Rev’s Transcript Library

Explore our extensive collection of free transcripts from political figures and public events. Journalists, students, researchers, and the general public can explore transcripts of speeches, debates, congressional hearings, press conferences, interviews, podcasts, and more.

Minneapolis Mayor on ICE Drawdown

Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey addresses the end of Operation Metro Surge. Read the transcript here.

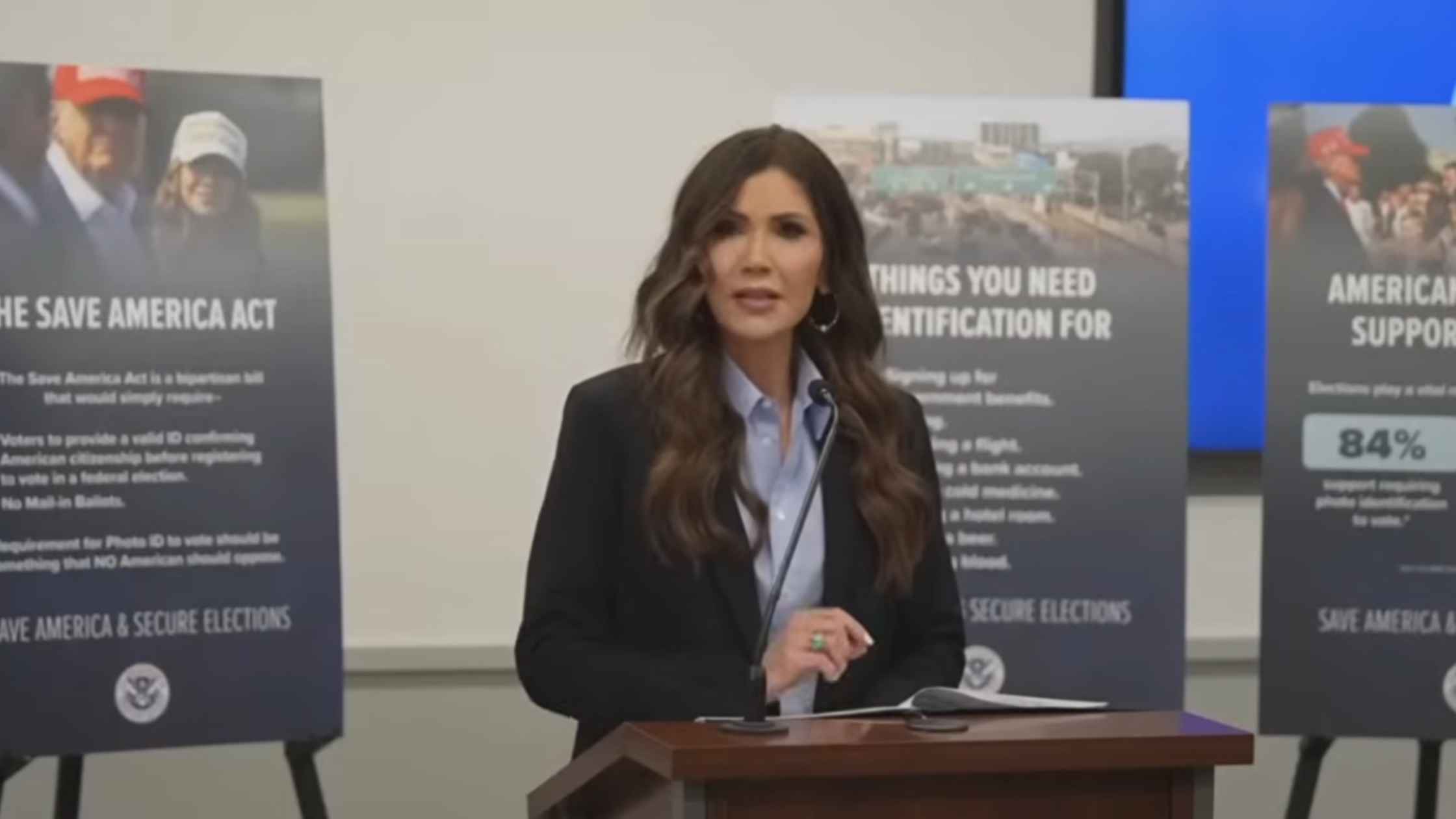

Noem on Elections

DHS Secretary Kristi Noem holds a news conference on election security ahead of the 2026 midterms. Read the transcript here.

