Rev’s Transcript Library

Explore our extensive collection of free transcripts from political figures and public events. Journalists, students, researchers, and the general public can explore transcripts of speeches, debates, congressional hearings, press conferences, interviews, podcasts, and more.

Human Rights Watch Annual World Report

Human Rights Watch releases its annual World Report documenting the state of human rights in more than 100 countries. Read the transcript here.

Border Wall Press Conference

Secretary of Homeland Defense Kristi Noem provides an update on the border wall. Read the transcript here.

Homan News Conference in Minneapolis

Tom Homan announces the withdrawal of 700 federal officers from Minnesota. Read the transcript here.

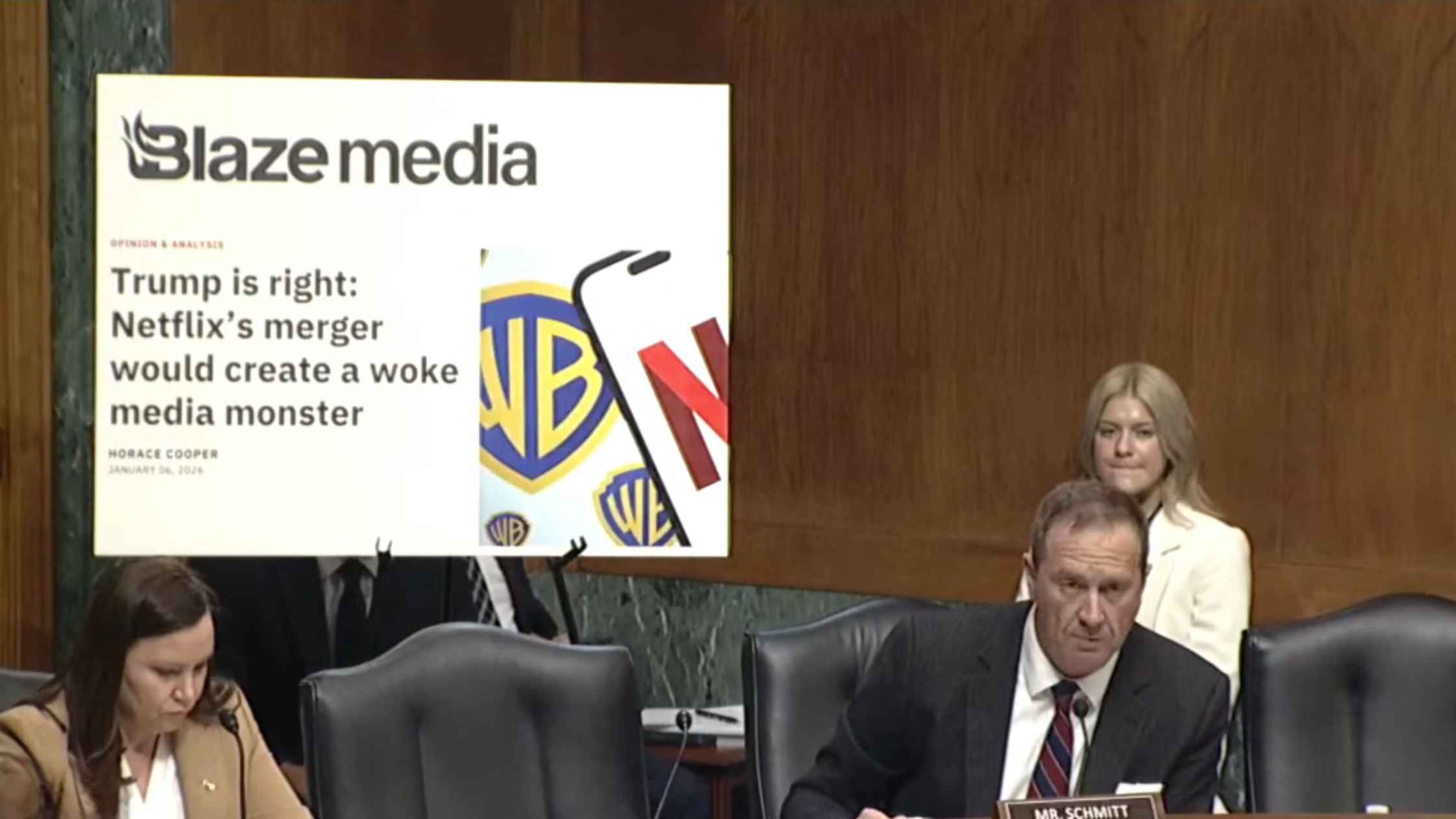

Netflix-Warner Brothers Merger Hearing

Senate Judiciary hearing examines proposed Netflix-Warner Brothers deal. Read the transcript here.

