Rev’s Transcript Library

Explore our extensive collection of free transcripts from political figures and public events. Journalists, students, researchers, and the general public can explore transcripts of speeches, debates, congressional hearings, press conferences, interviews, podcasts, and more.

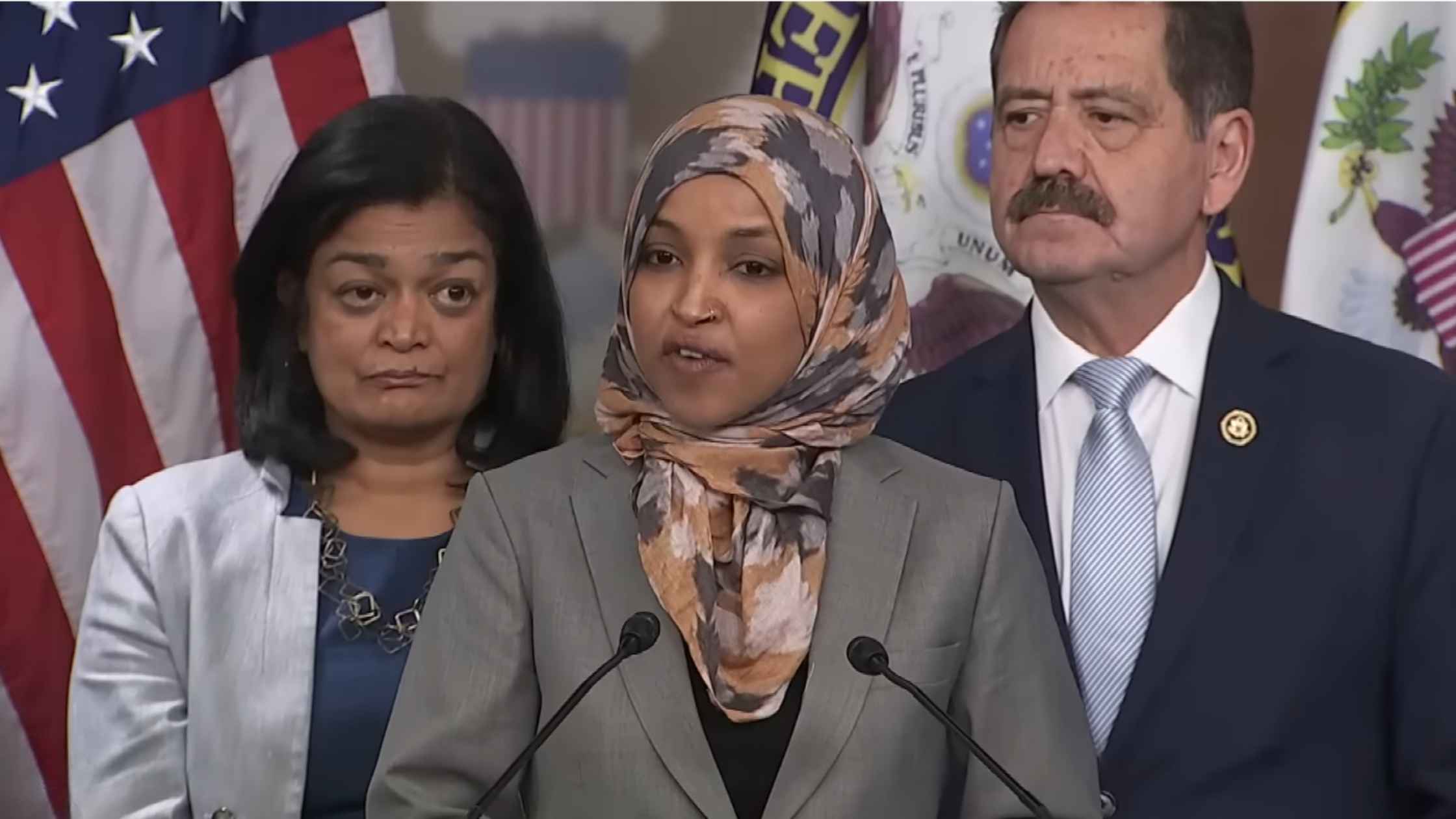

CPC speaks on DHS

Ilhan Omar and members of the Congressional Progressive Caucus hold a press conference on DHS funding and reform. Read the transcript here.