Operation Metro Surge Ends

Border Czar Tom Homan announces the end of the federal immigration enforcement operation in Minnesota. Read the transcript here.

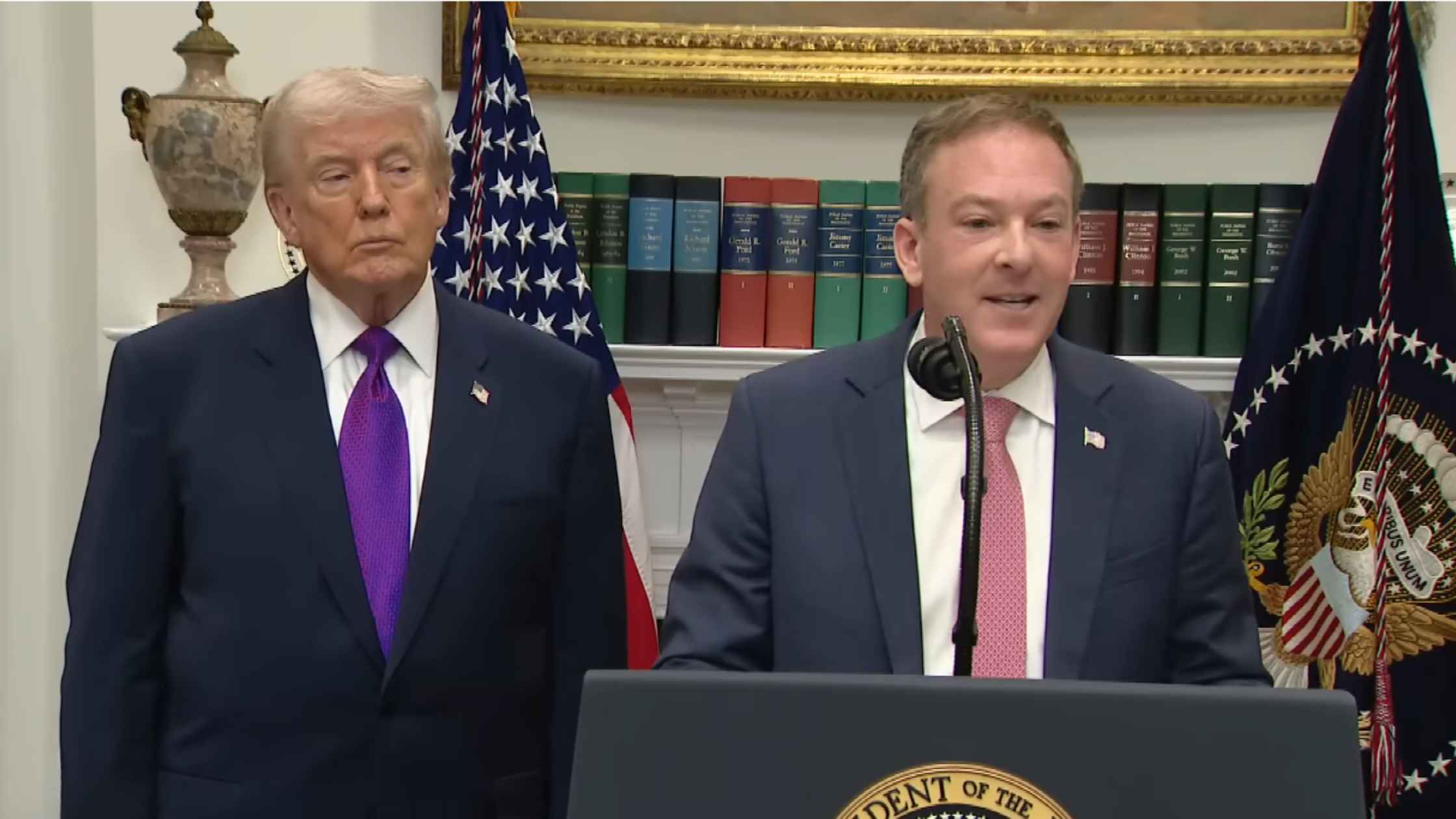

EPA Deregulation Announcement

Donald Trump and Lee Zeldin announce the end of the scientific basis for U.S. action on climate change. Read the transcript here.

Bondi Testimony Part Two

Pam Bondi appears at the House Judiciary Committee hearing on Justice Department oversight part two. Read the transcript here.

Bondi Testimony Part One

Pam Bondi appears at the House Judiciary Committee hearing on Justice Department oversight part one. Read the transcript here.

