Rev’s Transcript Library

Explore our extensive collection of free transcripts from political figures and public events. Journalists, students, researchers, and the general public can explore transcripts of speeches, debates, congressional hearings, press conferences, interviews, podcasts, and more.

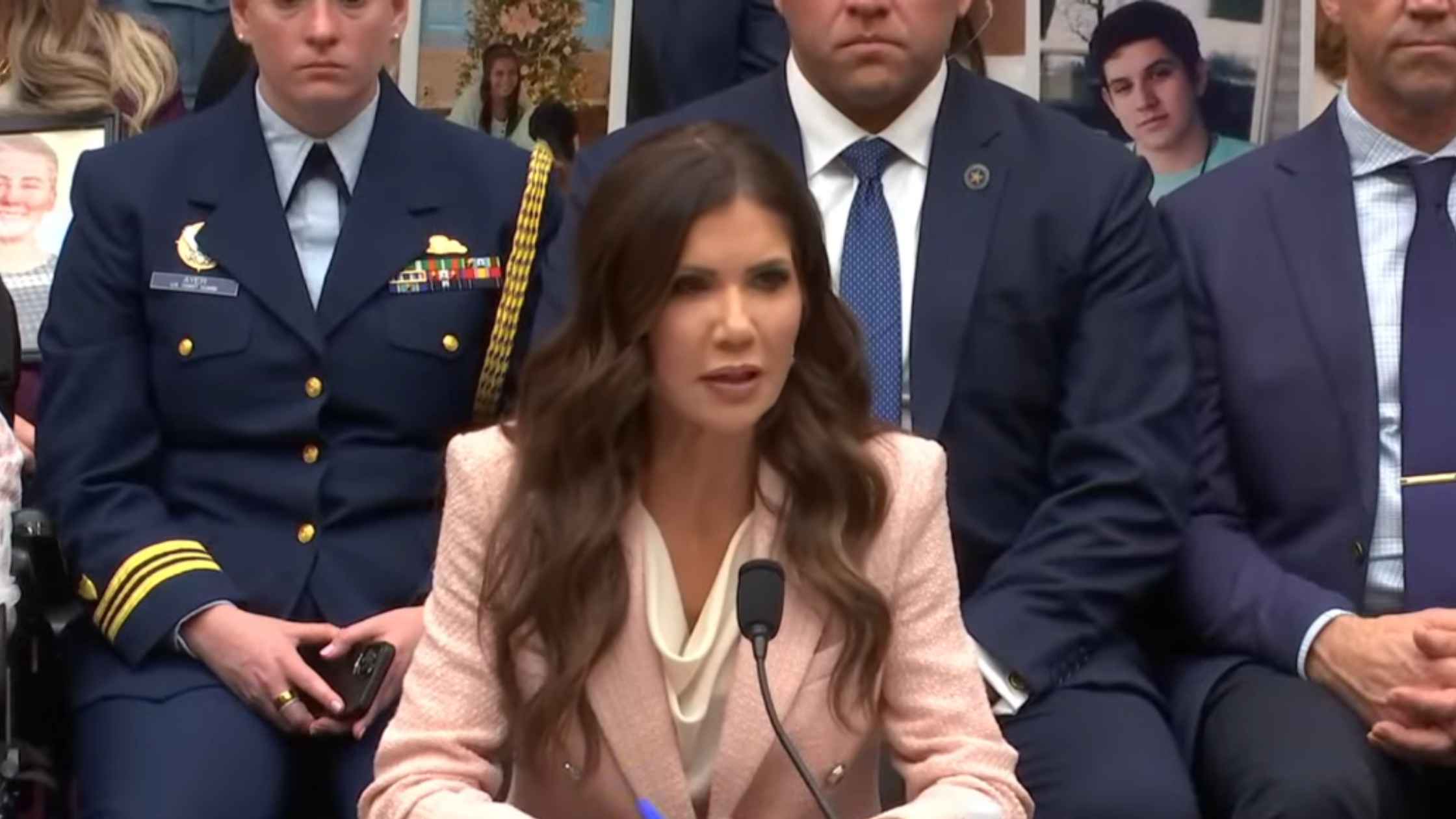

DHS Oversight Hearings Day Two

Kristi Noem testifies on DHS oversight before House Judiciary Committee. Read the transcript here.

DHS Oversight Hearings Day One

Kristi Noem testifies on DHS oversight before Senate Judiciary Committee. Read the transcript here.

Karoline Leavitt White House Press Briefing on 3/04/26

Karoline Leavitt holds the White House Press Briefing for 3/04/26. Read the transcript here.

Hillary Clinton's Deposition in Epstein Investigation

Hillary Clinton testifies about convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. Read the transcript here.

Bill Clinton's Deposition in Epstein Investigation

Former President Bill Clinton testifies about convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. Read the transcript here.

German Chancellor Friedrich Merz At White House

Donald Trump hosts German Chancellor Friedrich Merz at the White House. Read the transcript here.

Melania Trump Chairs United Nations Meeting

First Lady Melania Trump assumes the Security Council Presidency for a United Nations Security Council meeting. Read the transcript here.

UK Prime Minister Starmer Speaks on Iran Conflict

British Prime Minister Keir Starmer makes a statement in the House of Commons about the ongoing situation in Iran. Read the transcript here.

Medal of Honor Ceremony

Donald Trump speaks at a Medal of Honor ceremony at the White House. Read the transcript here.

Subscribe to The Rev Blog

Sign up to get Rev content delivered straight to your inbox.