Congressional Testimony on DHS Encounters

Renee Goode's brothers and three U.S. citizens who have had recent violent encounters with DHS testify before Congress. Read the transcript here.

Trump Signs Funding Bill

Donald Trump signs the Consolidated Appropriations Act to open the federal government. Read the transcript here.

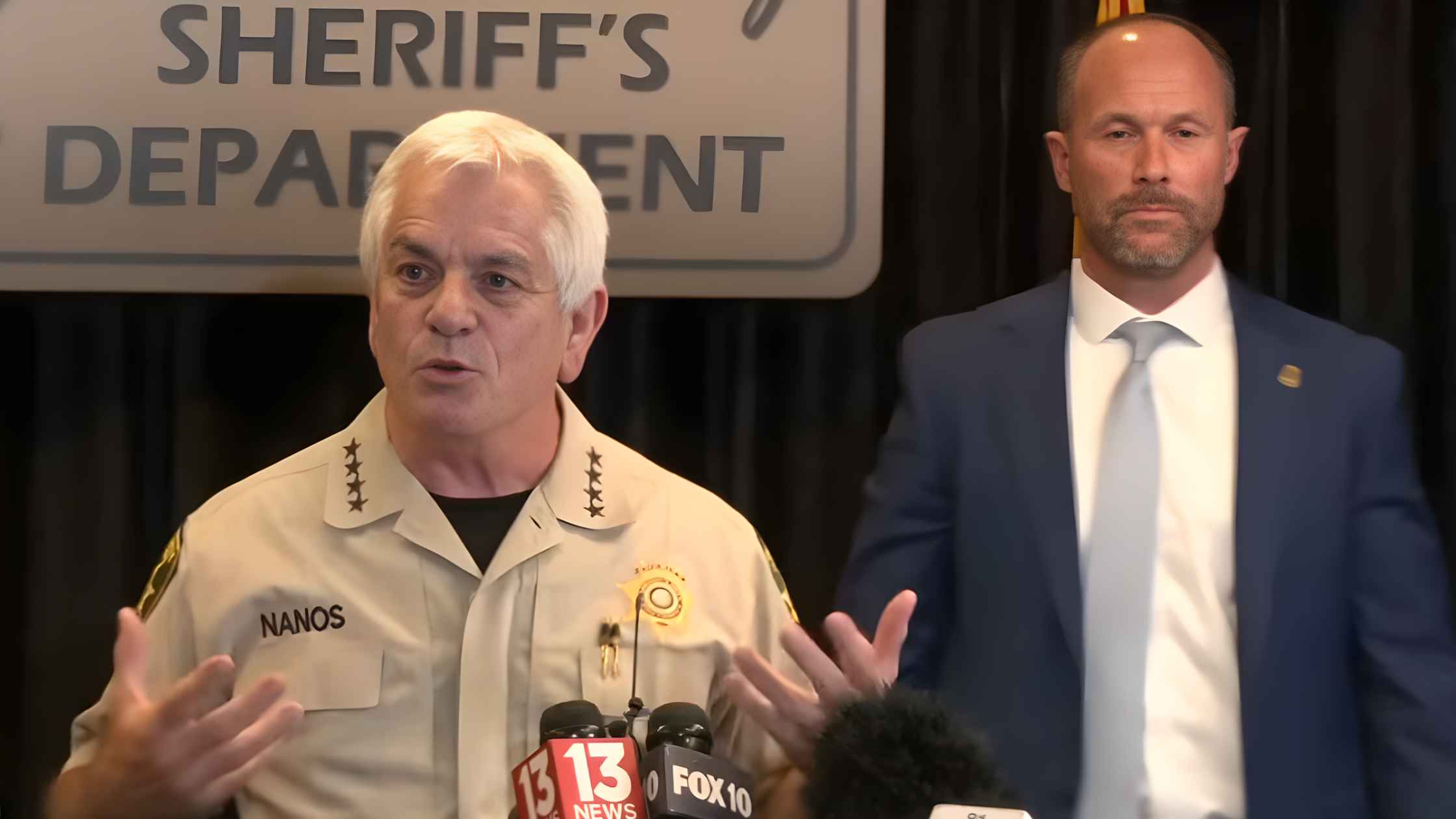

Nancy Guthrie Update

Arizona Pima County Sheriff Chris Nanos gives an update on the ongoing Nancy Guthrie case. Read the transcript here.