Greenland Mineral Resouce Minister Press Conference

Greenland's Mineral Resources Minister Naaja Nathanielsen speaks ahead of a meeting with JD Vance and Secretary of State Marco Rubio. Read the transcript here.

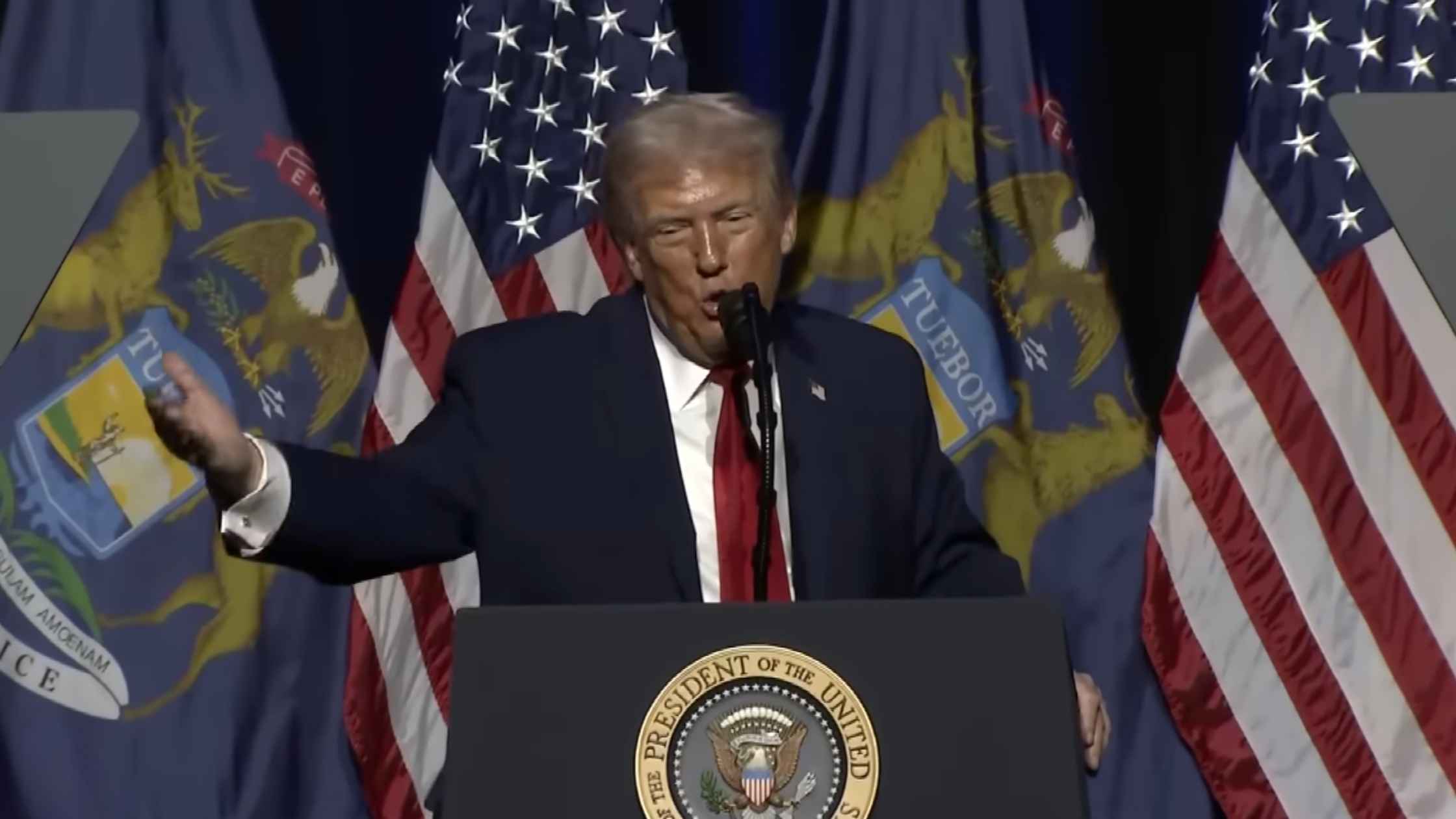

Trump at the Detroit Economic Club

Donald Trump delivers remarks at the Detroit Economic Club in Detroit, Michigan. Read the transcript here.

