Rev’s Transcript Library

Explore our extensive collection of free transcripts from political figures and public events. Journalists, students, researchers, and the general public can explore transcripts of speeches, debates, congressional hearings, press conferences, interviews, podcasts, and more.

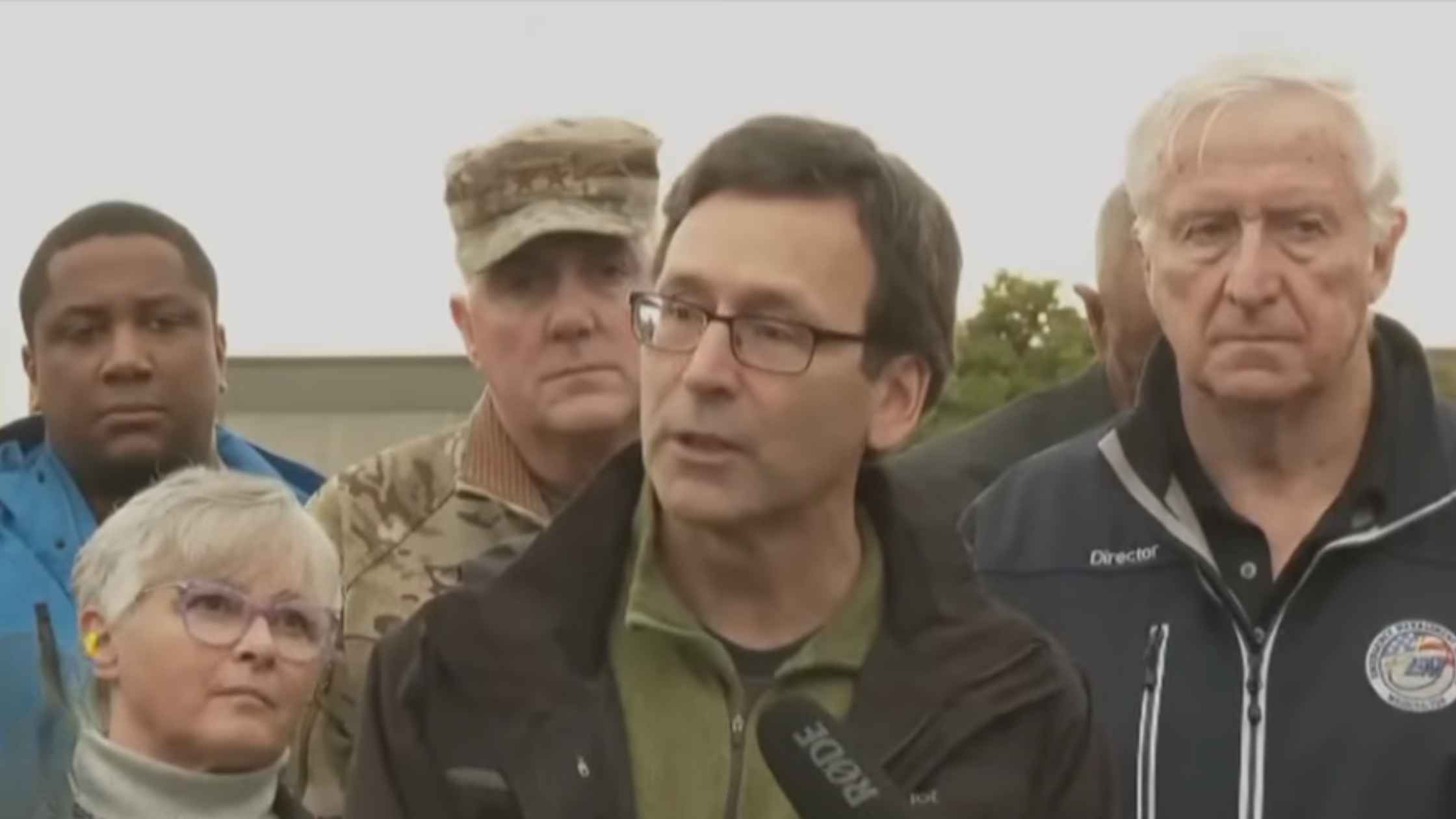

Washington Flood Update

Washington Governor Bob Ferguson provides an update on the state's response to flooding as heavy rains drench the Pacific Northwest. Read the transcript here.

