Rev’s Transcript Library

Explore our extensive collection of free transcripts from political figures and public events. Journalists, students, researchers, and the general public can explore transcripts of speeches, debates, congressional hearings, press conferences, interviews, podcasts, and more.

Bondi Testimony Part Two

Pam Bondi appears at the House Judiciary Committee hearing on Justice Department oversight part two. Read the transcript here.

Bondi Testimony Part One

Pam Bondi appears at the House Judiciary Committee hearing on Justice Department oversight part one. Read the transcript here.

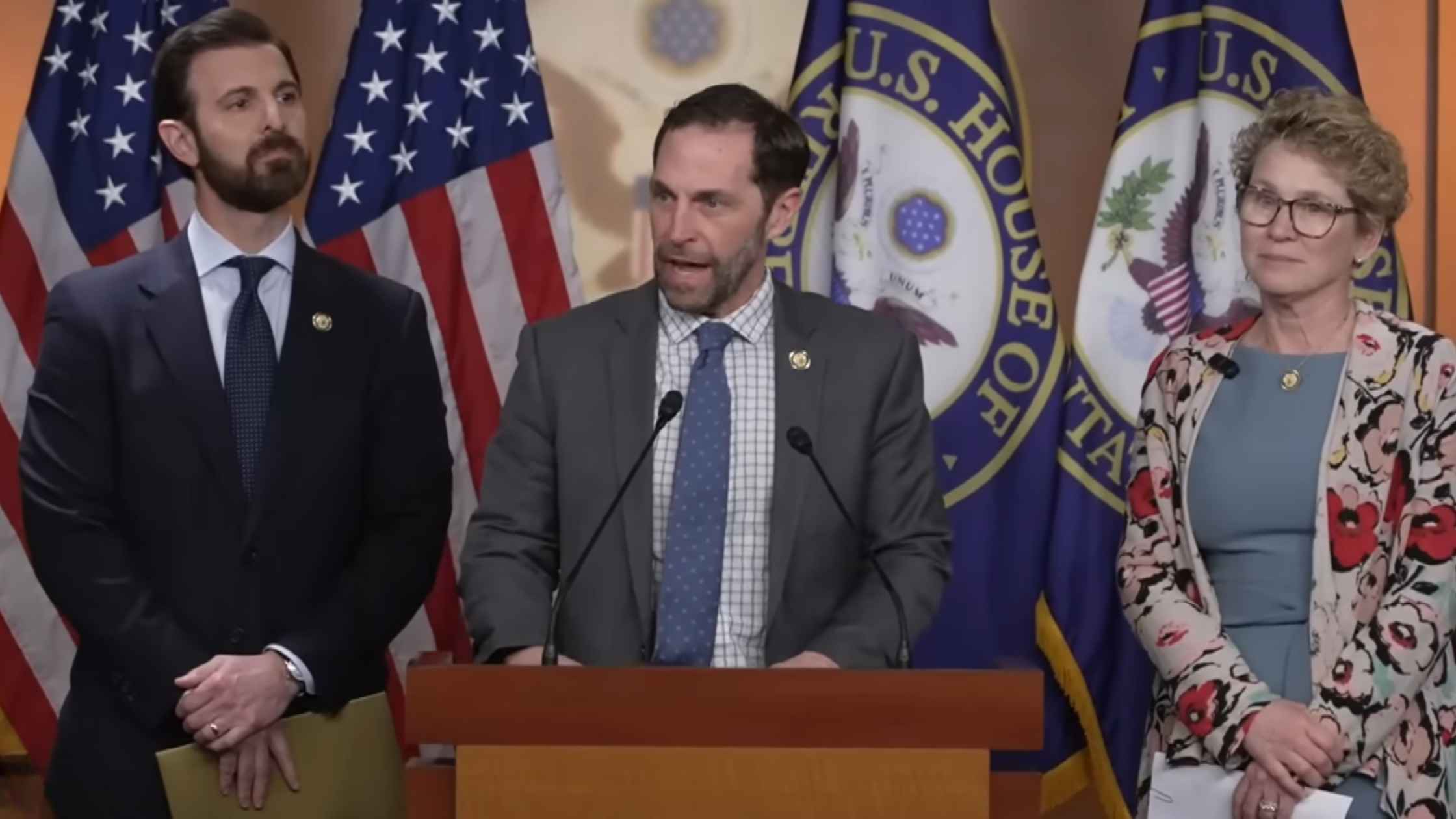

Illegal Orders Press Conference

Democrats speak after the "Illegal Orders" case is dropped by a grand jury. Read the transcript here.

White House Coal Ceremony

Donald Trump is dubbed 'Undisputed Champion of Coal' by a lobbying group at the White House. Read the transcript here.

Arctic Frost Congressional Testimony

Telecom executives testify before the Judiciary Committee on Arctic Frost. Read the transcript here.

Karoline Leavitt White House Press Briefing on 2/10/26

Karoline Leavitt holds the White House Press Briefing for 2/10/26. Read the transcript here.

Epstein Survivors Press Conference

Epstein survivors and lawmakers hold a news conference. Read the transcript here.

Lutnick Congressional Testimony

Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick testifies before the Senate Appropriations Committee. Read the transcript here.

Hegseth at Bath Iron Works

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth speaks at Bath Iron Works. Read the transcript here.

Subscribe to The Rev Blog

Sign up to get Rev content delivered straight to your inbox.