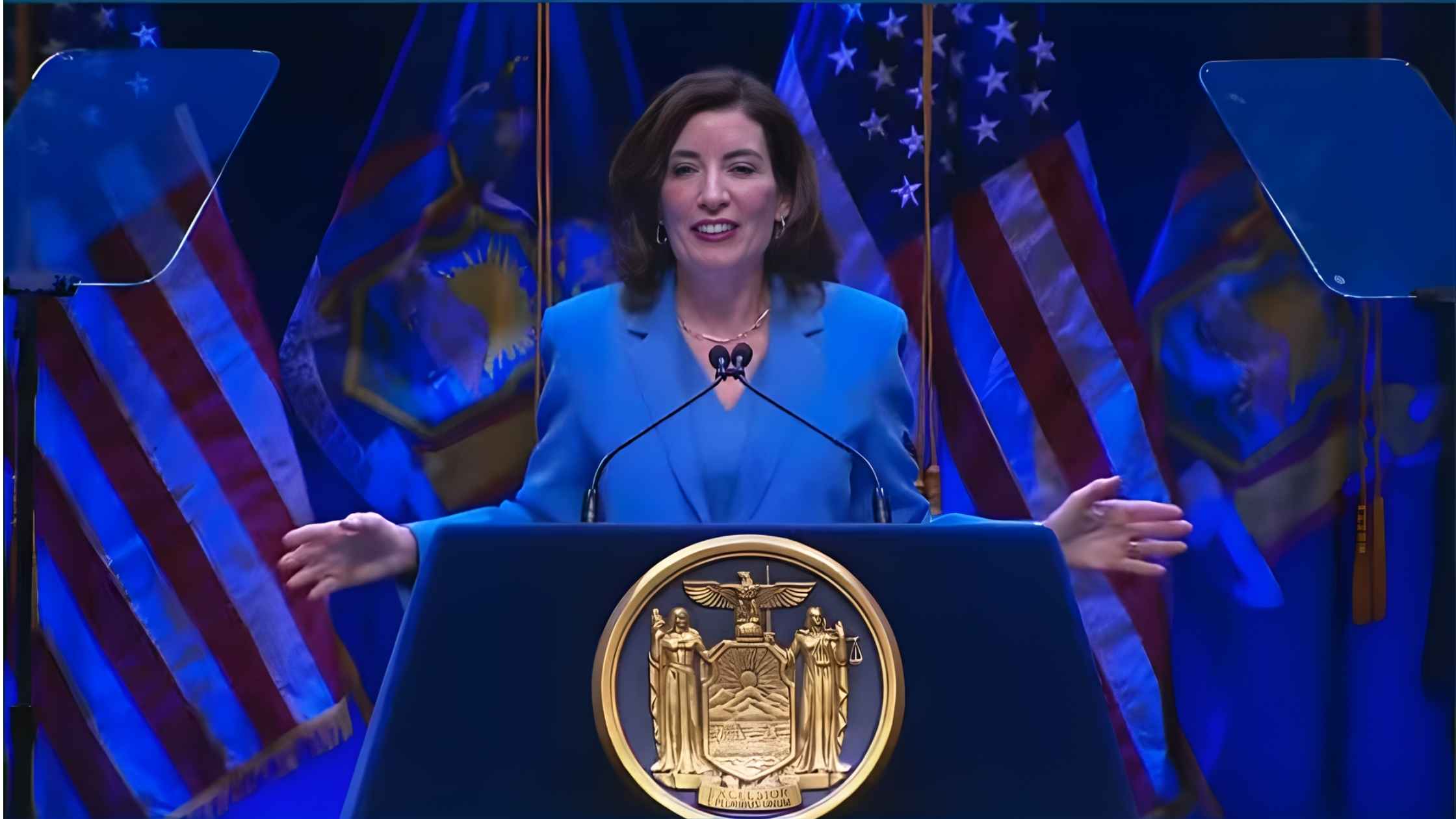

NY State of the State Address

New York Governor Kathy Hochul delivers the State of the State address on 1/13/26. Read the transcript here.

Supreme Court Hearing on Transgender Students Sports Bans

The Supreme Court hears arguments on whether states can ban transgender students from sports. Read the transcript here.

