Rev’s Transcript Library

Explore our extensive collection of free transcripts from political figures and public events. Journalists, students, researchers, and the general public can explore transcripts of speeches, debates, congressional hearings, press conferences, interviews, podcasts, and more.

Trump Gives Iran Update

Donald Trump holds a news conference to answer questions about Iran. Read the transcript here.

Vance Speaks to Firefighters

J.D. Vance addresses the International Association of Firefighters. Read the transcript here.

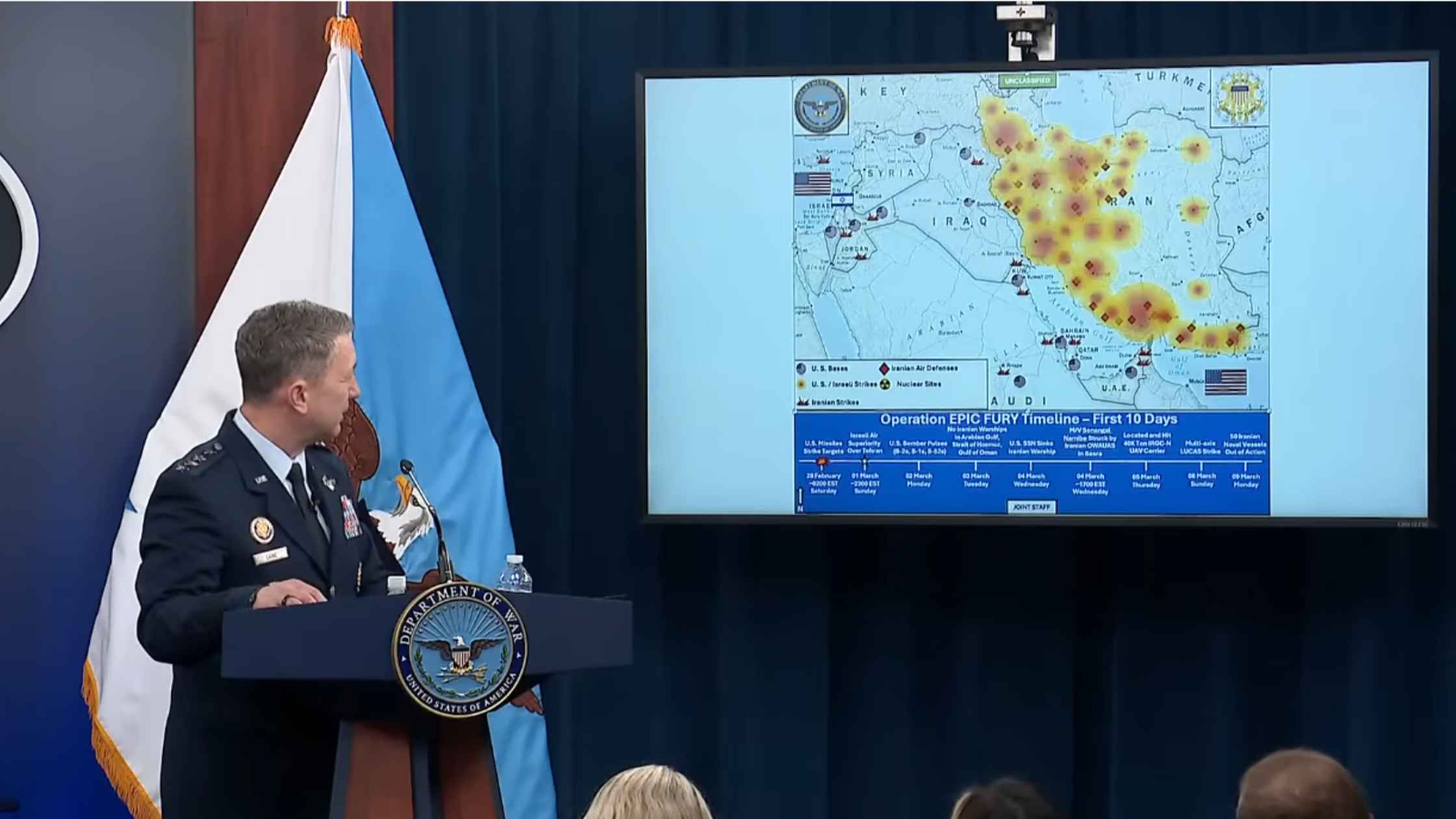

Iran War Update 3/10/26

U.S. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Dan Caine hold a briefing on Iran. Read the transcript here.

Republican Policy Retreat

Donald Trump addresses House Republicans at annual policy retreat in Florida. Read the transcript here.

Mamdani Press Conference after Protesters Attacked

New York City mayor Zohran Mamdani holds a news conference after bombs were thrown at protesters. Read the transcript here.

Hegseth 60 Minutes Interview

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth speaks with 60 Minutes news correspondent Major Garrett on 3/06/26. Read the transcript here.

Nutrition Education Announcement

RFK Jr. and Linda McMahon announce medical school commitment to nutrition education. Read the transcript here.

Jesse Jackson Memorial Service

Memorial service for the late Reverend Jesse Jackson Sr. in Chicago. Read the transcript here.

Hegseth Briefing at US Central Command

U.S. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth holds a briefing at U.S. Central Command. Read the transcript here.

Subscribe to The Rev Blog

Sign up to get Rev content delivered straight to your inbox.