Rev’s Transcript Library

Explore our extensive collection of free transcripts from political figures and public events. Journalists, students, researchers, and the general public can explore transcripts of speeches, debates, congressional hearings, press conferences, interviews, podcasts, and more.

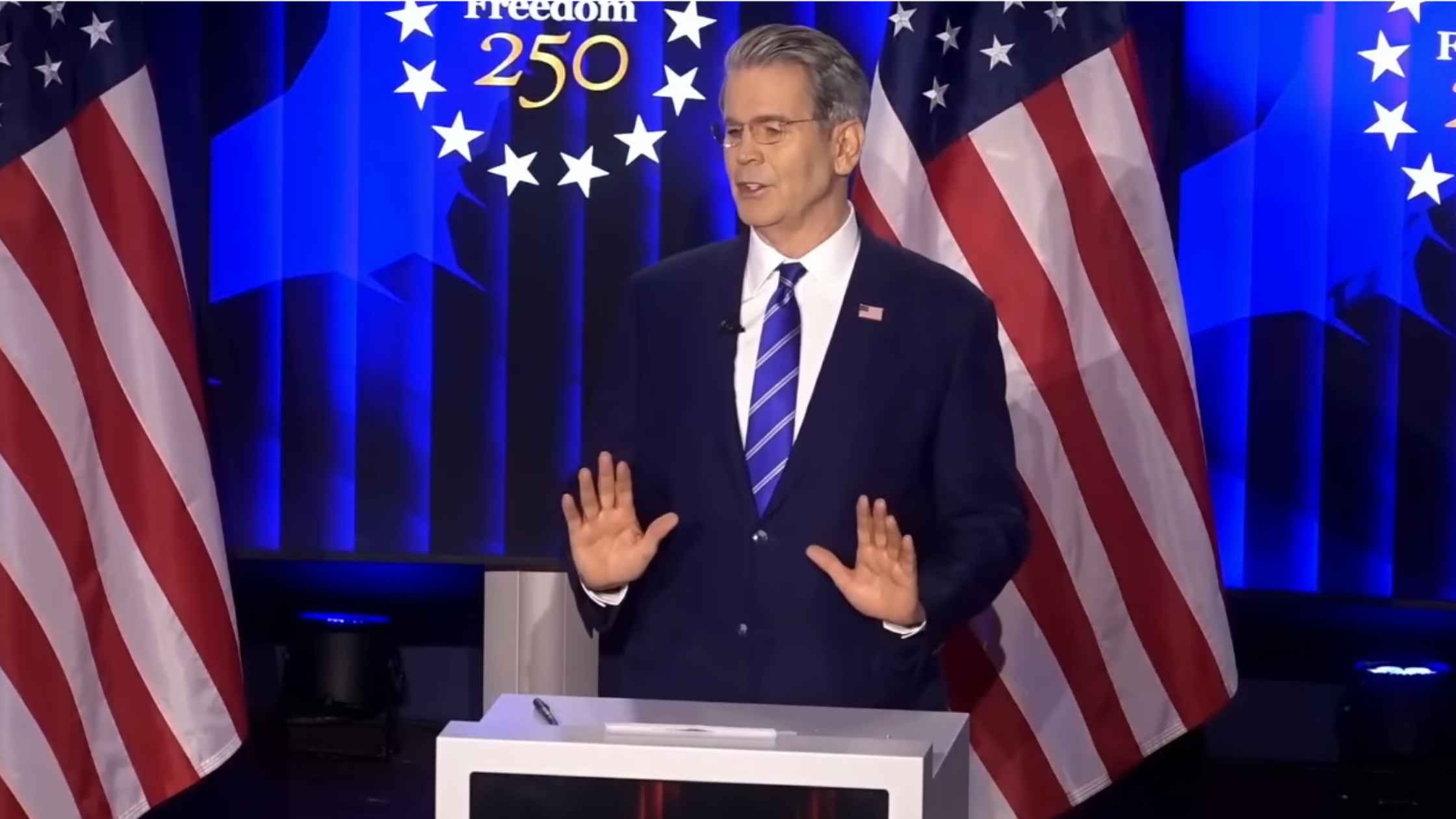

Bessent at Davos

U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent speaks at a news conference in Davos, Switzerland, at the 2026 World Economic Forum. Read the transcript here.