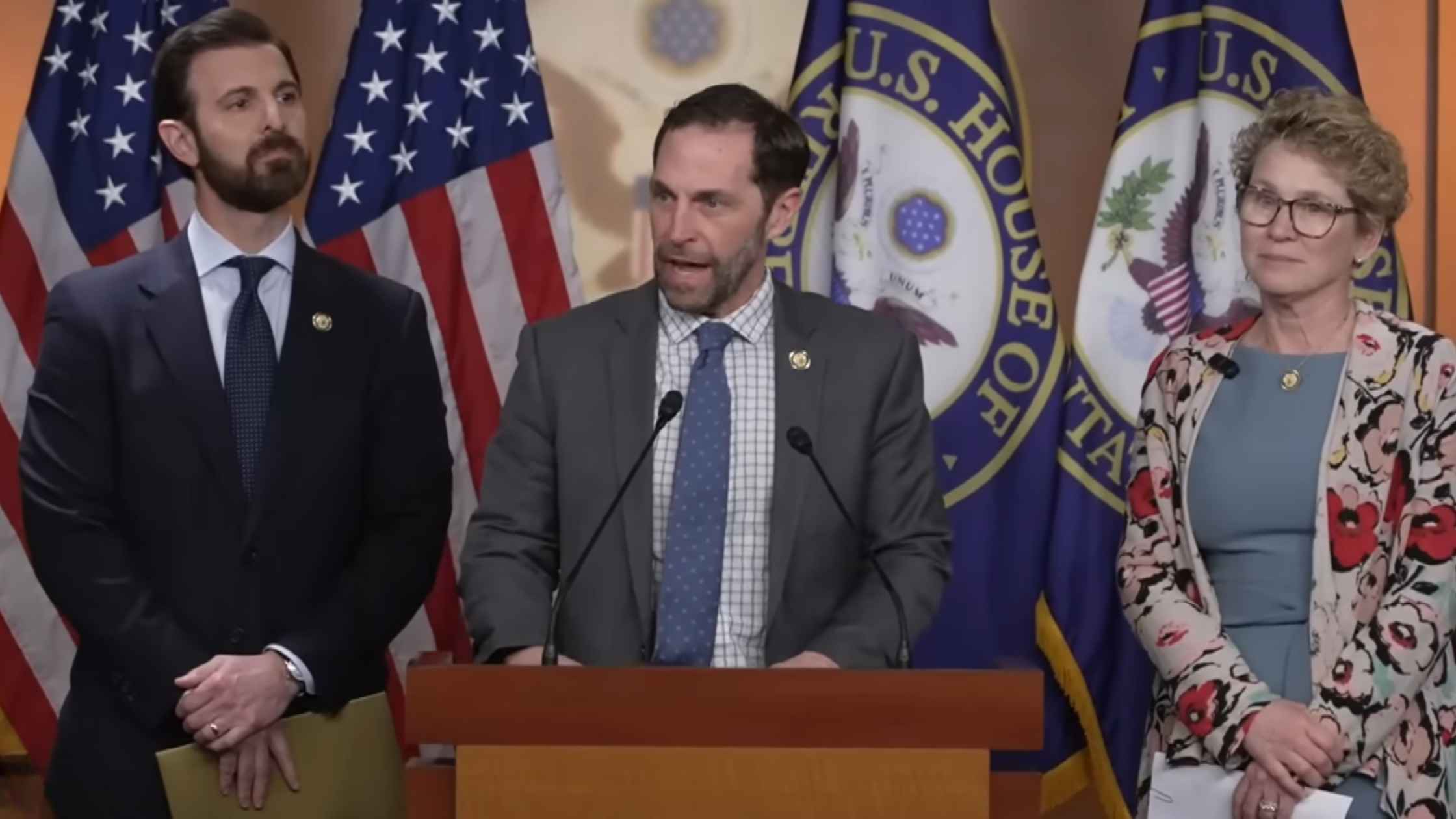

Illegal Orders Press Conference

Democrats speak after the "Illegal Orders" case is dropped by a grand jury. Read the transcript here.

White House Coal Ceremony

Donald Trump is dubbed 'Undisputed Champion of Coal' by a lobbying group at the White House. Read the transcript here.

Arctic Frost Congressional Testimony

Telecom executives testify before the Judiciary Committee on Arctic Frost. Read the transcript here.

Subscribe to The Rev Blog

Sign up to get Rev content delivered straight to your inbox.