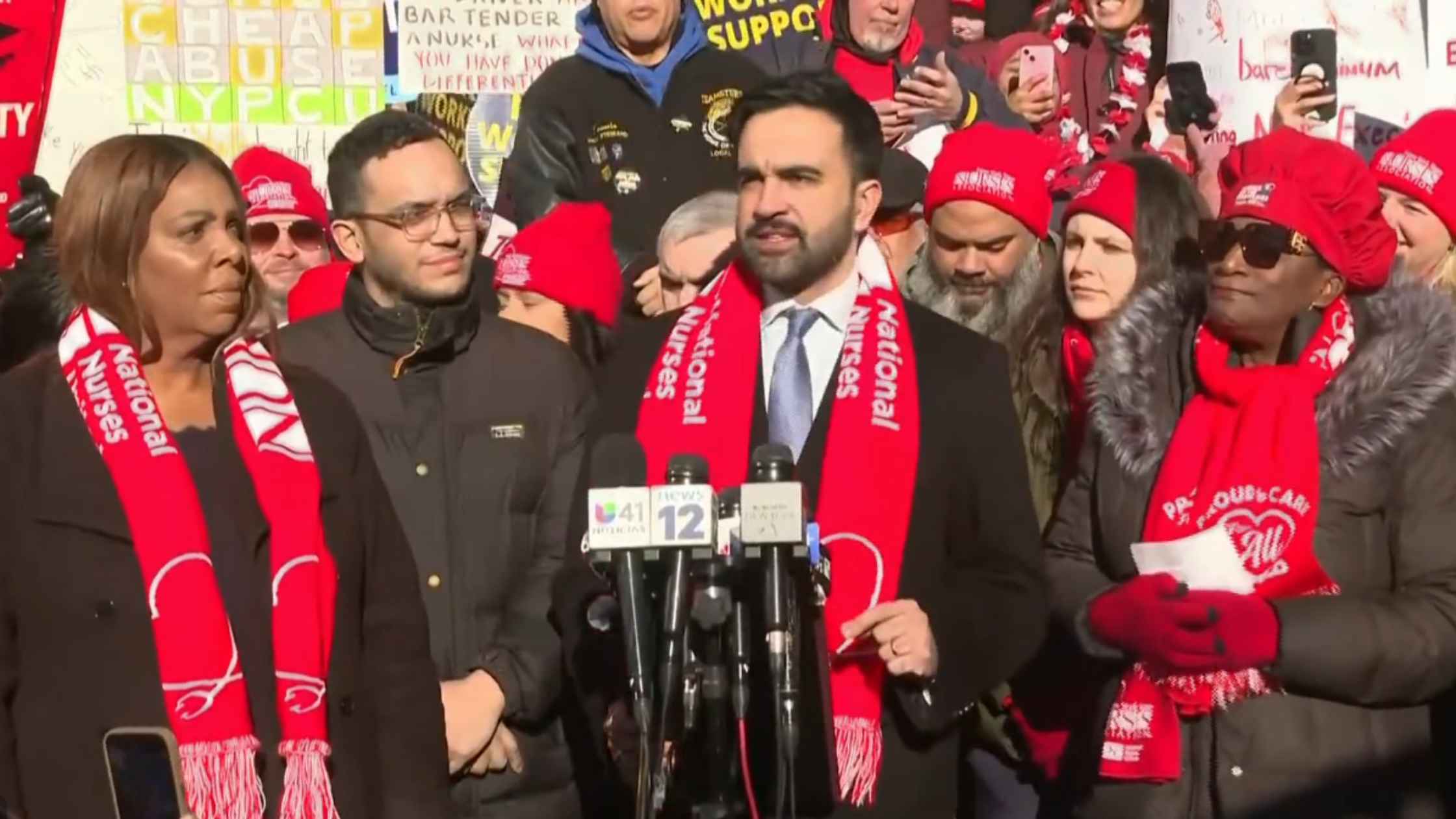

Nurse Strike Press Conference

A press conference was held as thousands of nurses at several major New York City hospitals went on strike. Read the transcript here.

U.N. Humanitarian Briefing

The United Nations hold a briefing in Geneva on humanitarian crises in the world. Read the transcript here.

Hegseth Speaks at SpaceX

Secretary of War Pete Hegseth and SpaceX founder Elon Musk speak at the SpaceX headquarters in Brownsville, Texas. Read the transcript here.