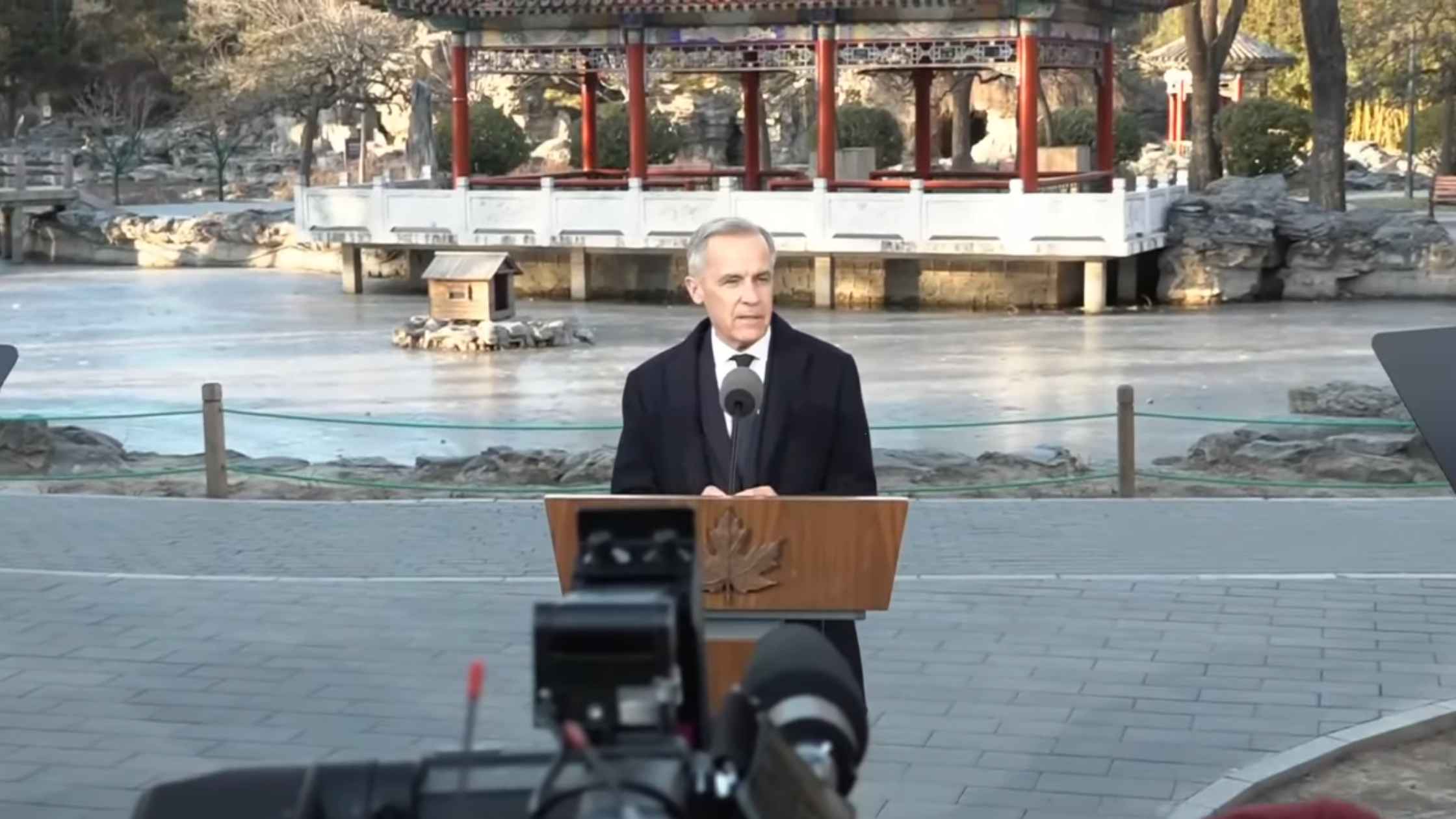

Carney Speaks after Meeting China’s Xi Jinping

Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney speaks to the press in Beijing after meeting with Xi Jinping. Read the transcript here.