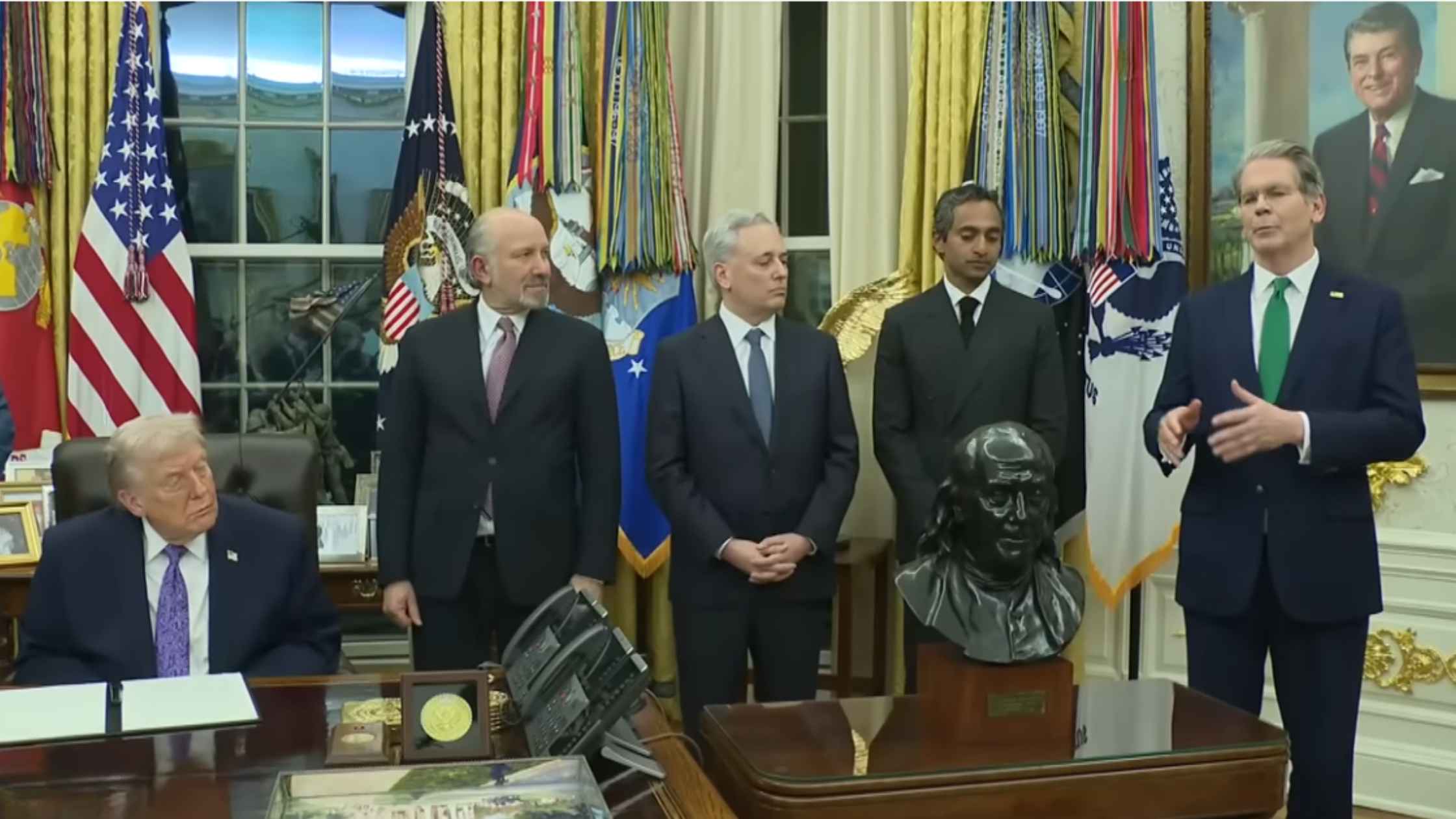

AI Executive Order

Donald Trump signs an executive order to override AI regulations by the states. Read the transcript here.

Homeland Security Hearing 12/11/25

Kristi Noem testifies on global security threats to the U.S. in a House hearing on Homeland Security. Read the transcript here.

Karoline Leavitt White House Press Briefing on 12/11/25

Karoline Leavitt holds the White House Press Briefing for 12/11/25. Read the transcript here.

Kilmar Abrego Garcia Released from Detention

Kilmar Abrego Garcia and supporters speak outside of an ICE detention facility after his release. Read the transcript here.