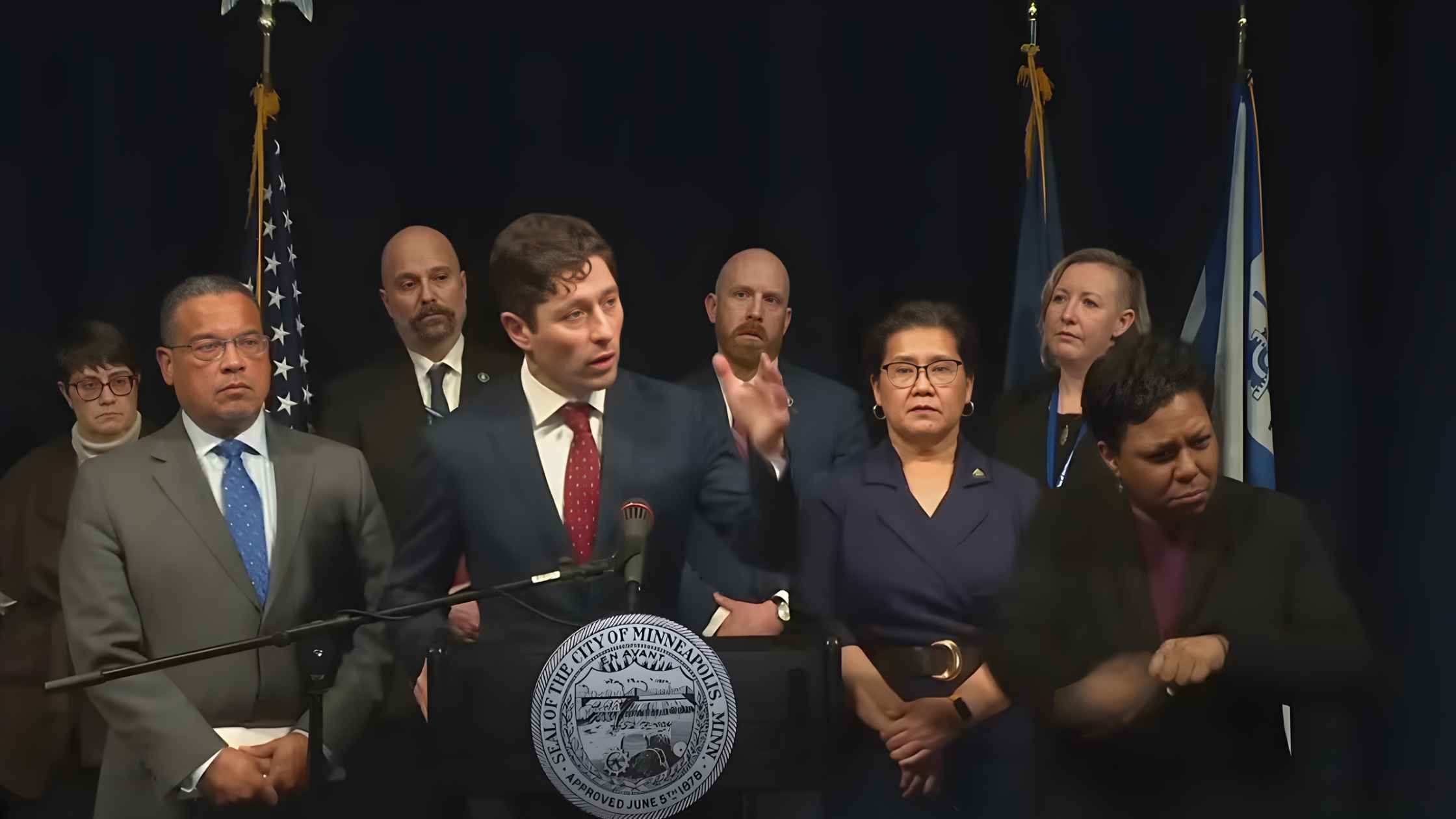

Minnesota Attorney General Press Conference

AG Keith Ellison holds a briefing, along with Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey, after the state filed a lawsuit against Kristi Noem. Read the transcript here.

Subscribe to The Rev Blog

Sign up to get Rev content delivered straight to your inbox.