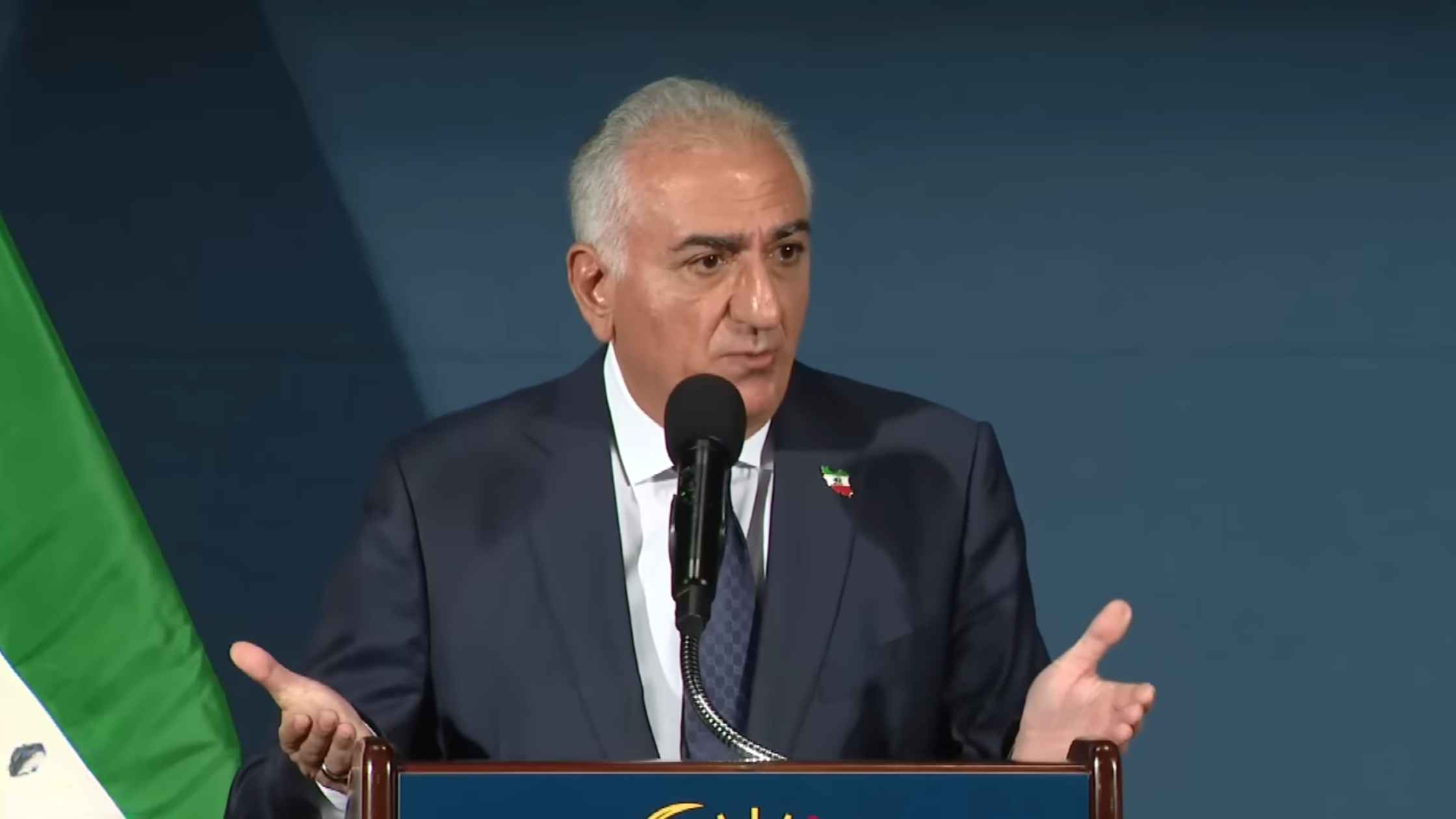

Reza Pahlavi News Conference

Exiled Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi holds a news conference on the future of Iran. Read the transcript here.

