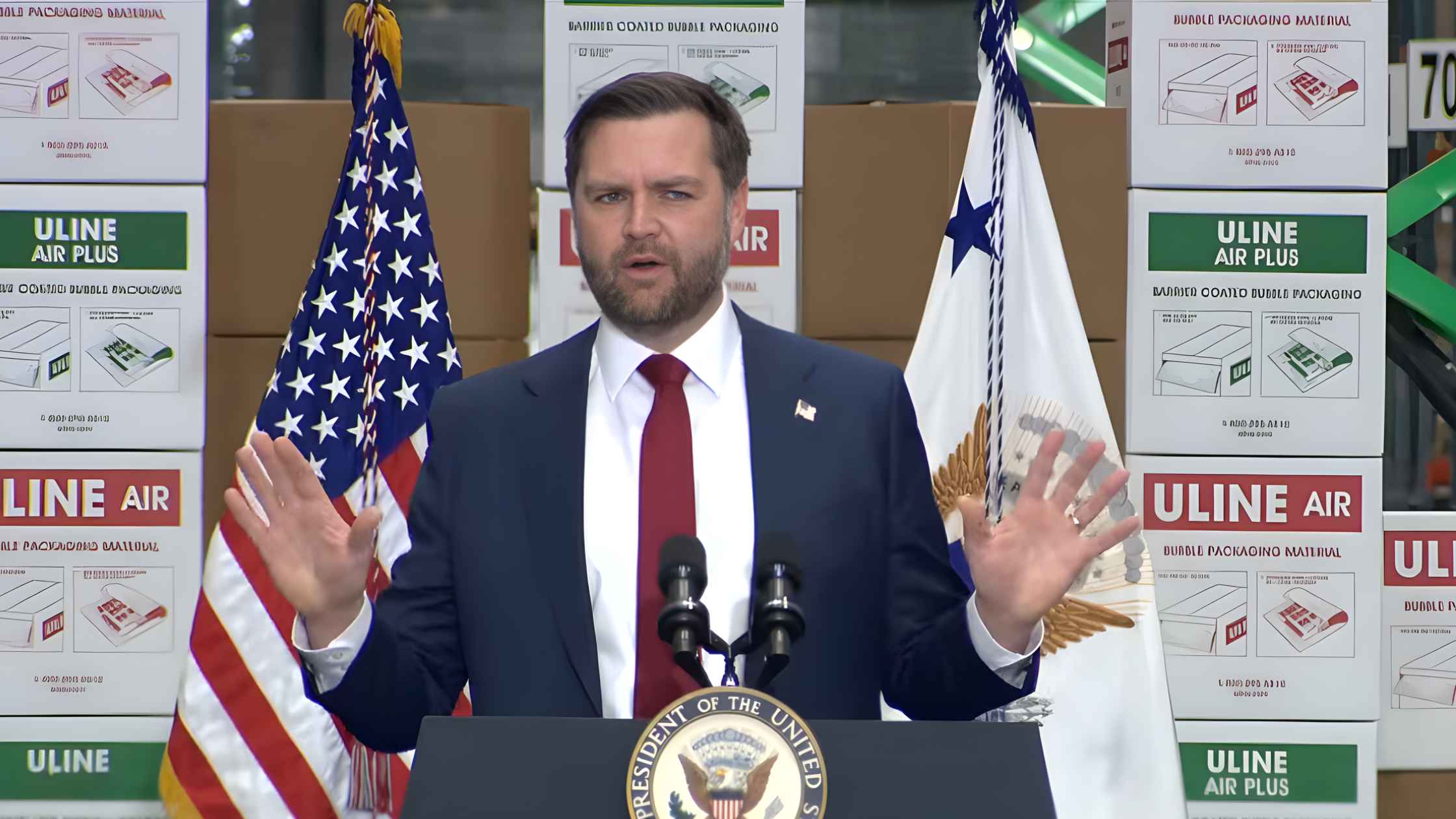

J.D. Vance Speaks in Pennsylvania

J.D. Vance delivers a speech in Allentown, PA, highlighting Donald Trump's economic agenda. Read the transcript here.

Reiner Killing Update

LA County District Attorney Nathan J. Hochman and Chief of the LA Police Department Jim McDonnell give an update on the Reiner killings. Read the transcript here.

Remembering Rob Reiner

A look back at the life and work of acclaimed film director and actor Rob Reiner. Read the transcript here.

Subscribe to The Rev Blog

Sign up to get Rev content delivered straight to your inbox.