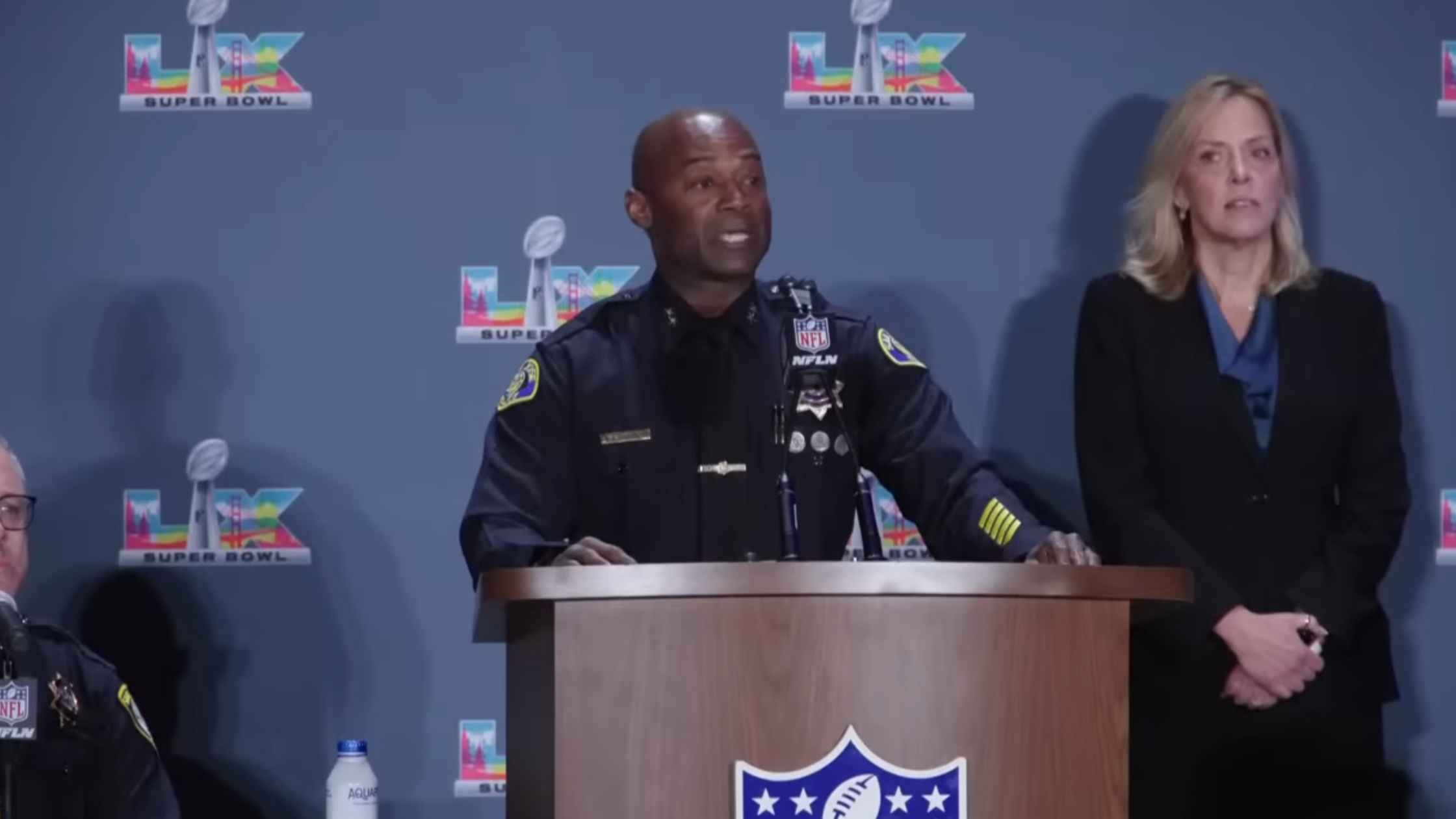

Super Bowl Safety Press Conference

NFL and law enforcement in San Francisco hold a press conference regarding public safety plans for the Super Bowl. Read the transcript here.

U.K. Government Reaction to Epstein Files Release

Chief Secretary to the British PM Darren Jones makes a statement in Parliament after the latest release of the Epstein files. Read the transcript here.

Subscribe to The Rev Blog

Sign up to get Rev content delivered straight to your inbox.