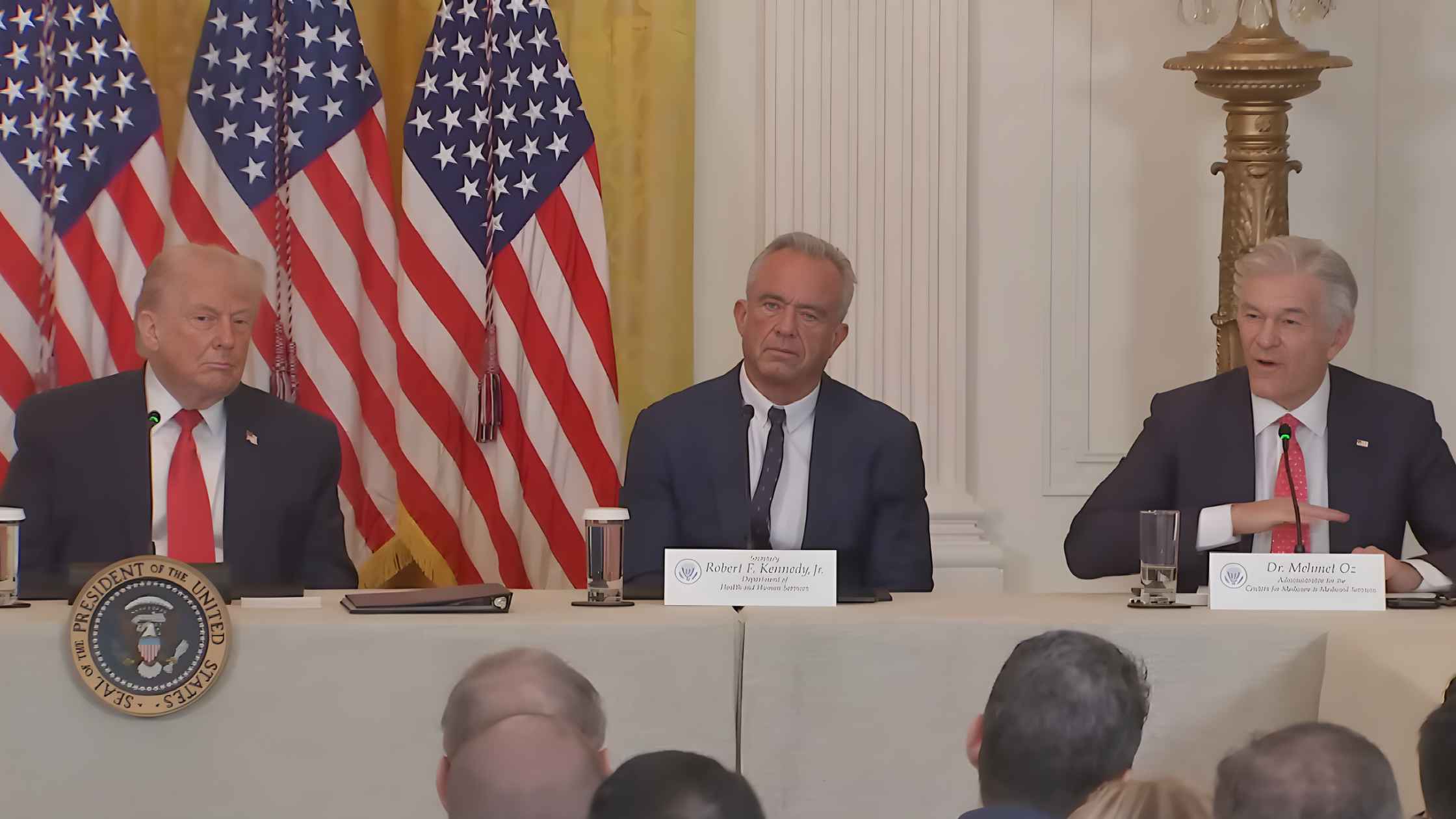

Rural Health Roundtable

Donald Trump takes part in a rural healthcare roundtable alongside RFK Jr., Dr. Oz, and other health officials. Read the transcript here.

Maria Corina Machado Press Conference

Maria Corina Machado holds a press conference after giving her Nobel Peace Prize medal to Donald Trump. Read the transcript here.