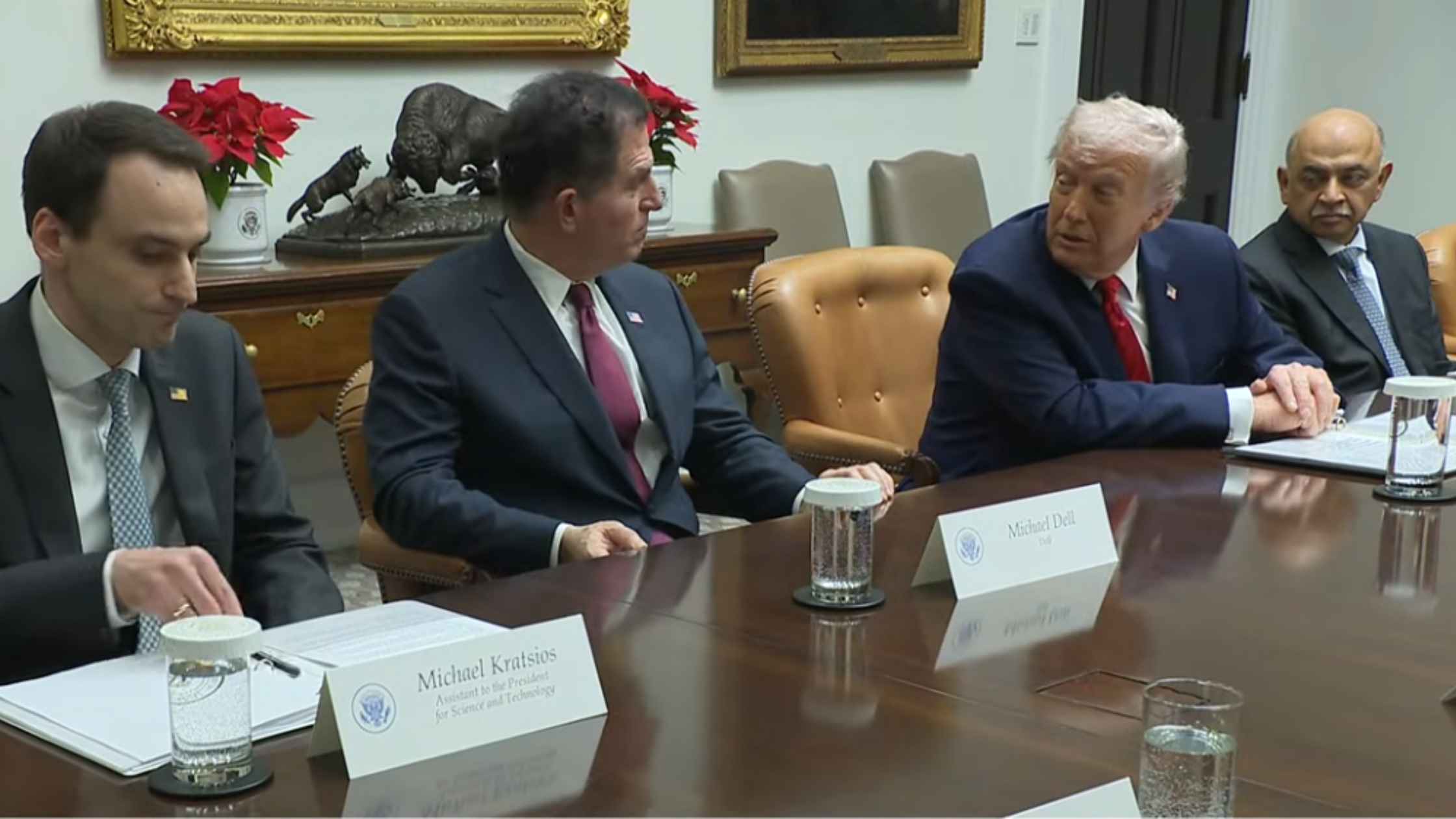

White House Technology Roundtable

Donald Trump holds a roundtable with business executives from top technology companies. Read the transcript here.

Nobel Winner Maria Corina Machado Holds Press Conference

Venezuelan opposition leader Maria Corina Machado holds a press conference the day after being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Read the transcript here.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell Speaks After Rate Cut

Jerome Powell holds a briefing after the Federal Reserve cut interest rates in another divided vote. Read the transcript here.

Airport Upgrade Campaign

Sean Duffy and RFK Jr. launch a new family-friendly travel campaign to upgrade airports. Read the transcript here.

Subscribe to The Rev Blog

Sign up to get Rev content delivered straight to your inbox.