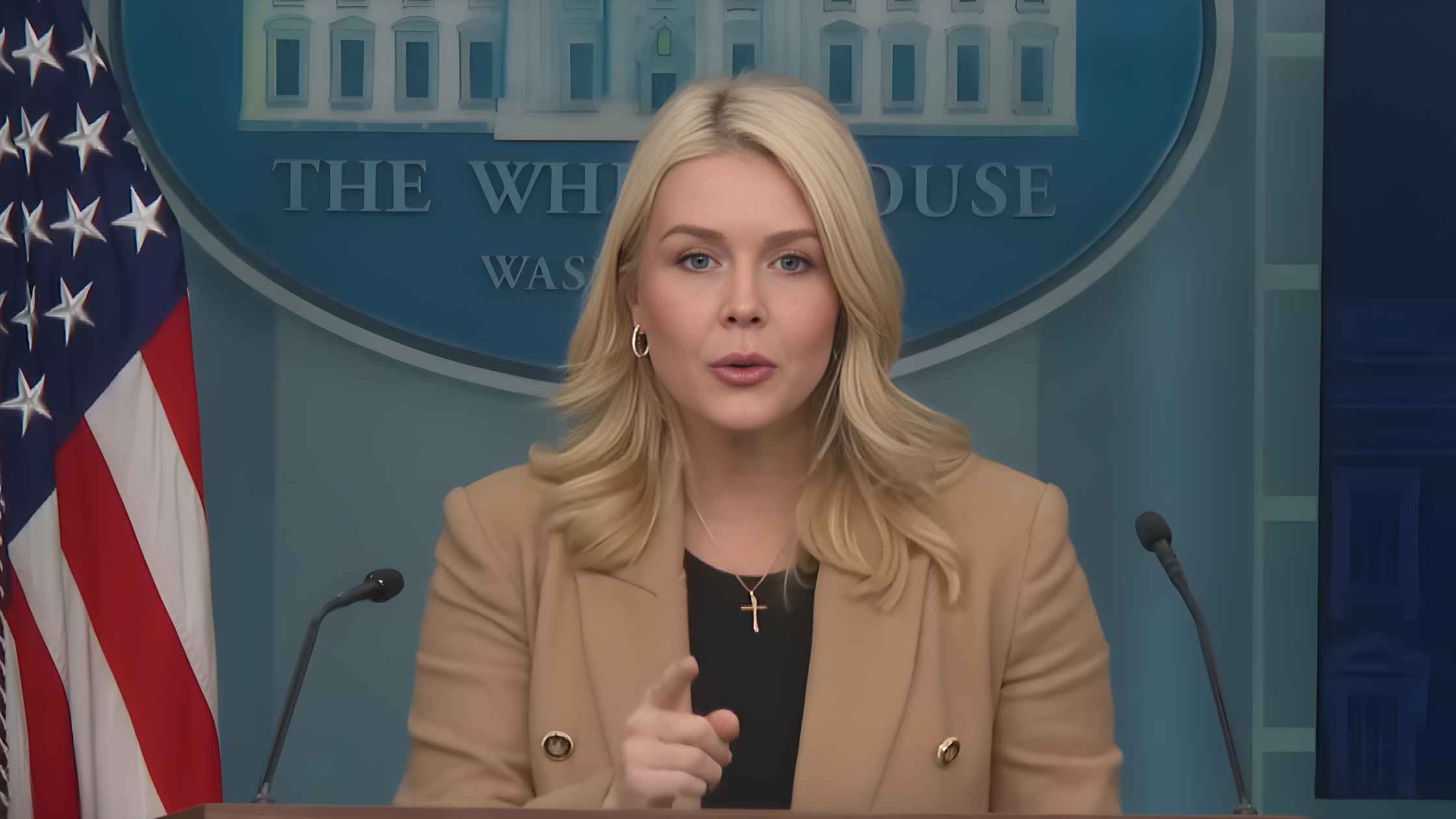

Karoline Leavitt White House Press Briefing on 1/15/26

Karoline Leavitt holds the White House Press Briefing for 1/15/26. Read the transcript here.

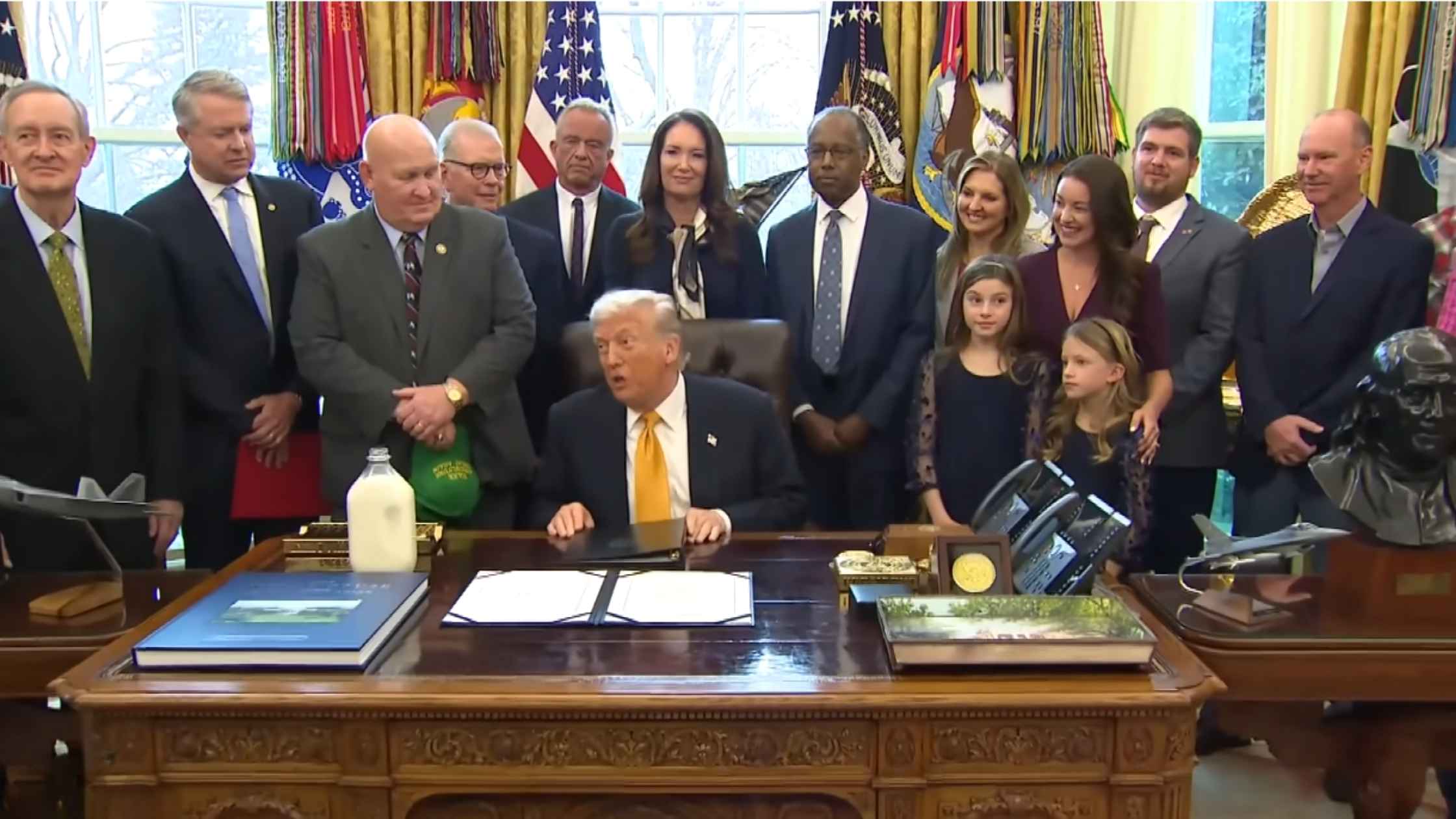

Whole Milk Executive Order

Donald Trump signs the Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act into law. Read the transcript here.

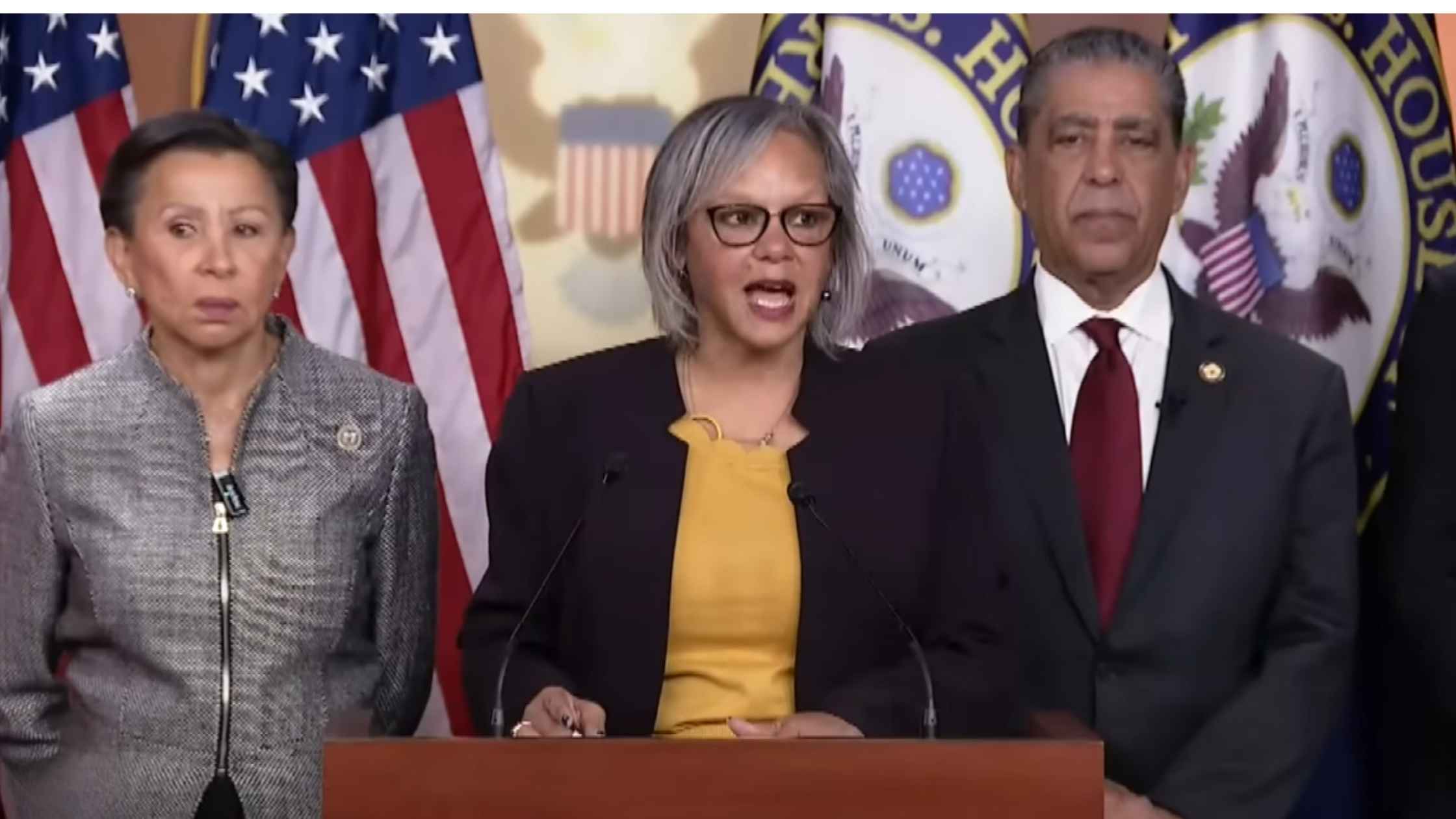

Noem Impeachment Articles

Representative Robin Kelly says she filed articles of impeachment against Kristi Noem. Read the transcript here.

Danish and Greenland Leaders Press Conference

Danish and Greenlandic delegations hold a press conference following talks with their US counterparts. Read the transcript here.

Subscribe to The Rev Blog

Sign up to get Rev content delivered straight to your inbox.